29: “Thursday, September 22, 1966”

Normally, the drive to Louisville would have taken a day and a half. But with the world’s time effectively stopped, the road was often jammed by motionless cars in every lane, so that Conrad frequently had to pull onto the shoulder to get around the photo-finish speedsters. The tunnels on the Pennsylvania Turnpike were particularly tough. Some cars simply had to be pat-patted out of the way. Two or three times, Audrey and Conrad walked into a motel, took a key to an empty room, and got some sleep. With all this, the trip took something like four days.

Of course, really, there was no telling just how long it took. Neither Conrad nor Audrey was wearing a watch, and the sun, stuck in the old timestream, forever hung there in its near-noon, September 22, position.

They ran into a rainstorm west of Pittsburgh, which was interesting. Each raindrop that hit their car would join their timestream and slide down to the road. Looking back, they could see a carved-out tunnel through the rain. It was interesting, but Conrad couldn’t figure out how to put up the convertible roof, and they were getting wet. So they stopped at a Howard Johnson’s, took the keys from the hand of a man about to unlock his Corvette, and proceeded in even better style.

The ease of taking the man’s keys gave Conrad the notion of robbing a bank, but Audrey talked him out of it. The trip was dragging on longer than they’d imagined, and it was all getting kind of spooky. It was on the last leg—from Cincinnati to Louisville—that it really started to get strange.

They were weaving along from lane to lane—every now and then skidding out onto the shoulder. Conrad was driving, and Audrey was staring out the open car window.

“Is it always so hazy in Kentucky?” Audrey asked.

“Hazy…” Conrad realized he’d been squinting for the last couple of hours. Things were getting harder and harder to see. It was like wearing the wrong pair of glasses.

“And look at the sun, Conrad, it’s gotten all fuzzy!”

Indeed the sun was fuzzy, and the landscape hazy. The great tapestry of past reality was beginning to fade.

“That’s not normal, is it, Conrad?”

“Normal! None of this is normal.” He tried to drive a little faster. Pass a car in his lane, dodge a truck in the other lane, skid around a solid block of three cars either way.

“We’re getting too far away from the main timestream, Conrad! That’s why the world is getting so vague. It’s out of focus!”

It got worse and worse—soon nothing was clear beyond a fifty-yard radius around the Corvette. It was like driving through thick fog—with the difference that the fog was bright, not dark.

“I’m scared, Conrad.”

“Maybe I should let you go. I could put you out by the roadside, and you’d leave my timestream. You’d be out there with all the regular people.”

“But it’s you I want, Conrad.”

“Well, hang on then, Audrey. Once I get that crystal we’ll see the flamers, and maybe they’ll help me out.”

Fortunately, Conrad remembered Louisville’s roads well, and they were able to find their way to Skelton’s. They pulled up his driveway, and the sun-hazed farmhouse reared up before them like a haystack by Monet. Hand in hand, they left the now-shimmering car and mounted Skelton’s steps. At the touch of Conrad’s feet, the steps grew satisfyingly solid.

They found Skelton on his back porch, poised over a trout fly in a vise. He was busy wrapping it with yellow thread. Like everything else now, Skelton had the gauzy outlines of an Impressionist painting. Conrad laid his hand on the old man’s shoulder. It took him a moment to get fully solid, and then he looked up.

“Conrad! How’d you sneak in like that, boy?”

“I’m outside of normal time. I just pulled you into my timestream. This here’s Audrey Hayes, who I’m engaged to. Audrey, this is Mr. Skelton.”

“Pleased to meet you, Audrey. Engaged to the saucer-alien, hey? Well, I suppose he can have kids like anyone else.”

“This is the first time I’ve heard we’re engaged,” said Audrey, smiling. “Conrad and I came here to see if you still had that crystal.”

“That crystal!” exclaimed Skelton. “If you only knew, Conrad, how the feds have been pestering me. Of course I never even allowed as how I had it back, but they would keep poking around. Yes, sir. I’ve got that crystal hid, and I’ve got it hid good.”

“Well, can I have it?”

“Yes… if you let me watch you use it. You know how much it would tickle me to see another saucer, Conrad, and—”

“No problem. And the sooner, the better. You notice how hazy everything is getting, Mr. Skelton? If my timestream gets too far off of the old reality, there’s no telling where we’ll end up. I want to get that crystal and call the flame-people for help.”

“Okey-doke. The crystal’s hid out in the smokehouse. I wedged her on into one of my country hams. It was my rolling the hams in rock salt that gave me the idea. It seemed fitting, what with you being made of pigmeat and all in the first place, Conrad.”

“Pigmeat?” exclaimed Audrey.

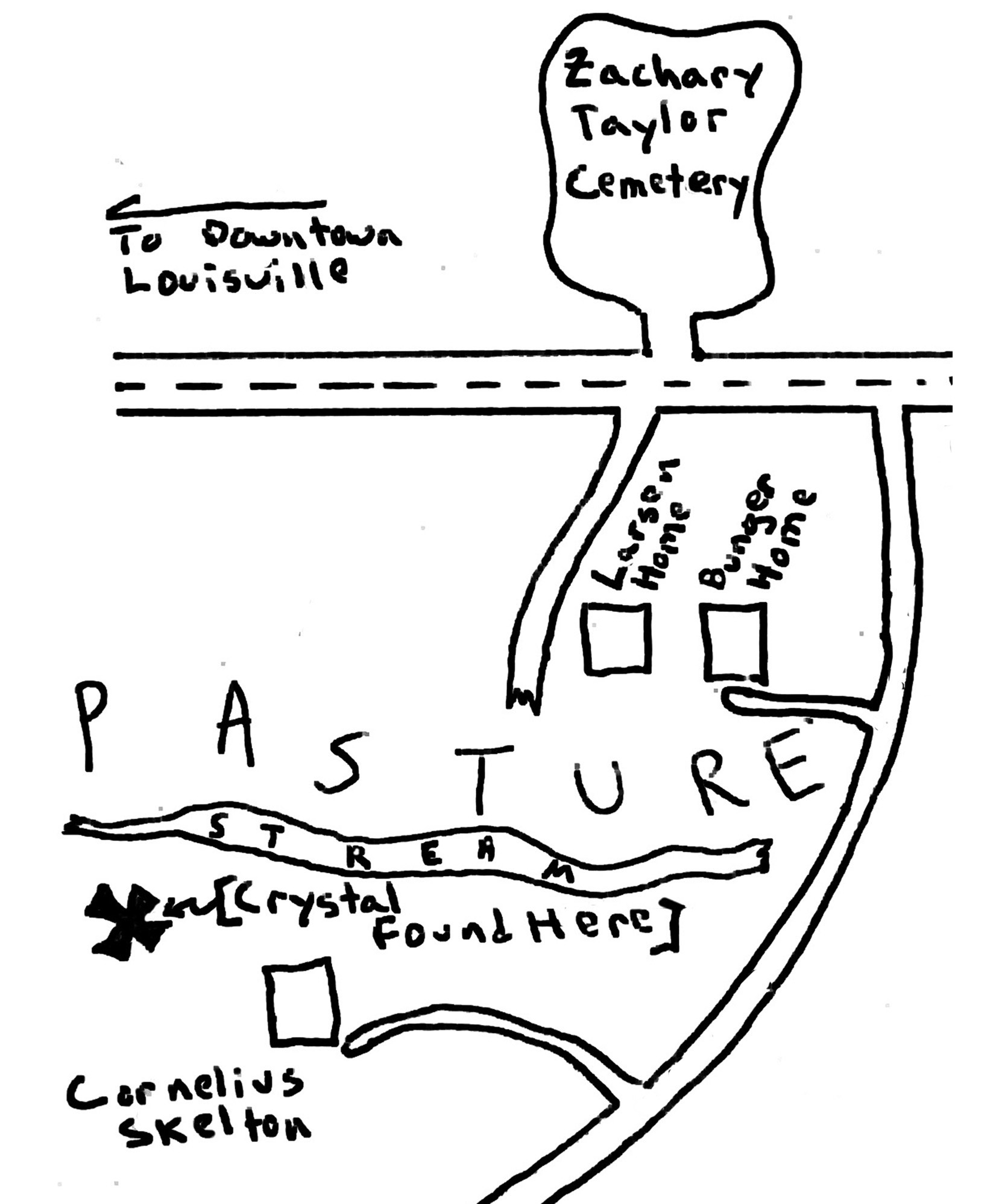

“Didn’t tell you that did he, hey?” chuckled Skelton. “Yep, that’s how Conrad got here. He was a stick of light attached to that crystal. When his saucer landed, he flew on out, stabbed his light into my prize hog Chester, doctored that pigmeat into human form, and walked off to join the Bungers. March 22, 1956. I saw the lights, but all I found was the crystal. Here we are.”

The three of them stepped into Skelton’s old stone smokehouse. Conrad kept one hand on each of his companions, pulling them along in his timestream. The smokehouse had the good familiar smell of fat and hickory. Skelton fumbled at one of the hams till he got it off its hook.

“Let’s go outside where there’s some light.”

They went out and sat down on the grass. The ham was in the middle, and the three people sat around it. The haziness had gotten so great now that everything outside of a small circle around them was gone. No house, no smokehouse, no sun, and no sky. Just raw color, lively specks of scintillating brightness.

Skelton felt around under the ham’s outer hide for what seemed quite a long time. Finally he drew out the crystal, shiny and glistening with fat. It was considerably smaller than the last time Conrad had seen it.

“Here, Conrad. You hold it, and I’ll keep my hand on you.”

The crystal tingled in Conrad’s palm. Where earlier it had been big as a matchbox, now it was no larger than a sugar cube. Even so, it nestled into the curves of his palm in the same tight way it had done back in the Zachary Taylor cemetery.

“This may take a few minutes,” said Conrad. “Let’s just sit tight.” He closed his eyes and concentrated. He could feel his memory pattern flowing down through the crystal and into the subether transmission channel.

“Now, why did you say the world’s so blurred?” Skelton asked Audrey. “I had a cousin who had glaucoma—the way he told it, glaucoma makes things look something like this. What did you say was the reason?”

“It’s because we’re on another timestream,” said Audrey. “We’re moving farther and farther away from the old world. Like taking a wrong fork in the road.”

The crystal was hot in Conrad’s hand; and his ears were filled with buzzing. Closer. Closer.

Mr. Skelton was getting nervous and impatient. “I sure don’t like having the real world drift away from us like this. If that saucer doesn’t show up soon, I’ve got a mind to…”

ZZZZUUUUUHHHUUUUUssss.

Five bright red lights solidified out of the bright haze, coming into focus as they approached. It was a square-based pyramid, two or three meters on a side. Still buzzing, it hovered closer, then touched down on the grass next to Conrad and the two humans.

For a moment the vehicle sat there like a large tent, and then one of its faces split open. Out came a stick of light with a gleaming parallelepiped crystal at one end. Remembering the fight in the graveyard, Conrad tensed himself for battle. He raised his own crystal up to the nape of his neck and got ready to unsheathe his stick of light.

But instead of attacking, the creature slid its flame into the big country ham that lay inside the circle of Conrad, Skelton, and Audrey. The flame-person’s crystal stayed outside the ham, stuck to its narrow end. The wrinkles in the ham’s skin formed themselves into a facelike pattern, and small feet seemed to stick out from the joint’s wide end. Now the leg of pork got up and made a little bow to Conrad. Conrad returned the bow, not knowing whether to be frightened or amused.

“Hello,” said the ham. “I see you are on your fourth power. We weren’t sure you’d be able to take it this far.” It spoke in a precise, hammy tenor.

“Where’s your-all’s home star?” demanded Mr. Skelton.

“We don’t have one,” said the ham. “We aren’t material beings. The whole stars-and-planets concept is relative to the material condition. I think there’s a human science called quantum mechanics that could express where we come from. Hilbert space? The problem is that none of us knows quantum mechanics!” The ham laughed sharply. “That’s one of the things Conrad was supposed to find out about while looking for the ‘secret of life.’” The ham laughed again, not quite pleasantly. “I must say, Conrad, some of your information is valuable, but on the whole—”

“Well, he’s only just starting,” said Audrey protectively. “I’m sure that sooner or later Conrad can learn everything on Earth that you flame-people want to know.”

“You’re Audrey,” said the ham knowingly. “Conrad’s girlfriend. Of course you stick up for him.”

“How do you know about me?”

“See that crystal Conrad’s holding?” asked the ham. “Besides being a power source, it’s a memory transmitter. Every time Conrad touches it, we get copies of all his prior memories. You’re Audrey Hayes, and Conrad is in love with you.” The ham paused, bobbing in thought. “Love. Most interesting. It’s been a mess from the start, but in some ways this is one of the most interesting investigations we’ve done. It’s just a shame that—”

“Isn’t there some way we can undo it?” asked Conrad. “I know I’ve screwed up—all the humans have heard of us now, and they’re hunting for me. But isn’t there some last power I could use to undo it?”

“‘Fifth Chinese brother,’ you call it?” The ham smiled. “It’s no accident that you thought of that story. Yes, you could be the ‘fifth Chinese brother,’ Conrad. And you could, in a sense, live happily ever after. But…”

“But what?”

“It might deplete your energy too much. You see how small your crystal has gotten. It’s the energy source that keeps your flame going, you know. One more wish and there’ll be next to nothing left. No crystal, and your light will stop burning. It could turn into a kind of death sentence for you: live your seventy-odd years on some version of Earth, and then that’s it. If you come with me now, we can replenish your crystal and you’ll be sure of getting away. There’s plenty of other ‘planets’ to investigate, you know.”

Conrad squeezed Audrey’s hand. “I want to stay. I want to be a person, and I want to keep looking for the secret of life.”

“We knew you’d say that,” said the ham. “That’s why we picked you in the first place. But I had to ask.” Pompously the ham bowed once again and laid itself back on the ground. The wrinkled features began to fade.

“Wait,” cried Conrad. “What do I do? How do I make the humans stop hunting me? What is the fifth Chinese brother?”

“You know where you want to be,” said the ham, its voice muffled and indistinct. “Just go there!”

Then the light-sword slid back out of the meat. The flame-person waved at them in a last salute, and then it whisked back into its scout ship.

ssssUUUUUHHHUUUUUZZZZ.

The red lights faded off into the unfocused blur that surrounded them. “What’s going to happen if I try to tell people my ham talked to me?” said Skelton after a moment. “Not even UFO Monthly would print a story like that! But you could do a great article, Conrad. Come on out and turn yourself in… hell, they’d let you go soon enough, and—”

“All that’s what I have to get away from,” said Conrad. “I’m not going back to that reality. Didn’t you understand what the ham said? I can pick the reality I want and go there. Here like this with everything out of focus, we’re nowhere in particular. Audrey and I are going to imagine our world all right again, and go there.”

“I liked my world fine the way it was,” groused Skelton. “I don’t want to forget all this, Conrad.”

“Fine,” said Conrad. “Just take your hand off me, Mr. Skelton, and you’ll go back to the old timestream.”

The old man hesitated a moment. “OK,” he said finally. “I believe I will. It’s been a pleasure, Conrad. Nice to meet you, Audrey. I’ll write an article explaining how you all disappeared.”

“Thanks for everything,” said Conrad. “And be sure to tell Hank Larsen that I came back.” Old Skelton nodded and drew his hand away. He froze into stillness and then, slowly, slowly, he dissolved into light.

“Let’s head off that way,” suggested Audrey, pointing out toward where Skelton’s lawn had been.

“OK,” said Conrad. “Here, take my hand like this… we’ll squeeze the crystal in between the two of us.”

“And think of where we want to be.”

“How about Crum meadow?”

“Yes. And you’re starting senior year, Conrad, and everyone’s forgotten about the flame-people and all that.”

“Yes. You’ve come down to visit… it’s Friday afternoon.”

“And Ace is going to let us use the room.”

“I’ll ask you to marry me.”

“You will? So soon?”

As they walked, the haze shifted here and tightened there. Before long it was the Crum, and everything was just the way they’d wanted. They had no memory that it had ever been any other way.

“Audrey?”

“Yes, Conrad?”

“Have you guessed yet what’s in between our hands?”

“Oh, will you finally let me see?”

“Go ahead!”

Audrey drew back her hand and found that Conrad had given her a diamond ring. The diamond was tiny, but very bright.