Alphabet Island

by Jessy Randall

OneMind Report 65-G

To: Lieutenant Marjorie Wells

Re.: Alphabet Island Project

As you know, something has gone awry with experiment #589, “Alphabet Island.” This report represents my understanding of events. Its purpose is not to lay blame, although I could do that too, easily. If such action is required, I would be more than happy to submit a separate, confidential report.

And please note: if you have received conflicting reports on this matter from my colleagues, I could meet with you in person to explain reality and smooth out any wrinkles or discrepancies. I am quite sure that I, more than any other linguo-scientist involved, am capable of being objective and not allowing emotion to cloud my judgment. Similarly, I trust that our close personal friendship and the close personal friendship of our parents will not affect your ability to be fair.

Now then. First facts. Experiment #589 called for the isolation of 20 to 30 human specimens age 2 to 5 on an island of undisclosed location in the South Pacific, along with three adults. The children were not to have any reading or writing skills upon commencement of the experiment, and indeed, we chose specimens who were, to say the least, not the brightest bulbs in the swimming pool, if you know what I mean. I mean these kids were not going to grow up to attend Oxbridge or Harvale, if you know what I mean, and I’m sure you do since you and I both attended one of these institutions and know that there is a sort who get in and a sort who emphatically do not.

Anyhow, they were orphans of course, pulled from child-farms all over the world, no more than one from any institution so that there would be no pre-organization into cliques, friendships, or indeed relationships of any kind. As in all experiments funded by OneMind, we made sure to avoid regional bias and corrected for racial prejudice. The children were all treated equally by the adults – I made sure of this myself.

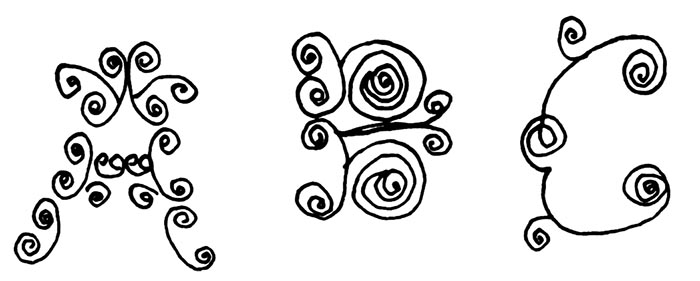

The main purpose of experiment #589 being to study the incremental simplification of the Roman alphabet in microcosm, we began by training the three adults involved (Janey, Satchway, and Proghouth) in a bizarrely curlicued form of the ABCs, example forthwith:

Translation: A B C D E F.

The adults (or “teachers” – we found this antiquated word useful during the process of the experiment) became adept at reading and writing in this alphabet, which came to be known as Curl, after about one month of intense practical immersion. My colleagues and I created several picture books and newspapers in the curlicue alphabet to be strewn in tatters around the island, and even made up t-shirts for some of the teachers and children spelling out amusing slogans in Curl.

We allowed the teachers two full years with the children and then, over the course of six months, caused them to “die” – a conceit in the case of Janey and Proghouth, although not, sad to say, in the case of Satchway, who succumbed to a form of malaria not seen in decades, and this report is of course dedicated to her memory, as should be all the reports you may receive on experiment #589.

The children, then aged 4 to 7, were left with ample writing materials, and we planned to observe them (using satellite technology and well-hidden jungle cameras) for twenty years further, to measure the rate of the simplification of Curl into the “normal” Roman alphabet used by the majority of civilizations in the world, i.e.:

A B C D E F

We were guided in our time estimations by the experiments of Urkhart, Smee, and Jones, who did similar work with Egyptian hieroglyphics, and by the linguo-scientist Filge, whose monograph on the tail of the letter Q we all found fascinating in graduate school. We expected simplification to be complete after twenty years, but if our expectations were wrong (you see, we were humble, we did not assume we knew everything in advance) we planned to keep the children isolated another ten years further, longer if the experiment required it, even into second and third generations.

Instead the experiment has ended after just five years after the teachers’ “deaths” and we are left with insufficient data, in my opinion, to draw any conclusion. But let us go in logical, chronological order, as we scientists (even linguo-scientists, who still do not get the respect we deserve) are wont to do.

In the first year that the children were left on their own, we saw no marked change in the curlicue alphabet. The children did not, in fact, seem interested in reading or writing at all, and they destroyed their Curl t-shirts for use as rags and ropes. The island was well-supplied with food and water, containing an adequate natural spring, banana trees, breadfruit, berries, coconuts, and other tropical delights. (Side note: we scientists were at times envious of the children, who had no duties and no wants – all was provided to them by nature. They also lived without many of the disruptive technologies of the present day: radio, video, the six-u, etcetera.) Nevertheless, they did not seem to use the alphabet for storytelling or even doodling in the sand; rather, they spent most of their time foraging for food, playing games of their own invention, sleeping, and at times blubbering to each other about the “dead” teachers.

We were patient. We did nothing to interrupt the experiment or change its results. Even when two of the children became ill from unknown causes (we think they attempted to eat a diseased seagull) we kept to our hands-off policy. Both children recovered almost fully.

During the next year, we believed our patience had paid off. The children began to use Curl to write down the story of their island, which had previously been told only orally around the proverbial campfire. We expected the simplification of Curl to begin promptly. What the children did, however, was wholly unexpected and, to say the least, quite maddening. They began adding curlicues to Curl, treating their alphabet as if its purpose was not communication, but decoration! Example follows:

Translation: A B C.

We waited for a turnaround. Surely, the children would see the error of this development. Writing a simple story could take hours, even days, with an over-curled alphabet. The story of the island took up four times as much space as it had previously. They ran out of the paper and writing utensils we had generously provided and began using papyrus leaves and burnt sticks. This made writing even more time-consuming, of course. We did not believe this state of affairs would last, and so again, despite a distinct sense of unease on my part (that I believe I conveyed to my wife, should you care to investigate), we kept our hands off the experiment.

This, I now believe, was the experiment’s fatal error. The children were left too long to their own devices. Now, in the last few years, they have developed a form of Curl that we linguo-scientists can not decode. It is indecipherable gibberish and in my opinion carries no meaning and is meant to be merely “art,” if teenagers can be considered “artists.” The letters no longer stand on their own, but blend together into what we call “letter-objects.” If the alphabet is still an alphabet (and not, as I believe, the scribbling of thankless malcontents), we have no choice but to believe the children have created a blend of alphabet and pictograph, with some letters encompassing others and entire sentences or even paragraphs built into each letter-object. Example follows:

Translation: unknown.

But I believe that if this design, or story, or whatever it is, has meaning, that it may contain something unflattering to myself and my colleagues. To be quite frank, I have a sinking feeling that the specimens – human children! – are laughing at us, using their worthless graphic invention for no higher purpose than unjust insult and mockery of those who have provided for them since infancy.

I may not speak for all my colleagues when I say this, but I believe it is time to pull the plug on Alphabet Island. The experiment has been an unqualified failure, on which we have wasted a great deal of money and from which we can learn absolutely nothing.

About the Author

Jessy Randall is the Curator of Special Collections at Colorado College. Her poems, humor pieces, and other things have appeared in Asimov’s, McSweeney’s, The Magazine of Speculative Poetry, and Star*Line. Her young adult novel The Wandora Unit (Ghost Road Press, 2009) is about love and friendship in the high school poetry crowd. She has a collection of collaborative poems, Interruptions, forthcoming from Pecan Grove and a solo collection, Injecting Dreams into Cows, forthcoming from Red Hen. She also blogs about library shenanigans.

Please mention the author or this piece's name in your comment.