Hieronymus Bosch's Apprentice

by Rudy Rucker

Once inside the town wall, Azaroth swung the boat into a little canal that wended its way through the town, passing under round-arched bridges and along back yards verdant with vegetables. Bosch’s house wasn’t far.

Azaroth moored his boat beside a tiny dinghy tied up by a garden. He put a likely offering of fish into a smaller basket, tossed a cloth over the remainder, then led Jayjay and Thuy through the garden of turnips and carrots, past a cellar door, and up three steps into Jeroen Bosch’s kitchen.

It was a large room, the ceiling and three of the walls covered with smooth white plaster. The inner brick wall held a fireplace adorned with stone carvings of skinny dogs with needle teeth and bat wings. The dogs’ long tails branched into curling ferns that held up a mantelpiece upon which a freshly roasted chicken cooled.

Dark-varnished planks of wood made up the floor. The ceiling was painted with an elaborately twining squash vine adorned with birds and beasties peeping from behind each flower and leaf. Counters and cupboards lined the walls, with a sturdy wooden table beside a window.

Two women sat at the table: a plump servant girl peeling carrots and turnips, and a lean, gray-haired woman wearing a white linen cap and a bright yellow silk dress. Her air of self-possession made it clear that she was Bosch’s wife and the lady of house.

“Good day, Mevrouw Aleid,” said Azaroth with a bow to her. “I have a fine fat fish for you, also a tasty eel. ” Thuy and Jayjay stood behind Azaroth, peeping out. He drew the dogfish from his basket and held it up. “And I’ve brought this fellow to model for the master.”

“That’s very good of you, Azaroth,” said Aleid, with a cool smile. “But we didn’t know you’d be delivering fish. We’ve already cooked for tonight.”

“Eat my catch tonight,” suggested Azaroth. “Have the chicken cold tomorrow.”

Just then Aleid’s eyes picked out Jayjay and Thuy. Abruptly she crossed herself. “Get the knife, Kathelijn!” she cried.

The red-cheeked young maid sprang to her feet, ran back towards the hearth and snatched up a long, skinny boning knife. Aleid, too, hastened to the far side of the room and turned, watching for a move from the strangers.

“These are just my cousins from the Garden of Eden,” said Azaroth nudging them into the open. “Jayjay and Thuy. Fortunately they speak good Brabants.”

“Pleased to meet you,” said Thuy in her sweetest Dutch. She even curtsied. Seeing this, Kathelijn lowered her knife and let out a shrill, nervous giggle.

“Perhaps Mijnheer Bosch would like to paint us,” said Jayjay. “Or we could assist in the studio or about the house. Being new to your beautiful town, we’re open for any position of service.”

“We should welcome dwarves?” said Aleid, incredulous. “Creation’s cast-offs?”

“We’re not dwarves,” said Jayjay firmly. “We’re little people, clever and strong. If you permit...” He stepped forward, grabbed one of the chairs’ legs with both hands, and lifted it into the air. Although the chair was three times his height, relative to his dense Lobrane body it felt like balsa wood, with a net weight no greater than a normal chair.

But the feat of strength only frightened the women. The fact that Jayjay and Thuy could move six times as fast as the Hibraners made them rather uncanny. Aleid found a knife of her own. Kathelijn crouched and pointed hers at Jayjay. He clattered the chair to the floor and backed away.

“Are you baptized?” asked Aleid, tapping the flat of her knife against her palm.

“I am,” said Jayjay, whose mother was a knee-jerk Catholic.

“Me too,” said Thuy, who’d had a brief Christian period in grade school, thanks to her born-again aunt.

“Has Jeroen finished painting my harp?” asked Azaroth, trying to turn the tide of the conversation.

“Go ask him yourself,” said Aleid. “Be warned that he’s in a bad mood. A beggar keeps playing his bagpipe right out front. Can you hear it?” Indeed, shrill, frantic squeals were filtering in. “We give him a copper to go away, and he always comes back for more. Show Jeroen the dogfish and the little people. They might very well amuse him.”

“We admire your husband’s paintings,” said Jayjay.

“You’re so cosmopolitan in the New World?” said Aleid, surprised. “I had no idea.” She paused, re-evaluating the situation. “Were my husband to want you to stay, you should know that you’d receive no pay. You would sleep in our cellar. It doesn’t actually connect to the house, there’s an entrance from the garden. It would be like your own apartment. And you could eat the scraps from our table—we don’t happen to own a pig just now. I don’t suppose you eat much.” Clearly Aleid was a tough negotiator.

“We eat as much a regular people,” said Thuy. “In fact, we’re hungry right now.”

“But we don’t eat brown bread,” added Jayjay, not ready for a repeat of the fierce hallucinations he’d had from eating ergot-tainted brown bread with the limbless beggars behind the Hospice of Saint Anthony last night.

“Neither do we,” said Aleid, undermining Jayjay’s half-formed theory about how Bosch was getting his visions. “We eat white bread,” she continued. “Brown bread is for the lower classes. Are you nobles?”

“In a way,” said Thuy. “We’re known far and wide in our home land.”

“Can I feed them some carrots?” Kathelijn asked Aleid, sweetening her voice. “They’re so cute. Like dolls.”

Aleid nodded, and the maid gave each of them a raw June carrot, crunchy and sweet.

“How about a couple of chicken legs, too,” said Jayjay. “We’re famished from the trip.”

Aleid raised her eyebrows, but gave Kathelijn the go-ahead. Jayjay and Thuy made short work of the big drumsticks. Relative to their dense Lobrane jaws, the meat was spongy and easy to wolf down. It tasted wonderful. The women laughed to see the little people eat so heartily and so fast. Then Kathelijn gave Thuy a white bakery roll the size of Thuy’s head, and she gobbled it down, provoking further expressions of wonder.

“Go see Jeroen,” reiterated Aleid when the eating was done.

Jayjay and Thuy followed Azaroth up a staircase to a sunny studio in the front of the house. As it happened, the windows gave directly onto the great triangular marketplace and its articulated hubbub. The room sounded with a hundred conversations, with vendor’s cries, the scuff of shoes and the clack of hooves—all this overlaid by the vile drone of an incompetently played bagpipe.

A cluttered work table sat in the middle of the studio, and beyond that was Jeroen Bosch, standing before the window, brush in hand, the light falling over his shoulder onto a large, square oak panel.

“Aha!” he exclaimed. “Azaroth brings fresh wonders.” His face was lined and quizzical; his eyes were brown with flecks of yellow and green. His mouth and eyebrows flickered with the shadows of his fleeting moods. He looked to be in his mid forties.

“These are my cousins, Jayjay and Thuy,” said Azaroth. “They’re from the Garden of Eden.”

Bosch tightened his lips, clearly doubting this.

“Your wife says they might stay here and work for you,” added Azaroth.

“What!”

Azaroth held up his hand. “We’ll talk about that in a minute. How goes the progress on my harp?” The instrument was nowhere to be seen.

Jayjay was looking around the studio, fascinated. The work table held seashells and eggshells, drawings of cripples, a bowl of gooseberries, a peacock feather in a cloudy glass jar, and a variety of dried gourds. Upon the wall were a cow skull and a lute. A stuffed heron and owl perched upon shelves. Two nearly completed paintings leaned against the wall, panels half the width of the big square that Bosch was working on, and easily four times Jayjay’s height. Each panel was a mottled microcosm, brimming with incident and life.

“I’m nearly done decorating the harp,” said Jeroen. “But she’s locked up in the attic. She’s too valuable to uncover with so many people about.” He made a gesture towards the bustling marketplace. “Conjurors, charlatans, jugglers.”

“I can’t see the harp?” said Azaroth, incredulous.

The painter set down his brush and walked over to them, keeping an eye on Jayjay and Thuy. He accepted the dogfish from Azaroth, set it on his work table and propped its mouth open with a porcupine quill. “Hello,” he said to the dogfish, making his voice thin. “Do you bring a message from the King of Hell?”

Bosch was playing—seeking inspiration by enacting a little scene that he might paint. To ingratiate himself, Jayjay responded as if speaking for the fish, flopping his tongue to make his words soft and slimy. “The pitchfork wants to strum the harp,” he said, nothing better popping into his head. “The harp and the pitchfork are God.” He reached out with is hand and waggled the fish’s gelatinous brown tail.

Bosch nodded, appreciating the mummery, if not taking the words seriously. He was studying the singular objects on his table, nudging them this way and that with the tip of his delicate, ochre-stained finger—as if composing a scene. “Would it be heresy to say all things have souls?” he said, suddenly fixing his eyes on Jayjay.

“Where I come from, it’s obvious that everything is alive,” said Jayjay, feeling a closeness to Bosch that was nearly telepathic. He slowed down his voice to seem less strange. “Nobody debates it. It’s a fact of nature, not an insult to God. We talk to our objects and they talk back. That shell there, it might be saying, ‘I’m spiral, and my inside chambers are private. I used to have a slippery mollusk inside me, but then a dogfish ate her. The air is eddying inside my empty mouth; it’s faster and thinner than water.’”

“Very plausible,” said Bosch, studying him. “And your name is Jayjay?” He said it like Yayay. Jayjay felt like nobody had ever seen him so clearly before. Slowly Bosch turned his omnivorous gaze upon Azaroth.

“The harp is most certainly alive,” said Bosch. “Perhaps she belonged to a fallen angel. I’d very much like to keep her.”

“If you kept her safe in your family, that would be fine,” said Jayjay.

Azaroth sharply cleared his throat, wanting to argue. Jayjay turned and addressed him in rapid English. “That’s how your aunt gets the harp in the first place!” he hissed. “Think it through. The harp is supposed to stay here and pass down through the generations so your aunt inherits her.”

“Um—maybe,” said Azaroth confused. “But I took my aunt’s harp away and brought it here. So if I leave it here and come back empty-handed she’ll—

“It has to happen this way,” insisted Jayjay. “We have to leave the harp. We’re in your past, dog. We have to make sure all the same things happen.”

“You don’t know my Aunt Gladax,” said Azaroth.

Bosch was looking back and forth from one to the other as they continued talking English.

“Here’s an upside,” said Jayjay. “If you give Bosch the harp, you can ask him for a favor. Ask him to hire Thuy and me. That way I get a chance to play the Lost Chord and unfurl lazy eight for the Hibrane! It’s all preordained.”

Azaroth glared at Jayjay for a moment, then looked over at Bosch. “You can keep the harp if you let my cousins stay with you,” he said in Dutch. “They need a home. They’re just as clever and strong as full-sized humans. They can help you in your studio and around the house.”

“You truly grant me the harp?” said Bosch, his face lighting up, wrinkles wreathing his eyes.

“She belongs with you,” said Azaroth, not liking this.

“I could make Jayjay an apprentice,” said Bosch. “My brother Goossen’s sons have no time for me these days. My piety disturbs them.” The bagpipe music droned on, just outside. “It would be useful to have someone cunning and nimble for certain jobs,” continued Bosch. “Like painting escutcheons on the columns in the cathedral, or decorating a house’s gables. Or painting over—” He squatted down, studying Jayjay with his lively eyes, the corners of his mouth in constant motion. “Would you like to paint something special for me, boy?”

“I would.”

“What about me?” said Thuy. “I’m the artistic one. I’m a writer.”

“I don’t want two gnomes in my studio,” said Bosch shaking his head. “I don’t want to live in the world that I paint.”

“I won’t leave,” said Thuy. “I’m Jayjay’s wedded wife.”

“Oh, they have all seven sacraments in the Garden of Eden?” said Bosch. “Unheard of news.” He cocked his head, staring at them. Bosch’s green and brown eyes understood, suffered, forgave, were amused. “Don’t imagine you can gull me. Where are you two from?”

“California,” said Jayjay. “Not Eden but, yes, it’s in the New World, so far west that it’s very nearly the Spice Islands, which is approximately where my wife’s parents were born.”

“The world grows apace,” said Bosch. “Were you married in the Church?”

“Married in City Hall,” said Jayjay. “That’s just as good in California. We worship our government.”

“Well, I suppose your Thuy can sleep here too. But she’ll have to busy herself elsewhere during the days. Suppose she leaves every morning, and only returns at suppertime or, better, later than that.”

“She can spend the days with me,” said Azaroth. “She’ll help with my fishing and I’ll show her around town.”

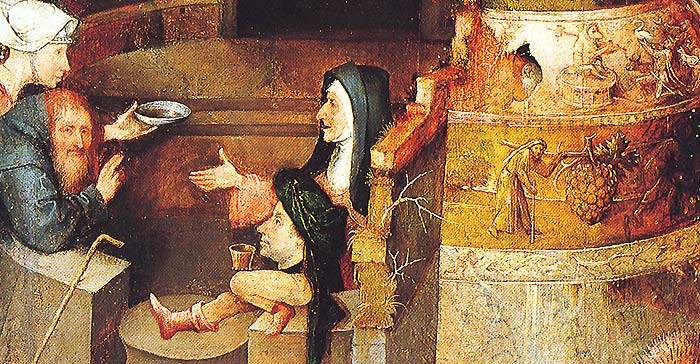

“That’ll do,” said Thuy. She was studying the tall paintings leaned against the walls. “Oh, wow. These are the wings of The Temptation of St. Anthony!”

“Indeed that’s the theme of this triptych,” said Bosch. “Very perceptive of you to read the iconography. Perhaps I’ll let you study my works in the mornings before you leave.”

“I recognized the panels, too,” Jayjay was quick to say. Thuy gave him the finger. But with a smile.

“Let’s go, Thuy,” said Azaroth. “We’ll take the rest of my catch to the fish market. And I’ll show you the tavern where I live. It’s an interesting place. Lots of vibby types in town for the annual procession. Musicians, actors, acrobats,”

“The Muddy Eel,” said Bosch, shaking his head. “Full of whores and dreadful music. Which reminds me—”

With no transition at all, the artist strode over to the room’s window and began screaming imprecations at the unseen man who was playing the bagpipe. The music broke off, and a tenor voice called up, wheedling for alms. Bosch cursed again; the squealing resumed.

“Do you want me to get rid of him, Jeroen?” said Jayjay. “I’ll show you how useful I can be.”

“Let it be so. And usher your two companions out the door.”

Jayjay and Thuy skipped down the stairs hand in hand, hopping from one step to the next, both of them very excited. The ground floor front room was full of painting supplies: oak panels, pots of pigment, a work bench for mixing paints, cupboards of rolled-up drawings. No apprentices were to be seen.

Jayjay, Thuy and Azaroth stepped out the front door. The pesky bagpiper sat at the base of the stone steps, the same unshaven man they’d seen on the road, now red-faced and smelling of wine. Surprised to see the two tiny figures emerging from Bosch’s house, he broke off his sonic assault. He wiped his ropy lips, then favored Jayjay with a sneer. But not for long.

Jayjay was on him like a sped-up goblin, pummeling him in the ribs and booting him in the butt. Surprised and yowling, the bagpiper limped away. Some of the bystanders booed, some cheered, and Bosch cackled from his window.

Jayjay bowed from the top step and announced himself. “I am the new apprentice of Jeroen Bosch!” He took Thuy’s hand. “And this is my wife. We offer you friendship; we require respect! Hurray for ‘s-Hertogenbosch!” Just to dispel any scent of the diabolic about the curious figures they cut, Jayjay—and then Thuy—slowly crossed themselves.

“I hope we didn’t do that backwards,” said Thuy, looking out at the crowd. “Oh, whew, they’re smiling. Way to go, Jayjay.”

Jayjay bid Thuy and Azaroth good-bye and hurried back to Bosch’s studio.

“I’m often guilty of the sin of anger,” the artist said pensively. He’d settled behind his painting once more; he was touching up the images of some tiny bas-reliefs depicted upon a temple pillar near Saint Anthony. “And I fall into pride over my work. I lust as well, though less so than in my youth. How about you?”

“I don’t see myself that way,” began Jayjay. “It’s—” But then he broke off. Bosch was regarding him with those profoundly knowing eyes. Why lie to him? “I guess you could call me a drunkard,” admitted Jayjay. “Of sorts.”

He was thinking of the wine and the ergot, not to mention the Big Pig trip he’d taken when he should have been honeymooning with Thuy. He’d spent most of his life trying to get high, and yesterday he’d ended up paralyzed in a diaper beside another guy having sex with his wife. And last night—this was the rich part—as soon as his paralysis had worn off, he’d gotten drunk with crippled beggars and had eaten the psychedelic that was making their fingers and legs drop off.

This was his actual life, the only life he had. He had a sudden sensation of standing on a ridge looking back at a valley devastated by years of strip-mining. His past.

“Gluttony,” said Bosch. “I see it now. You seek outside, instead of seeking within. You risk losing your soul and becoming an empty shell.”

“You’re a glutton for images,” said Jayjay defensively. He gestured at the extravagant fantasies on the panels against the wall: the fish like ships in the sky, the burning cities, the devils and nudes and chimerical beasts.

“I make these things from within myself,” said Bosch. “I don’t gobble and guzzle in search of bliss. God sees you, Jayjay. God is always watching.”

“That’s a stupid way to think,” snapped Jayjay, recoiling from his taste of self-knowledge.

“You’re the one who’s lost,” murmured Jeroen, focusing on the images he was painting. “You rail at the fog.” He touched his dry, narrow tongue to his lips as he worked.

“Why should I think of God hating me for every little thing?” demanded Jayjay. “My mother already did that. And my in-laws. And the preachers. And the government. God should be more than an angry eye in the sky. Maybe God isn’t what you think, Jeroen. Maybe God is that harp in your attic.”

Bosch paused, brush poised in the air. “It pleases you to be merry. I freely can agree that God is an unfathomable mystery. But the issue is your gluttony. Know that hell is the sinful life.”

“Nobody paints hell as well as you, Jerome,” said Jayjay, more than ready to change the subject. “It’s ironic how uninteresting heaven always looks.”

“Look closer,” said Bosch. “Sacred and ordinary things are strange monsters, too. All made of the same paint.”

Jayjay walked around to Bosch’s side and noticed a dissected stingray in the picture. Still fighting against the cathartic revelation Bosch was leading him towards, Jayjay shot a verbal jab:

“Did you torture animals when you were a boy?”

“Impudent imp! I was a timid lad. But often I watched the butchers at work. And I saw my brother Goossen’s friends stone a cat to death. Horrible. I fear cats. And so I paint them. Painting hell is heaven.” He pointed with the end of his brush at a toothy, squalling cat face on a demon near the kneeling Saint Anthony. Saint Anthony was looking over his shoulder at Jayjay, his eyes calm and filled with self-knowledge. He had eyes like Bosch.

In that moment Jayjay accepted that he was indeed a glutton. His craving for excess had warped his life. He was finally ready to change. Giving things up had never worked for him, but maybe he could change by adding something in. Instead of quitting, he’d surrender. He opened his heart, feeling a sweet, even glow. God would help him, whatever God was. Everything. Nothing. The harp. The pitchfork. The Cosmos. Saint Anthony’s eyes. It didn’t matter. All that mattered was wanting to change.

“Dear God please help me,” said Jayjay silently to himself, testing out how it felt to pray. It wasn’t about God, really. It was about admitting that business as usual had stopped working. Business as usual was costing him his sanity—and his wife.

While Jayjay mulled this over, Bosch continued painting. The man was a sage, a genius, a prick. Jayjay sure as hell didn’t want to give him the satisfaction of knowing his advice had hit home. So he talked about other things.

“Can I see the harp? Now that the others are gone?”

“No.”

“Um, my wife said you were supposed to decorate the harp to look like your Garden of Earthly Delights. Is that what you did?”

“You’ve heard of this triptych?” said Bosch with some surprise. “How remarkable to have such a worldly apprentice. Have you been in the Brussels palace where it hangs?”

“I’ve—I’ve only seen a copy,” said Jayjay. “In California it’s known as your great masterpiece.”

“A youthful success,” said Bosch. “An early blessing. I weary of hearing about it. I painted the Garden fifteen years ago when I was thirty, during the first year of my marriage. I thought I’d entered a paradise of love, but it proved chillier than ever I thought.”

“You and your wife—do you have children?”

“God did not wish it so,” said Bosch. “Aleid had painful miscarriages and still-births. That part of our life is over. An unfinished path.” He shrugged and sighed. “Better to speak of art. Perhaps this new triptych is the equal of my Garden of Earthly Delights. Or perhaps not. The important thing is that I’m painting it.”

“Who’s it for?”

“It’s a commission from the Brotherhood of St. Anthony here in town; I depict the torments of their patron saint. In the left panel, the devil lifts him high into the sky, in the right panel he’s besieged by lustful women, and in the middle he’s surrounded by monsters conducting a Black Mass. I’m throwing in everything I can think of: some hundred and sixty humans, animals, and demons so far—and that’s not counting the hundred or more soldiers in the little armies. Prickly dots.”

“The Antonite brothers nurse the victims of St. Anthony’s fire,” said Jayjay. “Do you know that condition is caused by a fungus in brown bread? I had an experience of it last night. I spent part of the night hallucinating in the Antonites' courtyard.”

“And drinking wine,” said Bosch, with a telling sniff. “Gluttony. The Holy Fire is caused, like any physical affliction, by sin. God abandons the sinner and the devil attacks like the wolf bringing down a wayfarer. Brown bread is the Lord’s wholesome gift to the lower classes. The bread’s essence is pure in and of itself.”

“My point is that I want to know if you’ve been inspired by hallucinations from brown bread.”

“Were your crippled drinking companions painting triptychs?”

This was leading nowhere. Studying the picture in progress, Jayjay admired Bosch’s facility at turning realistically rendered objects into bizarre beasts. Here was a jug that was a horse, a tree that was a man, a ship that was a headless duck. “Everything’s alive,” he said, returning to their common ground.

“Yes,” said Jeroen busy with his brush again. “Few understand this. I’m glad we share the knowing.”

“Very soon a change will come to ‘s-Hertogenbosch,” said Jayjay. “Everyone will be able to speak clearly with objects, just as they do in my California. That’s what I’m—” he broke off. He’d been about to reveal his plan to play the harp. But it would be better to approach her alone, lest Bosch make some objection.

After awhile, Bosch ran out of paint. He took Jayjay downstairs and demonstrated how to make paint by mixing ground pigments with oil and beeswax. And then, unexpectedly, he gave Jayjay a painting lesson.

“Here,” said Bosch setting a rectangle of wood in front of Jayjay along with a brush, a palette and four pots of paint: white, blue, yellow, red. “I want you to learn to paint foliage. I have a particular model in mind. Wait.”

The master walked back through the house, greeted Aleid, proceeded into the back garden, and returned carrying an enormous uprooted thistle plant, complete with purple flowers and downy seeds. He squashed the thistle down on itself, making a mound.

“You’ll paint this, and you’ll learn to do it right,” instructed the artist. “I’ll watch for awhile.”

Jayjay experimented with mixing the colors to make some good shades of green, sketched in the vine, and added the leaves. The result was inchoate and soggy.

“At least you work fast,” said Bosch. “Now let the light come down like snow.”

Jayjay tried brightening the tops of his painted leaves and vines, but the wet oil paints slid and wobbled, with muddled results.

“Think ahead so you don’t need layers,” said Bosch. “Mind the light.” He produced a rag and rubbed all the paint off the wood. “Try again.”

This time, Jayjay worked with a broader spectrum of shades. He liked mixing the oil paints, liked the alchemical way the colors changed. His new leaves looked quite tolerable.

“Now for fantasy,” said Bosch. “Paint more than you see. Let the shapes dance.” He swept his sinewy hands through the air, limning sweet curves.

Jayjay tried extending the tendrils of the vine he’d drawn, and this went well enough, but when Bosch asked him to add seedpods and little birds, the thing turned into another brown pudding.

“I’ll leave you to paint a third version alone,” said Bosch, rubbing off the panel once more. He tossed the thistle into a corner. “Just dream this one. I’ll be upstairs, giving Saint Anthony another tormentor. A head walking on two feet: a man who’s lost his core.”

Jayjay’s third mound of vegetation turned out well. He liked painting. Somehow the work connected into him all the way down. When he pretended to be a scientist, he was always striving, always playing catch-up ball. But this was free play.

A sound of cooking came from the kitchen, and good smells. Dill, onions, fennel. It was dusk. Outdoors the noise of the market continued as loud as before, but with a different tone: more yelps, more music, and fewer sounds of animals. Party time. But not for Jayjay. Not after today. He’d surrendered. He was a recovering glutton.

He kept thinking about Thuy. Was she really pregnant? Hopefully she’d be back soon. The Muddy Eel sounded sleazy.

Just as he was about to take his panel upstairs to show the master, a heavy knock sounded on the door. Kathelijn ambled out of the kitchen and opened it.

“Good evening, Mijnheer Vladeracken,” said she, admitting a sumptuously dressed fellow with a flushed, piggy face.

“I’ve been chatting with Wim the vintner in the market,” rumbled Vladeracken. “Here.” He handed Kathelijn a half-empty bottle of wine with no cork in it, then glared down Jayjay. “What’s this smeary devil doing in here? I saw him preening on your front steps this afternoon.”

“My new assistant,” said Bosch, coming down the stairs. “Cunning little fellow, eh? His name is Jayjay. Jayjay, this is my neighbor Jan Vladeracken. Let’s settle down in the kitchen.”

Bosch, Vladeracken, Jayjay and Aleid sat at the kitchen table while Kathelijn tended a kettle on the fire. She was stewing the fish and eel with milk and turnips.

Vladeracken filled a pottery mug with his wine. Bosch and Aleid took some wine as well, but Jayjay declined, still drawing strength from this afternoon’s illumination, his mind reverberating with the knowledge that no longer needed to be a glutton.

“I’m concerned about our painting of John the Baptist,” said Vladeracken in a tendentious voice.

Bosch rolled his eyes and didn’t answer. Aleid took up the slack.

“How do you mean?” she asked.

“As you remember, I commissioned this work from your husband when I was the dean of the Swan Brotherhood of Our Dear Lady.”

“Really, Jan,” said Aleid wearily. “Certainly we’re proud that Jeroen’s a member of the Swan Brotherhood, but this endless bickering is so—”

“This is more than bickering,” said Vladeracken angrily. “It’s an attack on my mortal soul.”

Aleid said nothing, only shook her head. And for his part, Bosch mutely peered at Vladeracken and made making painting motions with his hand, as if he were depicting his neighbor upon an invisible panel in the air.

“Tell me the story,” said Jayjay.

“No one cares but the ill-begotten dwarf,” said Vladeracken. “Here’s the tale, little man. I issued Jeroen the commission to paint John the Baptist for our brotherhood’s altarpiece in the cathedral. Therefore it was my right to have myself depicted in the panel as the donor. Settled and done. My image lives in the Lord’s house. God notices these kinds of things. It will be an incalculable benefit for me when I’m judged. Do you follow me, runt?

“Yes, yes,” said Jayjay, not liking the insults.

“You’re impatient with Jan too, eh? Well, listen to the twist. Victor van der Moelen, that walking piece of shit who’s the new treasurer of the Swan Brotherhood—he says that I had no right to appear on the panel as the donor. For the painting was bought with the society’s funds, not mine. I’m perfectly willing to reimburse the Brotherhood, but van der Moelen says that won’t do. And now—”

Bosch twinkled and made rapid motions with his imaginary brush, as if erasing the imaginary portrait he’d just drawn.

“If you paint over me, I’ll have your hide, Jeroen,” bellowed Vladeracken. “I’ll send my pigs into your garden. I’ll bring bagpipers to your steps every day. I’ll denounce you to the priests for saying everything’s alive!”

“You have to go rest now, Jan,” said Aleid, getting to her feet. “You don’t want to miss the vigil tonight.” Her chilly gaze skewered the meaty Vladeracken. “Go home to your wife.”

“Forgive me,” said Vladeracken, suddenly remembering himself. “My humors are addled. The hot sun in the marketplace. Surely you understand.”

“Out now,” said Aleid.

The bully shuffled to the front door and left.

“I could paint over his image for you,” suggested Jayjay to Jeroen.

“Exactly,” said Bosch. “That’s what I’ve spent the afternoon training you to do. Bury the pig-man with writhing vines. You’ll do it tonight, Jayjay, so that the painting is renewed for the Virgin’s processional mass tomorrow. I’ll be at the Swan Brotherhood building most of the night—our vigil starts the hour before midnight and runs till dawn. This way, nobody can think the overpainter was me. Perhaps the emendation will be viewed as a miracle. The hand of the Virgin herself.”

“What a wonderful idea,” said Aleid in a pleasant tone, humoring Jeroen. “But where’s your wife, Jayjay? Our fish stew is ready.”

Thuy was nowhere to be seen. Although she hadn’t said for sure she’d come back for supper, Jayjay grew increasingly worried. He wanted to run straight to the Muddy Eel to look for her, but Jeroen detained him with a seemingly endless discussion of the details of tonight’s commando overpainting raid.

Aleid stayed well out of the conversation; Jayjay had the impression she’d heard enough about the John the Baptist panel to last her a lifetime.

After supper, Jayjay helped Jeroen prepare a little box with a brush, a small lantern, and six stoppered vials of paint premixed to shades of yellow, rose and green. Jeroen drew a floor-plan of the St. John’s Cathedral, and then a detailed blueprint of the Brotherhood’s altar, and then two sketches of the targeted panel: one with the small kneeling figure of Vladeracken, the other with a fantastic, snaky, spiky plant in the donor’s place. Jeroen wielded a wonderfully nimble pen, quite mesmerizing to watch.

Finally Jeroen was ready to leave for his all-night vigil. Unless Vladeracken were passed-out drunk, he’d be in attendance as well.

“I’m sure your wife will be here by the time you’re back,” Jeroen told Jayjay reassuringly. But then a sly, waggish look crossed his face. “Unless she’s drunk or working as a prostitute.”

“Oh, thanks so much,” said Jayjay flaring up. “Which deadly sin is it when you’re a selfish, inconsiderate jerk?”

“Pride,” said Bosch, far from abashed. If anything, he was enjoying Jayjay’s reaction. “May the Lord Jude forgive us our pride, anger and gluttony that we may ever hew to the one true path. Kathelijn, run across the square and get Goossen’s son Thonis. He’ll be your guide, Jayjay. I’m leaving now. God bless you. Truly, I’m sure your wife is doing fine.” Was that a mocking flicker of his lizard tongue? He was gone.

Thonis proved to be a lively youth with a ready laugh, which rang out loudly as Jayjay explained his mission.

“My uncle’s been talking about this for months,” said Thonis. “He’s a wonderful painter, but he’s crazy. Nobody really cares about that panel except Jan Vladeracken and Uncle Jeroen. And maybe Victor van der Moelen. Van der Moelen is the duke’s rent collector; he’s the kind of man who looks at a newborn babe and sees a page of numbers.”

“Vladeracken said van der Moelen is a walking piece of shit.”

“Yeah? What does that make Jan? A talking pig? Never mind. The reason you’re perfect for this job is because you’re so small. They lock the church at midnight, you know. We think it’s best if you go in there now, hide till after closing time, overpaint the panel, then climb out through one of the slits in the tower. I’ll be waiting for you.”

“How high above the ground is the slit?”

“Too high to jump,” said Thonis. “Can you fly?”

“What are you talking about?”

“I heard you’re miraculously strong. From the Garden of Eden.

“What if we bring a rope with a hook on it?”

“I know where to borrow one of those,” said Thonis. “I have a friend who’s a chimneysweep. Come along; we’ll get the rope on our way.”

“Can we stop by the Muddy Eel?”

“The Muddy Eel, no, that’s in the wrong direction. And we’d have the cross the marketplace to get there. The plan is that we sneak along the canal to the cathedral. Maybe you can visit the Eel after we’re done. They’ll be carousing till dawn.” Thonis pranced slowly through a few steps of a jig. “Oh, before we leave, let me take a look at Uncle Jeroen’s studio. I always like to see what he’s been up to. What a mind he has, what a brush. If he would only shut up about hell and sin, I’d still be his apprentice.”

Upstairs, Thonis studied the square panel, and Jayjay looked out the window at the marketplace, hoping to spot Thuy. People were drinking and dancing while preparing their banners and floats for the procession. Bonfires and lanterns lit the scene. It was wonderfully arcane and medieval. A shame not be sharing this with his wife. More than anything, he wanted to become the man she thought she’d married.

Behind him, Thonis was chuckling over one of the little scenes Jeroen had painted onto the temple pillar beside Saint Anthony. “See this?” he said. “A monkey god, with a heathen kneeling and offering him a swan! That monkey looks exactly Victor van der Moelen. And the heathen is my Uncle Jeroen. He had to pay for a swan dinner for the Brotherhood last year, it made him mad, he said it wasn’t his turn yet.” Thonis’s laughter redoubled. “Oh my soul, look at the hog-headed man in his silk robe. Alderman Vladeracken.” Now Thonis gave Jayjay a sly grin. “And that gryllos-man with his legs coming right out of his head? That’s you, Jayjay, with the paint still wet! Nobody’s safe from Uncle Jeroen. He’s been working on this triptych for a year. The Antonites are paying him, and he doesn’t want to stop. It doesn’t hurt that Aunt Aleid is rich.”

“Are you a painter, too, Thonis?”

“In a small way. I paint murals on people’s dining-room walls. Flowers, God in the clouds, the birth and the triangulation of Jude Christ—the usual lot. You’re a painter too?”

“Today’s my first day.”

Thonis puffed out his lips and blew a stream of air. “Good luck making your plant look like one of Jeroen’s!”

But somehow Jayjay felt confident. And then, just before they left Jeroen’s studio, a faint, sweet song sounded through the ceiling. Thonis didn’t seem to notice it. The harp was calling to Jayjay, only to him.

Post a comment on this story.

About the Author

Born in Kentucky in 1946, Rudy Rucker studied mathematics, earning a Ph. D. from Rutgers in the theory of infinite sets. He worked first as mathematics professor, and then as a computer science professor, coming to rest in Silicon Valley.

Rucker has published twenty-nine books, including non-fiction popular-science books on infinity, the fourth dimension, and the nature of computation. A founder of the cyberpunk school of science-fiction, and two-time winner of the Philip K. Dick Award, Rucker also writes SF in a realistic style known as transrealism.

Rucker is currently working on cyberpunk trilogy in which nanotechnology augments human mental powers but threatens to destroy Earth. The first volume, Postsingular, will appear from Tor in October, and, starting in November, Postsingular will be available for free download at the Postsingular web page.

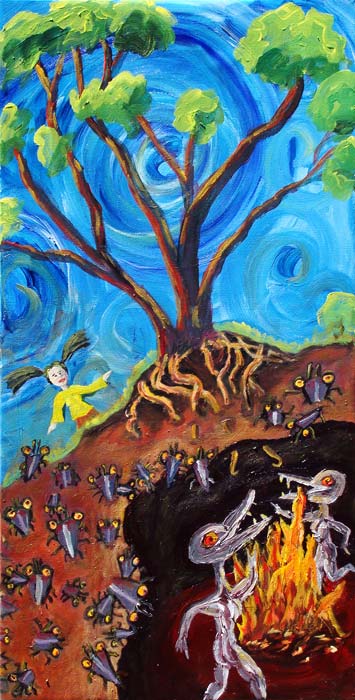

"Hieronymus Bosch's Apprentice" is drawn from a chapter of Rucker's novel-in-progress Hylozoic, the second volume of the series. Rucker's paintings for this story are the central and left panels of his Hylozoic triptych; the right panel depicts a giant beanstalk.

A exhibition of Rucker’s paintings will be staged at Live Worms Gallery in San Francisco, Friday to Sunday, November 9 -11, 2007, with a reception and readings. Click here for details.