Kistenpass

by Kim Stanley Robinson

During our last summer in Zürich I tried to get up into the Alps as often as I could. I spent many evenings hovering over a plastic three-D map of Switzerland set flat on our dining room table, getting a helicopter view of the miniaturized mountains. Everything looks possible when the scale is that small. I was searching for likely day trips in the pattern of my Lötschepass crossing, which meant using the massively overbuilt Swiss transport system of trains, buses and cable cars to get to a high trailhead, hike over a pass to some other high trailhead, and return on public transport that same day.

Evening spent like that, deep in my early version of Google Earth, would send me to bed dreaming of potential hikes, so that I would sleep poorly, and wake at five to call the national weather service for the day’s forecast. Very often the recorded female voice would report rain in every region, but on some lucky mornings she would announce in a cheery tone that it was going to be “schön” somewhere I wanted to go, and I would throw my windbreaker and a topo map and water bottle into my daypack, and say good-bye to Lisa as she prepared to leave for her lab. I’d hurry down to our tram stop still eating a pastry, and tram down to the Zürich hauptbahnhof to catch the first train leaving in the direction I wanted. I no longer bothered to check train schedules, having learned to trust the Swiss to link all elements of their transport in a dense network of daily movement. On this day as always I barely had time to buy a ticket and a sandwich and chocolate bar before I needed to get on the express for Chur. At the stroke of six A.M., before I even had time to find an empty seat, we were off.

By seven-fifteen we were in Chur. Quickly I found my next train, which was going to take me up the valley called the Vorderrhein, the watershed of the headwaters of the Rhine River. This train proved to be made up of little old cars, set on a narrower track than normal. I didn’t recognize this might represent a problem for my plans, and read with interest what I could of a poster describing the history of the Rhenischer Bahn, a company that had laid its tracks in the 1860s, and only later gotten connected with the larger Swiss system, keeping however its narrow gauge. I boarded one of the little passenger cars and was pleased to see it was a well-preserved antique, with leather seats and hand-painted trim in typical Swiss chalet style.

Rolling westward out of Chur, I quickly learned that the Vorderrhein was an immense glacial valley, with the classic U shape, and a particularly deep post-glacier river gorge scoring the bottom of the U. This was the Rhine itself, snaking from sidewall to sidewall so that the little train had to cross bridges and viaducts, go through tunnels, and struggle up sharp curves. It seldom got up to fifty kilometers an hour, and was often much slower. And it stopped at every one of the tiny stations along the way. So even though my destination, the village of Danis, was just sixty kilometers east of Chur, it was still going to take about twice the time it had to traverse the hundred and twenty kilometers from Zürich to Chur.

Well, nothing to do but sit back and watch the scenery. It wasn’t even eight o’clock yet, so I had some time to spare.

The other passengers in my car were conversing in what I assumed at first was German—except it sounded Italian. It sounded as if they were arbitrarily mixing German and Italian, and eventually I realized it must be Romansch they were speaking, the fourth official language of Switzerland, which I had read about but never heard. The Swiss had made it their fourth official language during the height of Hitler’s talk of Aryan supremacy, and the history of Switzerland I had read was obviously proud of this small rebuke to his racism. About 50,000 Swiss were said to speak it at home, with 200,000 more in Italy and Austria. Despite these small numbers, I had been shown Romansch science fiction novels published (with the help of state subsidies) in handsome hardback editions of five thousand. But I had never heard the language spoken, and now it was a pleasure to listen to it as I looked out the window and tried not to get impatient at the many stops. Just throw German and Italian in a blender, I decided, and you would have the sound of it exactly.

We passed under Flims, the big town of the valley, which was perched over us on a broad bench on the north slope. I had read that the entire bench was the remains of a single immense landslide. This landslide had been dated to about twenty thousand years before, after the most recent Ice Age glacier had retreated upvalley. It was the biggest identifiable landslide in all Switzerland, and clearly the Swiss were pleased to have been able to set an entire town on it.

An hour after passing under Flims we stopped in yet another tiny station, and this time everyone got off the train. I didn’t understand until a conductor came through and conveyed to me, in German I could barely understand, that I too had to get off. Some kind of problem, it was clear—Erdrutch, I heard him say, which sounded like earth rush. Another landslide!

The conductor nodded at my look of comprehension. He then seemed to be telling me that a postal bus would carry all passengers past the blockage to the village of Trun, where another train awaited us.

But I didn’t want to go as far as Trun, I told him awkwardly. I wanted to go to Danis, and then up the valley wall to Breil, where a cable car would take me up to the alps below Kistenpass.

The conductor nodded and led me off the train to a schedule posted on the station wall. Apparently I was in Tavanasa, right next to Danis, and a bus would be leaving here for Breil at noon.

While I was still deciphering all this the conductor got on one of the postal buses carrying the train’s passengers, and they all drove off. The train itself backed down the valley and disappeared around a bend. I stood alone in the empty station of Tavanasa, five hundred meters below Breil, and two thousand meters below Kistenpass itself. It was now ten A.M., and I had thought I would be in Breil by nine. And the noon bus wouldn’t make it there till one.

I decided to run up the road to Breil. I was only carrying my daypack, and running would be my only chance to get anything like back on schedule. So I began to jog.

Up the road I ran. Quickly I broke a sweat.

Very soon I saw that in this part of the great valley the northern wall of the Vorderrhein was steep but smooth, and on such slopes the Swiss like to grade their roads very gently, in long traverses and tight hairpin turns. At every switchback I could look down on the one below and see that a run of perhaps half a kilometer had netted me a vertical gain of about twenty-five meters. A quick calculation suggested that although as the crow flies it was only two kilometers from Tavanasa to Breil, as the Stan ran it might be more like fifteen kilometers, maybe twenty.

I began to hitchhike.

I continued to walk uphill, and jogged from time to time, but whenever I saw a car coming up the road I turned around and stuck out the old thumb. I had hitched a lot in my twenties, but never in Switzerland, and trying it felt a little crazy. Most of the cars that passed me were filled with guys in their Swiss Army uniforms, and they stared at me in a way that made it clear I was right to feel that way. Their looks made me wonder if there was a regulation forbidding Swiss men on Army duty from picking up hitchhikers. If there were, I was out of luck; compliance with regulation was a fundamental part of the Swiss character, as I had learned on many occasions. One time, for instance, I was playing American football with my Swiss baseball teammates and three or four Americans, a pick-up game at the big Zürich sportsplatz where we played baseball, and the Americans were gathering the huddles and calling plays that degenerated into chaos the moment the ball was snapped, lots of mayhem that was never allowed in soccer, so that everyone having a blast, except suddenly all the Swiss quit the game and started walking off the field. When asked what was up, they explained that it was six P.M. and the sportsplatz closed at six, every day, even in the summer when the sun was still halfway up the sky. We Americans were amazed at this, and suggested we continue to play anyway, as it was a stupid rule and there was no one there to close the park, or even notice it was being used. But this was inconceivable to the Swiss guys, they just shook their heads and kept on walking, until one particularly rowdy American named Richard started shouting,”What? What? What is this? What kind of Nazi shit is this?” I thought the Swiss guys might get angry at that, but they only gave him the same cold look that I was getting now from the guys in the cars zooming by, a look immensely distant, as if from a world no non-Swiss could ever understand.

As I trudged up the road I recalled a Swiss friend trying to explain that world to us, one night after dinner. Every year on the night before Christmas, she told us, Sami Claus came to the door of every home in Switzerland, accompanied by his sidekick the Böögen, a tall creature draped in a big black bag and carrying another black bag in his hands. Sami Claus would then consult with the parents about their children’s behavior in the previous year, and the parents would produce an account book they had supposedly been keeping to record their kids’ behavior. If the children were reported as being good, then they would get a gift from Sami Claus; if they had been bad, the Böögen would snatch them into his bag and take them off never to be seen again. The children were brought to the door to witness all this, and the youngest ones believed it was real. “And that,” our Swiss friend concluded, “is why I hate Switzerland forever.”

So I had given up all hope of catching a ride, and wasn’t even turning around to face the passing cars, when a Mercedes slowed ahead of me and came to a stop. I ran up to it; the driver was a woman, and she had two kids in the back seat. I thanked her as I got in, wishing I weren’t so sweaty, but she didn’t seem to notice. Off we went.

My Swiss benefactor was blond and good-looking, and seemed capable and sympathetic. In my hitchhiking days whenever women picked me up I pretty much fell in love with them immediately. Now I was remembering how that felt, and kind of feeling it again. She was saving my day. She asked me politely where I was going, and in my broken German I told her about my disrupted morning, and my plan for the afternoon.

“Kistenpass!” she repeated, surprised. (“Keesh-tee-pahsss!”) But, she said, glancing at me as she drove, the cable car above Breil was a ski lift only. In the summer it was closed. Very few people ever hiked over Kistenpass.

That is bad news, I replied.

I began to think I had under-researched the trip. Maybe my method of going out with only a topo and the information I could glean from my plastic three-D map wasn’t such a cool thing after all.

The kindly Swiss woman turned off on a side road by a small building called the Hotel Alcetta, still well below Breil. She told me there was a PTT phone booth in the hotel’s entry, and suggested I use it to call a taxi that ran out of Breil, and ask it to come down and give me a ride. I thanked her again, and went into the hotel and made the call, and told the man who answered where I was and where I wanted to go. Then I went back outside and started walking up the road again, figuring I would see the taxi coming down for me.

But no taxi ever passed. In desperation I started hitching again. Too bad that woman had not been going to Breil, or hadn’t been even more of an angel than she had, and given me a ride all the way.

Then another farm wife stopped for me. I got in her Jeep feeling really fond of the women of the Vorderrhein. I repeated my story, and she too exclaimed “Keee-stee-pahsss!”

By the time I was done describing my day we were in Breil’s town square, and she was dropping me off at the door of the tourist office. It looked like a village more devoted to farming than tourism, and the office appeared closed. But the door opened when I tried it, and a surprised young woman looked up from the book she was reading . She too heard out my story. Her English was almost as bad as my German, but between us we confirmed that I had wanted to take the cable car up toward Kistenpass, but that I had learned already it was closed for the summer.

She suggested I call the village’s taxi service and ask him to take me up the farm roads above the village—these went all the way up to a dairy that was actually a little higher than the cable car’s upper station. The dairy was in fact the real trailhead for the Kistsenpass trail. The taxi fare would be about thiry francs, she guessed, meaning about twenty dollars, and the vertical gain, I saw on my map, would be about eight hundred meters. Such a deal! Cheap at the price, in fact, as it would put me back on something like my schedule.

I conveyed this to the young woman, and she called the taxi for me. A few minutes later it rumbled into the square: a big black pick-up truck, with huge snow tires and radio gear sticking out all over it—a truck that had in fact passed me going downhill as I was walking up from the restaurant. I had been expecting something more cablike, although now that was obviously a silly expectation.

The driver got out and shook my hand. He was a big man wearing blue jeans and a plaid shirt, with thick black hair, a round face, and a cheery manner. He spoke no English at all. I explained in German where I wanted to go, and he nodded and made a gesture: in you go! And off we went.

The steep one-lane road we ascended ran in switchbacks past several of the characteristic farmhouses one sees in the high alps. The taxi driver, whose name was Mario, talked about these houses as we drove by them. His German was amazingly clear to me, probably because he was from Ticino and his first language was Italian. The farmhouses, all enormous, were usually attached to even larger barns, and together they housed both the herders and their herds. Dairy farming at such altitudes was hard, Mario said, but they had been doing it for many generations, and had their system perfected. The green alps themselves were creations of the herders—huge lawns, in effect, cleared of their original load of forest and rock. The centuries of labor necessary to achieve that kind of a transformation was mind-boggling to contemplate. We agreed that it was part of what made the Alps feel strange—both safe and dangerous, domestic and wild—a pretty park that in half an hour could turn nasty and kill you. I mentioned Muir’s famous description of California’s Sierra Nevada, as gentle wilderness; we agreed that the Swiss Alps could well be called savage civilization.

Passing one of the big barns, I mentioned that I had once hiked by one just as it was being opened up for the spring, and how struck I had been by the sight of the astonished new calves staggering in the sunlight . Mario laughed and said that was one of his favorite sights of spring. They see the sky! he said. For the first time they see the sky, and it blows their mind!

At these altitudes, Mario went on, dairy farming was unprofitable. The government subsidized it, paying more the higher the farm. But it wasn’t enough to keep the young people at home. The houses had been built to hold extended families of three or four generations; now they were mostly empty, kept going by husband-and-wife teams and maybe a couple of kids. The homes had become like millionaire’s mansions, much too large for their occupants. People thought that would be great, but it wasn’t so. It would be sad.

Too much money makes you sad, I ventured.

I wouldn’t know, he said with a laugh. I’m very happy myself! I live in a suitcase! I live in this taxi!

He had lived in many places since leaving Ticino, including Zürich. His German was fluent, but he didn’t appear to care about or even to notice my grammatical blunders, which were many. As he said when we discussed it, if you get your meaning across, the rest doesn’t matter. This thought made me even more comfortable, and I damned the torpedoes and sped full ahead. And I suppose it is also true that I had finally crossed some threshold in my miserable German. Lisa and I had been going to night classes twice a week for nearly two years, and they were finally beginning to have an effect: I seemed could hold up my end of the conversation. As we continued up the narrow gravel track we talked about Zürich, about what I was doing in Switzerland, about our wives’ work, about where he had lived, about Ticino and the Vorderrhein, about the German Swiss as opposed to the Italian and French Swiss. I confessed that I had been the one to call him from the restaurant below Breil, but had failed to flag him down because I had been looking for a cab like one from Manhattan or London. He laughed at that, said it didn’t matter, as we had finally met in the end.

That was the best conversation in German I ever had, and when Mario dropped me off at the dairy barn at the upper end of the road, shaking my hand and taking off with a wave, I was really happy. All those dull classroom hours had finally been put to use!

Not only that, but it was only noon! Between the kindness of the Swiss farm women, and the professional help of the tourist gal and Mario, I was not all that far behind my original schedule. Although looking at my map and the slope above me, it did seem that I was going to have to hurry.

#

I took off up the trail, and immediately lost it. That’s hard to do in Switzerland, where most trails are obnoxiously over-signed and as obvious as freeways, especially across the alps, where they are brown trenches in the grass. But this alp was contoured by many narrow dirt runnels, either cow trails or the erosion patterns left by solifluction, and I had apparently taken off on one of these false trails, until it petered out and disappeared.

Probably I had headed out too low. But it was an easy enough slope, so I traversed up the grass, assuming I would soon intercept the real trail.

It didn’t. My traverse began to steepen, and I had to work a little. And apparently it was fly season here. There was only one kind of wildflower to be seen, a yellow thing like a daffodil; and this flower apparently attracted flies. There were hundreds of them, even thousands, even tens of thousands, all buzzing in the air. I had never seen flies in the Swiss Alps before, and these were big ones that liked to land on you and then bite, or maybe it was only an exploratory pinch, but it hurt. I hiked along slapping at my legs and cursing, and cutting a higher and higher line in hopes of intercepting the trail and then running to escape them. Eventually I turned and hiked straight up the slope, intent on finding the trail as soon as possible. The slope steepened again and I ended up climbing a grassy wall, using my hands to pull myself up from clump to tuft to clump—and here I was only ten minutes into my hike!

Finally I intercepted the trail. It made a decent contour across the slope, as expected, and I did as planned and ran along it to escape the fly zone. But there proved to be a number of little pastures to pass through, and the flies pursued me for a long time, because the little pastures all sported summer barns that were as dirty as any buildings I had ever seen in Switzerland. The Disney spotlessness of the tourist zone and the German Swiss cantons generally had here given way to a grubby working landscape, hot and glary and dusty and flyblown. It looked like a ranch in Nevada.

I turned to look south and remind myself where I was. During the ice ages the Alps were covered by much thicker and longer-lasting glaciers than California’s Sierra Nevada, and as a result the Alps’ valleys are much steeper and deeper. The high lake-filled basins that characterize the Sierras are extremely rare in the Alps, because they were ground away, leaving only the famous horns, knife-edge ridges, steep green walls, and immense gulfs of air. Looking over the five thousand-foot drop of the Vorderrhein toward Italy, I thought I could see the curvature of the Earth. Well okay maybe it wasn’t Nevada.

Turning back to my hike, I ascended a rocky hill and felt as if I were finally getting down to business. It was about one in the afternoon. The trail now began switchbacking, up toward a notch in the ridge above. Granite broke out of the grass, in forms big and small: sand, scree, talus, boulders, bedrock. Soon there was more rock than grass, and the little meadows that remained were filled with the full array of Swiss wildflowers, including moss campion, which is like a pincushion of dark moss stuck by a circle of tiny pink flowers. Moss campion and blue cornflowers were my favorites, and there were lots of both scattered over the dark orange granite, fine-grained and handsome. Yes, I was finally getting up into the god zone.

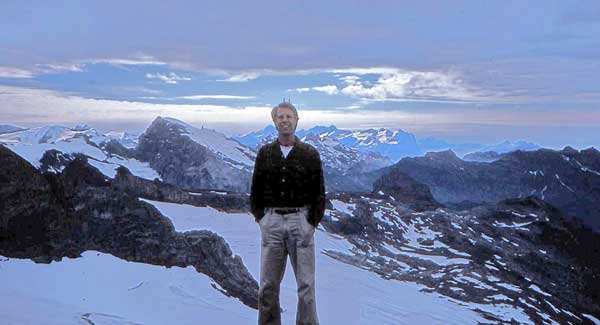

Soon I was through the notch on the ridge, and crossing a small tilted granite bowl above it, where the rock was half covered with snow. Trail signs pointed to the upper rim of this bowl, called the Cavorgia da Breil. The low point of the rim was Kistenpass itself. The pass!

I tromped happily up old snow to the ridge, and was soon in the pass. Up there I discovered, as one often does, that the landscape on the other side of the pass was very different from what I had seen so far. I was looking north along the western side of a long steep ridge, called the Muttenbergen, which ran to a peak called the Muttenstock, then dipped and continued up again to a peak called the Ruchi. The west side of the Muttenbergen dropped very steeply into a lake called the Limmerensee—1200 vertical meters in less than a kilometer horizontally. The steepness was not continuous, happily, but rather a matter of two cliffs, high and low, separated by a band about the steepness of a church roof, still covered with snow. This snowy stretch was called the Kistenband, and my way forward ran over it. The pitch looked a bit uncomfortable, but given the cliffs above and below, there was no other way forward. Unfortunately the trail lay under the snow.

Well, a line of bootprints in the snow showed me where the trail no doubt ran. I took off and followed them. The Kistenband: it was a good name. I was no longer surprised that a feature like this had a name;.I had learned that the association of the Swiss with their Alps had gone on so long that were names for practically everything you could name, right down to individual boulders. Ötzi the Alpine Man could have named this band five thousand years ago.

The line of bootprints in the snow ran a little closer to the lower edge of the Kistenband than I would have liked, but the untrodden snow above it was much slippier, so there was no good alternative to following the tracks. The bootprints were only semi-frozen at this point in the day, both slick underfoot and with a tendency to collapse down and to the left. Where the Kistenband ended the cliff fell away so steeply that I could see not see anything of the lake below, but only knew it was there because of my map, which showed it was a long narrow reservoir, a thousand meters lower. Knowledge of this drop was making the Kistenband begin to seem a little too steep. The bootprints got softer by the minute, and with every step I slid a little down and to the left. Walking poles would have been great, an ice axe even better, but I had not expected snow. It was August 12 th, and I was only at 2700 meters on a west-facing slope, and in the Sierras. . . well, I had already learned the Alps were not the Sierras. Now I was learning it again. All I could do was go slow, and pay really close attention to my footing, staring at the snow under me until my pupils had contracted to pinpricks. Whenever I paused to look up the world had the dim look of a photo negative. The sky looked dark, even the snow itself looked dark.

This went on for what seemed like a long time, but in fact the Kistenband is only about a kilometer long, and my traverse probably took no more than half an hour. But it’s a big world at times like that. Every time I slipped chunks of ice clattered down to the left and disappeared over the cliff, and while it seemed likely I would be able to drag myself to a halt if I fell and slipped myself, it wasn’t the kind of theory you want to give a practical test.

So when I came to the widening at the north end of the Kistenband, where the slope lessens, I stopped and took a breather. There was a spur just below me to my left, jutting out over the Limmerensee, and to my surprise a little roof top poked out over the last rock. I walked over and found a tiny shed tucked under the spur. Possibly an emergency hut; but its door was locked, and there were no signs on it. Maybe it was a storage shed for cowherds, or trail crews. In any case there it was. The top of the spur above it was clear of snow, and had a magnificent view; and I was past the crux of the hike, and suddenly hungry. I sat down to eat my lunch, feet kicking over the edge of the rock.

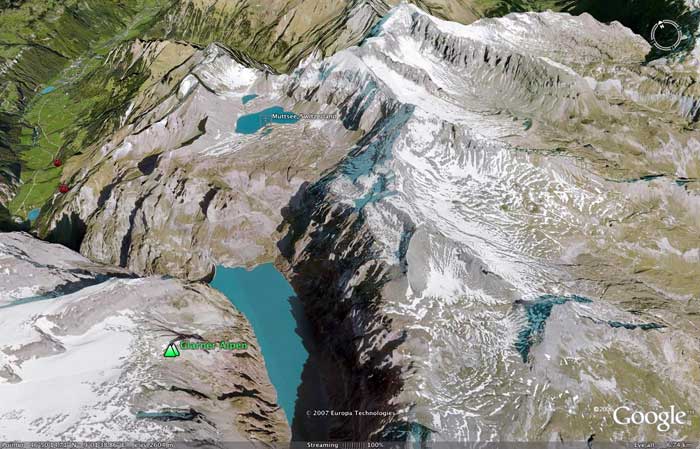

Checking out the next section of my hike, behind me and to my right, I could see that the ridge of the Muttenbergen curled like the top of a question mark, arcing from the Muttenstock to a peak called the Ruchi to another called the Rüchi. Tucked in the curve of the question mark was a snowy basin called the Mutten, filled for the most part by an icy lake called the Muttsee. I could see the trail as a line of bootprints running across the snow covering the rib that held the Muttsee in place, and there on the rib stood a little square dot, black in the piebald mix of snow and rock. My map identified this building as the Muttseehutte, SAC (Swiss Alpine Club). When I got there it would be caffe fertig time for sure.

Under my feet the space over the Limmerensee looked like an enormous roofless room, long and narrow, with the lake as its blue carpet. The wall on the other side of the lake was a horizontally banded cliff, rising sheer from the water to my own height; above that it broke up and lay back in a wild jumble of snow and boulders, ending in a jagged skyline that ran from peak to peak—from the Vorder Selbsanft to the Selbsanft to the Hinter Selbsanft to the Vord Schiben to the Hinter Schiben. All these names made sense in relation to my vantage point, as if they had been named from there.

The Muttsee and the Limmerensee were both blue, but the blues were very different. The Muttsee was the brilliant turquoise of water lying over submerged ice, under a clear sky. The Limmerensee, on the other hand, was a reservoir, and its catchment basin included two hanging glaciers that added glacial milk to the clearer waters coming in from elsewhere. The resulting mix was the opaque virulent blue of radiator antifreeze.

The reservoir flooded a valley which must have been quite something before it was drowned. The mapmakers had retained the contour lines of the submerged area, turning them blue rather than the usual brown, and these showed what had probably been meadow or forest, or a mix of the two, with the Limmerenbach running down the middle. It might have looked like Yosemite; but this had not stopped the Swiss from damming it. In their drive for electricity they had dammed and drowned many of the deepest gorges in the Swiss Alps. I suppose you can’t afford to regard sixty-five percent of your country as an untouchable wilderness, but I was still a little shocked whenever I saw how relentlessly they have altered their landscape. We’ve done a lot of it in the Sierra too, but nothing compared to them. No doubt a hidden valley like this one never had a chance.

And yet it was still a great space; and the Muttsee at least was still beautiful. I pulled my bahnhof sandwich from my daypack, pleased with my lunchtime prospect.

As I began eating I heard a buzz from below, and spotted a helicopter the size of a mosquito, floating just over the antifreeze. It rose in slow spirals, working hard to gain altitude. No doubt it was climbing to resupply the Muttseehutte: I had been at other SAC huts when helicopters flew in with supplies. It was going to be interesting to watch it from this distance.

The helicopter rose in an expanding spiral that used the entire space of the gorge. It took at least ten minutes for it to ascend, giving me a sudden new sense of just how deep the gorge was. It’s hard to see vertical distance; the eye has a predilection to see all great heights as about a thousand feet, a foreshortening error that does not go away even when you know about it. Now the helicopter’s long struggle was making the real height of the gorge evident.

Eventually it completed its climb and banked in a final spiral that brought it under my part of the cliff. I was going to get a good view of it as it passed me by. I sat on my overlook and observed its two circles of blurred blades, big one horizontal, small one vertical. They are strange machines. The engine noise, which had started as a mosquito buzz, was now a roar. It was really going to pass close to me.

Then it rose to my level and hung right before me, making an incredible racket. It turned toward me, and I found myself looking into its bubble windshield, eye-to-eye with the pilot. He was a black man, wearing mirrored sunglasses and big earphones. I thought he looked American, and waved at him, but his hands were busy and he didn’t wave back. I saw his forearms shift on his controls, and the helicopter tilted forward and began to drift straight in at me.

“Whoah!” I said. What the hell? The helo was still closing, the pilot’s face was still blank. I scrambled to my feet, turned and retreated quickly onto the spur’s flat top. I looked over my shoulder to be sure all was well and was astonished to see the helicopter was topping the spur and turning down toward me, louder than ever.

I bolted up the hill in a panic. The blast of its wind buffeted my back, and in the horrible roar I dared a look over my shoulder, terrified of what I would see—

It was landing on the flat spot behind the spur.

I stopped running. All was suddenly clear: I had been sitting on the edge of his landing pad. It was the only flat spot around. He was bringing supplies to the little locked shed under the spur.

Well of course! I had not fallen into a horror movie after all! I should have been able to figure it out earlier.

I stood there feeling my heart blast the blood through me. All my capillaries throbbed at every hit, and my vision was bouncing.

The pilot killed the engine and climbed out of the cockpit. I walked back down the hill toward him, anxious to apologize for taking so long to figure out what was happening.

He saw me and said something before bending to his cargo door, but there was still lot of noise and I couldn’t hear him. I came a little closer to yell that I didn’t speak much German, and all of a sudden he straightened up and shouted, “ACHTUNG!”

I stopped in my tracks. He pointed up at the blades still thwacking the air overhead. In that instant I saw that as rotor blades slow down they become visible from the inside out. What I had assumed were the ends of the blades were actually just the ends of their visible part. Looking more closely I saw the faint blur of sky that marked their real ends; the blades were about twice as long as I had thought they were. Not only that, but as they slowed they were beginning to droop, and I was descending onto the flat from the slope above. So the actual tips of the blades, now quite visible to me, were at my head level, and about fifteen feet away.

I turned and walked off. The pilot was busy anyway, and I had lost all interest in talking to him. I got out of there.

Several minutes down the trail I noticed that my half-eaten sandwich was still in my hand, squished into a ribbed tube of dough. I nibbled it as I hiked, and realized after a while that I was too deaf to hear myself chew. I looked back once or twice without intending to. I came to some of the deepest suncups I had ever seen, skidded this way and that on snow that had lost all structural integrity. It didn’t matter; I wasn’t there anyway.

When I trudged up the final approach to the Muttseehutte I was really ready to sit down and have a caffee fertig or two, or three. After that I would continue over a nearby rise called the Muttenchopf, and descend to the cable car that would drop me to the road at Tierfed.

The hut keeper was standing on the porch outside his door. He greeted me as I approached: “Grüüüüt-zi!” It was the Swiss greeting at its most Swiss.

He was short and bald, barrel-chested and suntanned, with immense forearms. He asked me where I had come from and I told him, re-entering that zone of competence in German that I had magically occupied during my time with Mario. The hut keeper asked questions about snow conditions on the south side of the pass, and I described what I had seen, and it was all as clear as could be. I did not attempt to tell him about my encounter with the helicopter, which was beyond my German to express, and so the conversation proceeded well. At one point, enjoying my ability to do it, I asked him how long it would take me to hike over the Muttenchopf, and when the last cable car of the day left Galbchopf for Tierfed.

The question startled him: Why? he asked. Did I want to take it?

Exactly, I said. I did want to take it.

He walked across the porch to me and said very firmly, “Du muss schon gegangen sein!”

You must already gegone to be.

I thought it over; yes, that was what it meant; most of the words were utterly simple, and I knew very well that “schon” meant “already,” because that was what I used to yell at my Swiss baseball teammates when they did something good, meaning to yell “schön” like they did, a mistake that had given them no end of amusement before they had finally corrected me. So:

You must already be gone!

“Whoah!” I said. The hut keeper nodded as he saw I understood, just as the train conductor had that morning. He took me by the arm and walked me down to a trail sign just below the hut. In rapid but still magically comprehensible German he told me that the trail that went down to the dam, and then through a tunnel to the cable car station, was a much faster route than the trail over the Muttenchopf—so much faster that it was my only hope of catching the last car, which left at 3:45.

It was now 3:05. I got out my topo map and he nodded approvingly and traced with a thick finger the trail I should take. “Fiertzig minuten,” he said emphatically. Forty minutes. And then he stepped back and cried, “Fliegst du!”

FLY YOU! Yikes! No more than five minutes had passed since my arrival, and here I was waving good-bye to the hut keeper and running down the trail, over the lip of the Mutten and down a steep green bowl to the shore of the virulent Limmerensee.

The trail was snow-free, and dropped down gullies and over grassy humps, and most of the time I could run it. Where the trail banked against rock walls there were cable handrails bolted into the rock, and these helped me maintain a good speed even when things got quite steep.

After about ten minutes of this I paused to catch my breath and eat my Toblerone bar, and look again at my map. As soon as I calculated the altitudes and distances involved I took off again, running down the trail faster than ever. Forty minutes! He was crazy! The drop to the lake was six hundred and fifty vertical meters, and the tunnel looked to be about three kilometers long! No way!

But way. He had said it was possible, and he wouldn’t have said it if he hadn’t been sure. He had done it. Those Swiss Army guys passing me by in their car could do it, each chased by his own personal Böögen perhaps, but they could. If they couldn’t the hut keeper would have told me to forget it, that I should stay the night at his hut,where there would be a radio phone that I could have used tell Lisa what had happened. Then I could have relaxed on the hut’s porch drinking caffee fertig,, or just the fertig (cognac), while watching the evening alpenglow light up the Muttenstock. That was a good idea, now that I thought of it, but instead here I was hauling ass down the trail like a Keystone Kop, cursing the Swiss with every leap. Have a nice day in the Alps, I shouted as I plunged. So relaxing! God damn you guys! God damn your cable cars, and God damn you for closing the fucking things eight hours before dark! When you bother to keep them open at all! It was ridiculous! But I was going to do it anyway, and without any Böögens to chase me either—just a determination to get home that night, and because the hut keeper had said I could do it.

So I descended 650 meters in twenty-five minutes, certainly my all-time record (at least until I cut my shin on the Black Giant, but that’s another story). I panted along the shores of the radioactive Limmerensee until I was stopped by a cliff that dropped straight into the water. The trail ran right under a black iron door in the cliff.

The tunnel. God damn it one more time. I don’t like tunnels. I approached the door and looked at a page taped to it. The printed message, in German of course, had words so long they crossed the whole page. I couldn’t understand any of it. Apparently my streak of German had ended in the great exchange with the hut keeper. Fly you! I had flown.

I turned the handle and pulled the door open. There was a light button just inside the door, and when I pushed it a line of bare bulbs came on overhead, illuminating a tunnel about nine feet high and not much wider. There were metal tracks, like tram tracks, laid on the tunnel’s stone floor.

I stepped back out into the sunlight and tried to read the sign again. No way. Inside, a simpler note by the light button told me that the lights would stay on for twenty minutes after I pushed the button. Back outside I checked my map again. Yes, the tunnel was between two and three kilometers long. Say a mile and a half. I could run that in less than twenty minutes. And I would have to, not only to beat the lights going off, but in order to get to the cable car station at the other end of the tunnel before 3:45—because it was now 3:31!

I banished my distaste for the tunnel and stepped back inside the iron door and let it clang shut behind me. I hit the light button one more time and started jogging down the stone floor between the tram tracks.

Quickly I was far enough down the tunnel that I couldn’t see the door behind me any more. In both directions the light bulbs ran together into faint lines, which eventually disappeared entirely in the gloom. There were leaks in the rock ceiling, and occasionally I ran under little curtains of dripping water; often I stomped through puddles between the tracks. Getting winded, I checked my watch; I had been running three minutes. Probably my initial pace had been a bit fast.

Very low creaks echoed down the tunnel, as if the rock around me was somehow stressed. Maybe by the weight of all that radiator fluid. If the dam were to burst the tunnel would get torn apart. If an earthquake struck it would collapse. I ordered my mind to stop conjuring such unlikely events, but I have a fear of tunnels, and the infinite regress of dim bare lightbulbs in both directions was a strange sight. I kept on pressing the pace, my boots splashing in the puddles, my daypack flopping on my back, my breath beginning to whoosh in and out. My watched showed 3:35; but then I recalled that it was set five or seven minutes fast, to help me keep up with Swiss timeliness—to help me in situations just like this, in fact. So I had a bit of leeway. And hopefully I was around halfway through the tunnel. It seemed to me that I was running at a nine-minute mile pace at the very least, despite my boots. It all should work.

Twice I passed open black side tunnels to my left, the lake side, and I hurried by them and their wafts of cold air, wondering if they ran out to the dam, or under it. Once as a child I had gone with my parents and brother to Parker Dam on the Colorado River, and we had taken a tour through one of the big turbine rooms, and that night I dreamed we had been locked in there by accident and they let in the water and it rushed over us, causing me to wake up filled with a dread so deep I have never forgotten it. There aren’t that many dreams you remember your whole life. Now I seemed to be running in that dream, and the empty black side tunnels scared me no matter what I tried to think. I suppose it is true that I am still eight years old in my mind.

Thus when I heard a faint roar behind me I first put it down to morbid imagination and tried to ignore it. Then it got louder and was obviously real. A very definite roar in the tunnel behind me—and getting louder! I looked down at the tracks in the tunnel floor: tram tracks. A tram was coming!

I redoubled my speed. Swiss tunnels are often sized only a few inches wider and taller than the vehicles that pass through them. I glanced over my shoulder, in what was getting to be the day’s signature movement, and saw two pinpricks of light. Little headlights under the string of lightbulbs, quickly growing bigger, filling the tunnel as the roar got louder. I turned and ran as fast as I could.

Suddenly the tunnel widened and split into three. I ducked left, into the widest part of the open area, away from the tracks, and pulled up tight against the wall. An old gray VW van with a bad muffler sputtered past me.

Its driver had not seen me, and he drove on. I took off after him, guessing as I ran that the sign taped to the door at the other end of the tunnel had announced the van’s schedule to people wanting a ride. No doubt its last trip of the day was timed to take people out to the last cable car.

The van came to a sudden halt and I almost rear-ended it. We were at the end of the tunnel, it seemed. I had made it in time for the last cable car down.

The driver of the van (he had carried no passengers) turned out also to be the operator of the cable car. I got in the cable car with him, not even trying to explain why I had run the tunnel rather than wait for a ride. He did not seem to be interested in any case. Right before our departure (he was checking his watch to leave at the first second of 3:45), we were joined by an elderly couple in the full regalia of Swiss mountain walking: heavy leather boots, long wool socks, wool knee pants, plaid long-sleeved shirts, suspenders, varnished walking sticks, old leather rucksacks. The man wore suspenders and a jaunty green cap with a feather. The woman’s white hair was perfectly coifed.

When they were in, the driver closed the door and latched it, punched at his control panel, and the car jerked out of the station and dropped like a boulder hung on a clothesline. Down we sailed. Tierfed was a thousand meters below, and watching the cliff shoot by I was very glad I had hurried to make the last car. Without it there was no way I would have made it home that night. Now I would.

When, I asked the van driver hesitantly, suddenly self-conscious about my German again, did the bus leave Tierfed for the train station in Rieti?

He stared at me, surprised. Bus? There was no bus.

I stared at him, appalled. I had never heard of such a thing. All the cable cars had bus connections to the nearest station! It was over ten miles from Tierfed to Rieti, there had to be a bus!

The van driver shrugged. No bus. The elderly couple stared at me. I was still sweating from my tunnel run, and in fact I had broken a sweat several times that day, some of them hot, some of them cold. I could taste the salt on my lips, and feel the sunblasting I had gotten; I knew from past experience that my face would be a flamboyant red, and in the window of the car I could see a faint reflection that showed my hair spiking out as if I had been electrocuted.

So when the van driver suddenly asked the elderly couple if they would give me a ride to the Rieti train station, I blushed an even deeper red. We still had a fair distance to descend, and this certainly put them on the spot. They didn’t look like it was their kind of thing, and I was pretty sure they wouldn’t have offered on their own. Some Swiss like their Ausländer, but others don’t. There were political parties that wanted to kick all of us out, and their membership came mostly from the mountain cantons.

A quick discussion between them and the van driver dove immediately into the deepest Schwyzerdüüütsch: I couldn’t understand a word of it. But after a bit of back-and-forth, the husband turned to me and made the offer himself, very stiffly, in Swiss-accented Hochdeutsch. I nodded gratefully and said Danke, at this point the only German word left to me.

We clanked into the Tierfed station and got out. I thanked the van driver and trailed the couple to their car, a big square Mercedes. Gingerly I got in the back seat. The husband drove us down the curving road in a dead silence.

There were so many things I wanted to say, stuck on the tip of my German tongue. Your country is so beautiful. I love the Alps. I’m only going to be here another few months, and I want to see everything before I go. Your transport system is really quite amazing. Although the bus component in this case has let us all down, forcing me to ask for your assistance. A helicopter almost chopped my head off at lunch. It chased me. I’m also scared of tunnels. I thought that VW van in the tunnel was a tram that was going to squish me like a bug. Even without that I was unhappy. I’m sorry you’ve been forced to do me this favor. I hope I don’t smell too much, but I was terrified twice today. That rarely happens even once. If it weren’t for the kindness of Swiss women I wouldn’t even be here. Your farm wives are so nice. But a lot of you are mean to hitchhikers. And your cable cars stop way too soon in the day. I think a lot of you must have been traumatized by the Böögen, wouldn’t you agree? It’s a Swiss theory. It explains a lot, you have to admit.

I said nothing;. None of it was sayable. I could hear the sentences in a sort-of German in my mind, but I could not make my mouth say them.

In the front seat they were just as quiet. It was too bad, really; we had just spent the day up there in the same mountains, after all. I focused my mind, ignored my insecurity about tense and word choice and sentence order, about whether it would properly be wohin or woher, tag or morgen, die or der or das. . . . I had made so many mistakes. How do you play baseball? You take nine human beings. . . . my teacher had grinned at that one, he couldn’t help himself. But if you got your meaning across, Mario had said, that’s all that matters.

Where to today did you wander?

Rüchi, the wife replied.

Rüchi! The mountain?

Yes, the mountain. Rüchi is a mountain.

It was the peak at the end of the question mark, one of those looming over the Muttseehutte.

Wow, I said.

They had gone up there for lunch, she explained.

I got out my topo map, and she twisted around to show me their route. From the cable car they had traversed the Muttenwandli—then climbed the south slope of the Nüschenstock at the end of the question mark—then run the ridge from there up to Rüchi. Ah genau, I said as she named every point, genau. Exactly. This was what my Swiss teammates always said when other people were telling them things. It was something like our uh huh, or I see, or yeah yeah, or you bet. Genau: it’s a word the Swiss love to say and to hear. It may be the national anthem all by itself.

Pretty? I asked, being careful not to say Already?

They both nodded. Very pretty, the wife said.

Then she said, And where did you go?

Kistenpass.

Keesh-tee-pahsss!

That must be what one always said. Some kind of surprise about it. Well, maybe so. Yes, I said. Keee-stee-pahss.

And was it pretty?

Very pretty. The Alps, I said, are very, very pretty.

They nodded again, glowing with quiet pride, with love. Genau, the husband murmured.

#

The train for Zieglebrücke was leaving when I walked in the station, and in Zieglebrücke I had to run to catch the Zürich train. My legs were sore. On the Züri train I relaxed. I was going to make it home that night. Zürichsee, Hauptbahnhof, a number Six tram; up the hill, up the stairs, into our apartment, flop into my kitchen chair. It was 7:15 P.M.

“How was it?” Lisa asked. “You look kind of wasted.”

I opened my mouth, but nothing came out. I gaped like a goldfish.

She pointed a spatula at me. “Did you have another adventure?”

“Genau.”

Post a comment on this essay.

About the Author

"Bio: I am a science fiction writer, I live in Davis. Not much more to report. Oh, if you Google Earth my hike and click on the photo pop-ups near the Muttsee, there is a photo of the helicopter. Amazing."

More info:

Kim Stanley Robinson in Wikipedia.