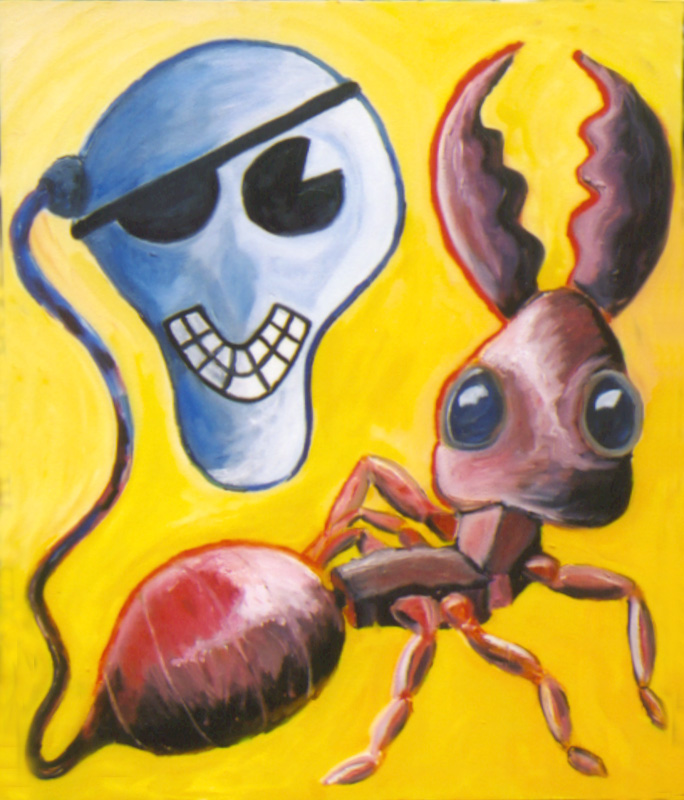

Strategy for Conflict Avoidance:

Memo to the Commander-in-Chief

by Michael Blumlein

Dear Chief,

If you watch an animal long enough, it’s going to fornicate. This is a scientific fact, and it was reinforced to me one night while I was observing two small ants in a bird’s nest I had found that day. The nest was beside the road, wedged in the crotch of some intersecting willow branches. It was soggy from a recent rain but otherwise intact. It looked quite sturdy and strong. I was tempted to take it home for my collection. I weighed the pros and cons of taking something that might still be in use, and then I did take it. This was my reasoning: sitting there so close to the road, the nest was in a risky spot. Not everyone’s a careful driver, and even the careful ones have bad days. I was protecting the young of whatever bird used that nest from falling out and getting hit, and besides, there was no saying that, using it once, the bird would use it again. Some birds build new nests every year. I was doing a good deed for that bird, a service, a protective service. I was being a good citizen, not one of those guys who goes around randomly stealing nests. The ants were in the cup part of the nest, the inside concave part, on a minuscule stick beside a little leaf. When I first looked at the nest, I didn’t see them.

They were there, but since I didn’t expect them, I didn’t see them. I had just finished examining the skull of what I believed to be a cormorant, which I’d found the day before, along with the rest of its skeleton, on a promontory jutting out into the bay where I was staying. There were other remains and partial remains of birds on that spit of land, smallish birds that were prey to the kites and hawks that patrolled that area, but the cormorant had not been eaten by a bird. Its body was intact, and cormorants, as far as I knew, had no avian predators. It had died some other way, and I was left to wonder what that way was. High on that bluff, surrounded by bushes and grass, seemed a strange place for a cormorant to be. I’d only ever seen them flying like ducks above the water or perched on rocks beside or in the ocean. I wondered if the cormorant was old and had lost its eyesight. I wondered if it had got confused and had flown one way when it should have flown another. I wondered if it had been carried there. I wondered if it was like an elephant and had gone there on purpose to die. I wondered all sorts of things, but I had no answers, by which I mean that all my answers were speculation. Later on, back home, when I held the skull in my hands and examined its shape and form, I had other questions, but these I was better able to answer. Why? Because I’m a bone man; I have a love of bones. The tiny brain cavity; the huge eye sockets, each nearly as big as the brain itself; the grooves for nerves and arteries; the sinus cavities to make the skull lighter; the skinny jaw, too thin to support any but the smallest, most compact muscles, just enough muscle to generate the force for the cormorant to open and close its beak, not near enough for it to chew. Which was a good thing, seeing as it had no teeth, at which point I recalled having seen an arctic loon swallow a herring whole that very morning, and then I remembered that cormorants were used by fishermen to catch fish, which wouldn’t work very well if they chewed them first, so that was another good thing about the absent teeth. I really liked studying the skull and figuring out how it all held together and how everything worked. It seemed so beautiful and economical and perfect to me, which made up for the slightly spooky feeling I had of holding what used to be a living thing in my hands, and not just any part of this living thing, but the head, the thinking part, the conscious part, the part where I located, for no particular reason and only if there were such a thing, the cormorant’s spirit. I wanted to be at peace with that spirit. I would like to be at peace with all spirits, not just the cormorant’s but the spirit of the bird whose nest I’d robbed, and ants I’d killed either deliberately or inadvertently, and people I’d wished bad things about or for. I thought of saying a prayer for peace. I didn’t then, but I’ll say it now. I love you, cormorant. You’re beautiful to me. I love your big eyes, they remind me of the saucer eyes of young children. Please don’t hurt me. Either in my dreams or when I’m awake. Don’t come alive and bite me or peck me or nip me. Don’t take revenge. I mean no disrespect to you. If it’s any consolation, I have other skulls. Will it help if I promise to will my own skull, when I die that is, to science?

First a riddle, then an anatomy lesson, then a prayer...the skull of the cormorant was like a mantra to me, it was like a match, a tiny flame that led to a hot and welcome blaze. Compared to it, the fist-sized, damp and dirty-colored nest of sticks and leaves and duff seemed dull. Which is why I didn’t see the ants. Or the baby sow bug or the tiny leaf eater. Or, for that matter, the third ant, who seemed oddly disinterested in the other two.

The pair of ants seemed linked somehow, buddies or something. Chums. Homeboys or maybe homegirls. When I first noticed them, they were scrabbling around kind of aimlessly, then one of them took off with a purpose, like a scout or something, while the other one stayed behind. The scout ant didn’t go very far, or stay away very long, and when it came back, the two of them faced each other, not head to head like dogs but full on, body to body, front to front, claw to claw. Imagine two people touching not just hands but feet, palm to palm and sole to sole. It was like that, and I felt a little like a peeping-tom, like I was spying on something I shouldn’t be, something personal. I thought of lovers rubbing up against each other, and I also thought of best friends giving each other skin, high and low fiving. I’m guessing that the ants were talking, passing information back and forth, and I expected the one who’d stayed behind to take off once it got whatever news the scout ant brought. Which was another mistaken assumption. Just because the homebody ant got information didn’t mean that it would do something about it. Like you say something to someone, a kid or your wife or maybe some associate, you give ‘em a heads-up, say, or some advice, or a stern rebuke, or a warning, it doesn’t mean they’re going to listen. Sometimes the more you talk the less they hear, or maybe they do just the opposite of what you say. So then maybe you try an experiment, you say the opposite of what you want and see what happens. Or maybe you just throw something, level ‘em.

On the other hand, maybe the ant was doing something, it was making a statement, or a point, by staying where it was, which is what it did, just like before. The scout ant took off a second time, and in a minute or two it came back. This time it walked over the back of the stay-behind ant, and then the two of them separated and began gesticulating to each other. It was the same face to face position, only this time they weren’t touching, and then they moved until they were standing side by side. They continued whatever they were saying, legs and claws busy in the air but bodies now butt-down, hunched over at the ant equivalent of a waist. They reminded me of two guys hanging out on a stoop, shooting the breeze. Or two girls at a lunch counter or a park bench, yakking. The stay-behind ant was more reserved than the scout, more economical in its movements, and after awhile the two of them seemed to run out of things to say. First one became still, and then the other one did. They were still for a long time, a very long time, and I wondered if they’d died, perhaps from using up so much energy talking. I read a story once of a man who talked himself to death. It’s in the Guinness Book of Records. He talked for something like two weeks, non-stop, and then he died. It’s listed as a suicide, but maybe he didn’t have a choice. Maybe he couldn’t stop talking, even when he tried. I’ve heard of people like that.

Or maybe the ants weren’t dead, they were just taking a rest. Or waiting for something to get them going again. Some new information from outside, something that only ants would notice. Or something inside, some inner impulse. Like a spark, something to get them jump-started. They looked like bumps on a log, inert, almost mummified, and I asked myself, do ants sleep?

I decided that they do, mainly because when they did start moving again, it looked just like someone waking up. The scout ant was first. It snapped awake as if it had been startled by a loud noise, instantly alert and ready for action. The stay-behind ant woke up slower, bit by bit, as if sleep were some kind of blanket that it had to fight to push off. I found it interesting that two identical-looking ants could have such distinct personalities. I used to think that all of them, all the workers anyway, were alike. But obviously that’s not the case.

As for the fucking, I have to confess I lost track of who was doing what to who. In all honesty I couldn’t see exactly what it was that they were doing, except that one was behind the other and partway up its back, a position in other animals I associate with sex. I know that with most ants it’s just the queen that gets humped, and neither of these looked like a queen, though I’ve since read that in some species the worker females get in on the action too. These particular ants were very small and partially hidden by a leaf, and I had to strain to see them so I couldn’t tell if they were male or female. I couldn’t really tell anything for sure. Maybe if I had the big, fat eyes of a cormorant, I could be more definitive and scientific.

Another option: I could keep the nest in a jar and examine it every day to see if more ants have appeared. If they have, I could say that one of the ants was a fertile female and did have sex, the result of which was babies. (Offspring? Antlings? Whatever.) I could say this, but would I know it? Couldn’t there be other explanations?

Here’s one: God did it. Here’s another. It was the stork. Maybe the babies came from another dimension, or maybe they just materialized -- poof! spontaneous generation -- out of thin air.

And if no babies appeared? Maybe they were dry-humping. Maybe the female was sterile. Maybe the male was shooting blanks. Maybe it wasn’t sex at all.

You can’t make assumptions, that’s all I’m saying. Things are not always the way you think they are, or how you want them to be, or how they seem. You have to open your eyes and keep them open, chief. You have to open your mind. It’s a question of honesty. It’s a matter of respect. We have much to learn. Be kind, be merciful, be strong. By all means. But first, be scientific.

About the Author

Michael Blumlein is a writer and a physician. His most recent novel, The Healer, has been called “a landmark in its genre.” He has been nominated twice for the World Fantasy Award and twice for the Bram Stoker Award. He has written for the stage and for film, and his novel X,Y was made into a movie.