On Saturday, September 22, 2012, I’ll be at the Philip K. Dick Festival on the SFSU campus in south San Francisco. I’m scheduled to give a talk, “Haunted By Phil Dick” at 2 p.m. that day, and I’ll be on a panel with Jonathan Lethem and other Dickians at 5 p.m. as well.

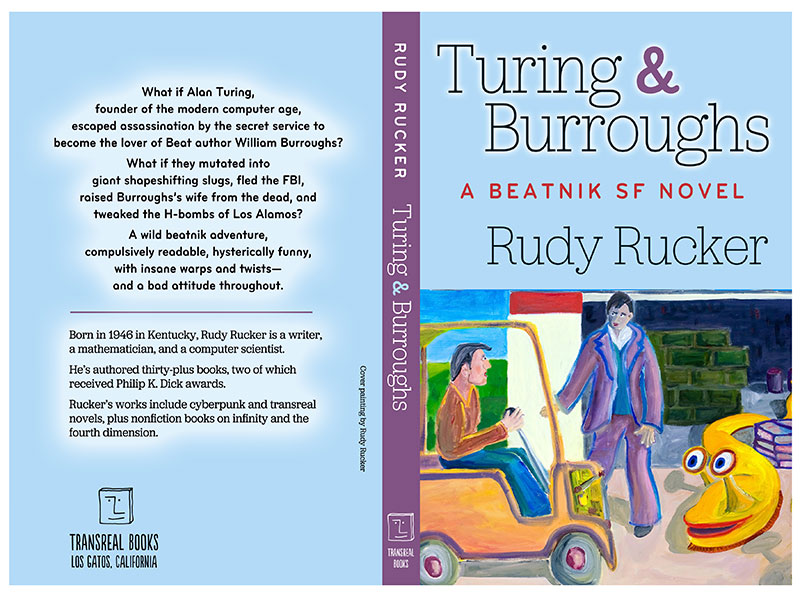

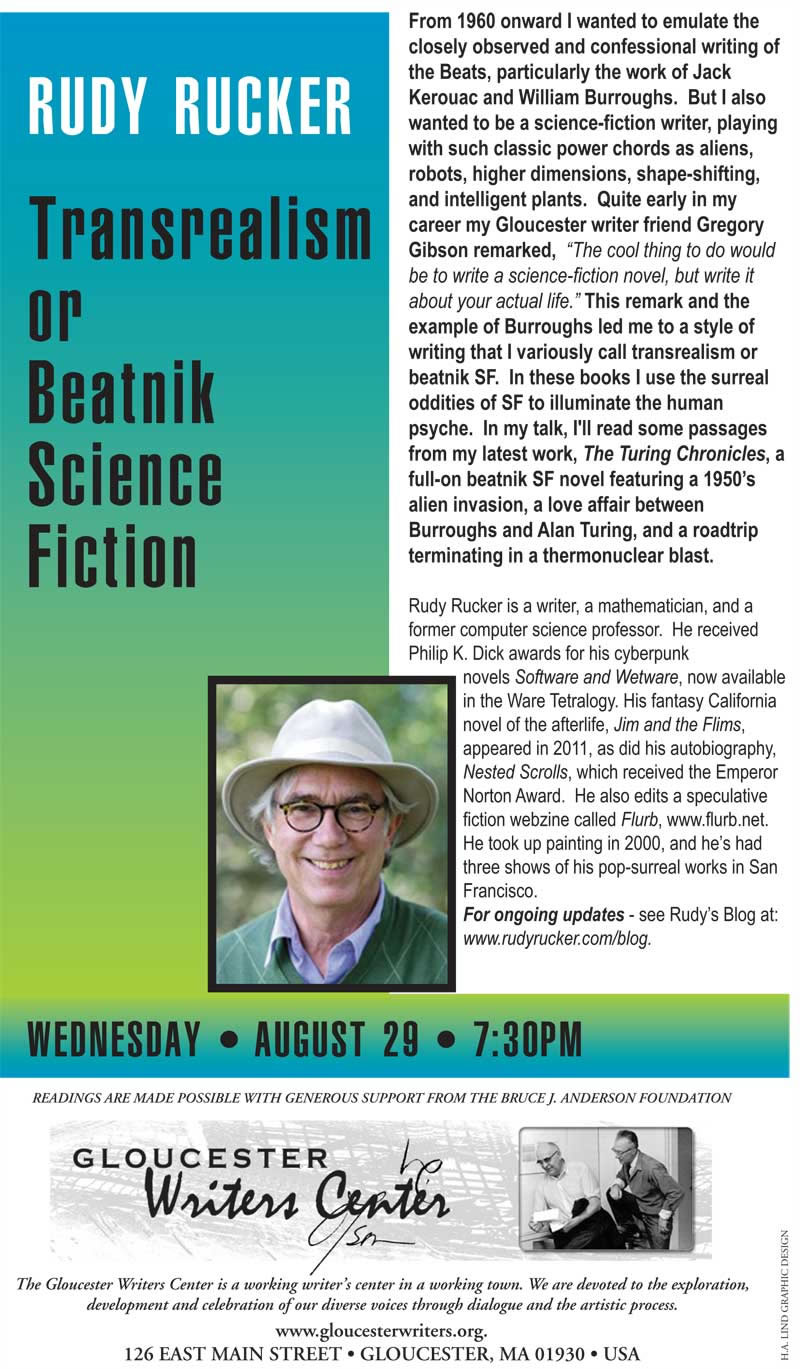

For today’s longish post, we have the text of an email interview about my novel Turing & Burroughs that the young writer Nas Hedron conducted with me from Brazil.

Hedron is the author of the novel Luck & Death which, like my own novel, involves Alan Turing. You can learn more about Hedron via the links on his blog The Turing Centenary, where his interview with me also appears.

Q 1. I wonder if you can set the stage for us with reference to Alan Turing, you, and writing. Who was Alan Turing to you before you wrote Turing & Burroughs: A Beatnik SF Novel? And what gave you the impulse to write your novel about him?

A 1. In the course of getting my Ph.D. in mathematical logic, I learned the technical details of Turing’s theorems about the idealized computers that came to be called Turing machines. I read his epochal 1937 paper “On Computable Numbers” numerous times, and I was struck by the clarity and the depth of his thought.

Being interested in the possibilities of intelligent machines, I also studied Turing’s 1950 paper, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” a non-technical paper in which he proposes the so-called Turing imitation game as a test for true AI: you might say that a program is intelligent if you can’t tell it from a human when you’re exchanging emails with it. It’s worth noting that Turing initially framed his “imitation game” in terms of someone trying to distinguish between a woman and a man.

Later I became interested in using so-called cellular automata programs to simulate the patterns that emerge in the tissues of plants and animals—patterns like the the spots on leopards, the markings on butterfly wings, the zigzags on South Pacific cone shells. This is what Turing was working on near the end of his life. In 1952 he published an amazing paper, “The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis.” In the morphogenesis paper he explains how, by dint of days of hand computation, he emulated a biological cellular automaton process to produce irregular black spots like you might see on the side of a brindle cow.

To me Turing is a heroic and inspiring figure. He worked on deeply fascinating things without getting lost in merely technical mathematics.

The other compelling aspect of the Turing story is that he was openly gay, he was persecuted for it, and that he had a strange and tragic death—which is usually described as a suicide.

Regarding Turing’s death by cyanide poisoning, I’ve always felt there’s a real possibility that he was in fact assassinated by agents of the British government. This seems even likelier now that we know Turing was involved in a top-secret code-breaking effort during World War II. In the 1950s, there was a collective hysteria over the possibility of homosexuals being a security risk.

Before I began contemplating my own novel, I’d read some stories and plays about Turing. But I didn’t feel that any of these works captured the vibrant image of Turing that I wanted to project. There can be a tendency to write about homosexuality in a lugubrious tone—as if a homosexual is a pathetic person who’s afflicted with a lethal disease. But Turing was anything but downcast about his predilections.

A 1 (Continued).

In the spring of 2007, I wrote a short story about Turing, “The Imitation Game.” And this story later came to be the first chapter of my novel. In the short story, Turing escapes being poisoned by British government agents. And to escape, he swaps appearances with his dead male lover. And here comes the science fiction: Turing grows two new faces by using principles that he described in that paper where he generates the shape of a spot on a black-and-white cow.

As sometimes happens to me, I had difficulty in selling my story. Maybe it wasn’t sufficiently solemn and lugubrious—and I was presenting Turing was a gay outsider, heedless of proprieties, and by no means a victim. In any case, in 2008 my story appeared in the British magazine Interzone and in 2010 in The Mammoth Book of Alternate Histories, edited by Ian Watson and Ian Whates.

Early on, I began wondering if there might be some way to expand my Turing story into a novel. At the end of my story, Turing escapes to Tangier, and I formed the notion that he ought to connect with the Beat writer William Burroughs, who was living there at that time. Two brilliant men, gay, outcast—perhaps they’d hit it off.

I’ve been a huge Burroughs fan ever since I first came across an excerpt of Naked Lunch in the beatnik magazine, The Evergreen Review—this would have been back in 1960, when I was fourteen. My big brother had a subscription to the magazine, and I’d leaf through it, looking for smut. Instead I found a literary career.

I particularly admire the irresponsible and laceratingly funny style of the letters Burroughs wrote to his friends from Tangier. And so I decided to write my second Turing story in the form of letters from Burroughs to Kerouac and Ginsberg.

This second story, “Tangier Routines,” was so gleefully scabrous that I didn’t bother sending it to any magazines, science-fictional or otherwise. Instead, in the fall of 2008, I printed it in a webzine Flurb that I’d managed to start. And then in 2010 and 2011, I ran two further Turing & Burroughs stories in Flurb—“The Skug” and “Dispatches From Interzone.”

I was still unsure about how to build my tales into a full novel, but in 2010 I finally read Alan Turing: The Enigma, the wonderful biography by Andrew Hodges, And here I learned that Turing was everything I could have hoped. Stubborn, unrepentant, impulsive, and with a very warm and human personality.

I discovered that, as part of some psychological therapy he was undergoing, Turing himself made a start at writing a transreal speculative novel late in his life—and this allayed any uneasiness I’d felt about dragging his name into the gutter of science-fiction.

So why did I write a beatnik SF novel about Alan Turing? In short, I’d come to think of him as my friend, and I wanted to give his character a cool place to live.

Q 2. What interested you about bringing the mathematician Alan Turing together with the Beat writer William Burroughs?

A 2. To some extent this was a matter of convenience. I needed Turing to flee England in 1954 to escape assassination by the secret service. Even though Turing has changed his face in my novel, it seemed like he’d feel safer taking trains and ferries than in trying to get on a plane.

From my familiarity with Burroughs, I knew that Tangier was an open city at this time, a good place to take refuge—Burroughs often referred to it as Interzone. And, checking my references, I realized that he was indeed living in Tangier at this time.

Having my two heroes meet seemed perfect. Having them connect also solved a problem I was having in figuring out how to write a gay male character in an effective way.

William Burroughs is a queer writer whom I’ve always found easy to identify with. He has an outspoken zest and a defiant rudeness that make it seem cool and reasonable and entirely desirable to be a homosexual heroin addict.

Even though I myself am merely a punk SF writer, I sometimes feel a certain social opprobrium regarding my esoteric interests, and, over the years, I’ve occasionally girded myself by adopting Burroughsian attitudes and mannerisms. Wearing the old master’s character armor.

One of the challenges in writing a William Burroughs character was that I had to deal with the fact that, a couple of years before the start of my novel, Burroughs had shot and killed his wife Joan in Mexico City. At first I felt like this was too explosive and difficult to write about directly. But then I realized that I had to face the killing.

So my Turing and Burroughs end up going to to Mexico City, resurrecting Joan, and letting her run a number on Burroughs. I wanted to give Joan a voice, and to give her a chance to get even.

I wrote the Mexico City chapter from the Burroughs point of view, writing very fast. It was like I was possessed—but in a good way. The experience was heavy and ecstatic. For months I’d been anxious about writing the chapter, and all at once it was done

I’m always happy when I’m being Bill Burroughs. He didn’t give a f*ck what people think. And neither did Alan Turing.

Q 3. Its impossible to read Turing & Burroughs without comparing and contrasting Turing’s real life with his life in your novel. Two of the simplest ways in which one might develop a story about an outsider’s relationship with the world are victory and defeat. In a victory story, the outsider transforms the world into something more congenial; in a defeat story, the world crushes the outsider.

In Turing’s real life, defeat was the way things played out. But throughout much of The Turing Chronicles, it looks as though Turing is headed for victory or at least for a rapprochement. He and his allies are turning everyone into shapeshifting mutants like themselves—what you call “skuggers.” But then, at the end of your novel, you return to something closer to Turing’s real life, something like defeat. Your Turing character saves the world, and he dies. Did you plan this in advance?

A 3. That’s a very interesting question, and I hadn’t thought about this so clearly before.

I’ve always been piqued and annoyed by the defeat aspect of Turing’s actual life. Either he was goaded into suicide or he was murdered outright. So, as I mentioned before, In writing Turing & Burroughs: A Beatnik SF Novel, I wanted to create a world in which Turing escapes his tragic fate and lives on to have wonderful adventures.

But I knew from the start of my novel that, even though my Turing character has escaped England, he’s a marked man. The pigs, the bullies, the scumbag straight-arrows—they’re unrelenting in their efforts to bring down our Alan. So my novel takes on the quality of a long chase.

It would have been possible, at least in principle, to write a novel in which Turing manages to convert everyone in the world into a shapeshifting skugger like himself. But fairly early on, we begin to understand that this wouldn’t be a pleasant endpoint to reach. We want to be ordinary humans, not skuggers.

So I needed for Turing to somehow undo the mutations—but without killing off all the people who’d become skuggers. And this wasn’t going to be easy, with the cops and feds breathing down his neck. So before long, Turing was heading towards a world-redeeming self-sacrifice. But this felt like the most dramatic way to go. Turing as Savior. It’s a big, strong ending.

I think one can argue that Turing doesn’t truly suffer defeat here. He transcends. As the Beat writer Jack Kerouac would put it, Alan ends up safe in heaven dead. And in the context of my novel’s world, heaven is a real place.

Q 4. In Turing & Burroughs, Turing experiments with what one might call computational human flesh. This bears a certain family resemblance to “flickercladding,” the soft robot flesh you imagined in the Ware Tetralogy, in which each grain of the cladding acts as a processing unit. This particular feature of your work puts me in mind of the effects that director David Cronenberg uses in his movie version of Naked Lunch—I’m thinking of his Burroughs character’s soft, genitalia-like typewriters. Are you conscious of a reason why you like conflating computation and flesh?

A 4. I’ve always been bored by the idea of rigid, clunky, machine-like robots. I wanted robots to be funky and wiggly and sexy. I think it’s likely that if we ever have really useful and intelligent robots, they’re going to be more like tentacled octopi than like brittle ants. Of course thirty years ago, when I started writing about flickercladding and piezoplastic “moldie” robots in my Ware novels, this wasn’t at all a familiar idea.

Having gotten used to the idea of soft machines, it became natural for me to turn things around—and to have the cellular structure of human flesh become as malleable as the material of a computer display.

In my Ware novels there’s a drug called “merge” that lets people melt together inside a tub called a love puddle. And in Turing & Burroughs, a person who’s a skugger can turn into something like giant slug. There’s a scene where Turing and another skugger have sex by twisting themselves around each other while hanging from a rafter at Burroughs’s parents’ house. Mrs. Burroughs throws them out.

Reading a draft of Turing & Burroughs, my wife said, “Oh, you’re always doing this, having people merge together, it’s so icky.” And I’m like, “Yeah, but that’s sex, isn’t it? That’s how it is.”

We’re biological organisms—we’re not computers, and we’re not machines.

A 5. In your free downloadable book-length Notes for the Turing & Burroughs novel, you mentioned the possibility of having J. Edgar Hoover be a character. I’m a little disappointed that he didn’t make it into the book. I had a hankering to see Turing and Hoover go head to head. What kinds of considerations are important in making decisions about what to leave out and what to put in?

A 5. My sense was that I didn’t want to put too many famous people into my book. If you overdo that, then you’re name-checking, and it gets to be like a bus tour of the homes of the stars. And the stars dazzle away the reality of the characters whose lives you want to delve into.

If I am going to recreate a historical character, I want it to be an interesting person whom I like. And for sure that’s not J. Edgar Hoover! He’s a dead horse. Just because I write something in my notes for my novels, doesn’t mean I’m really serious about using it. Often in my notes I’m just killing time and goofing around. Waiting for the Muse.

Given that I had Burroughs and Turing in my novel, I did feel that I ought to bring in some other Beats and at least one other scientist. I went for Allen Ginsberg, Neal Cassady, and the mathematician Stanislaw Ulam.

Ulam isn’t too well known, but he did a lot of fascinating things. He helped invent the hydrogen bomb, he wrote some of the first interesting computer programs, and he worked with lava-lamp-like continuous cellular automata. His friends thought he was too scattered, too much of a playboy. My kind of guy.

I was happy to have Ginsberg and Cassady show up in a Cadillac. My friend Gregory Gibson read a draft of the novel and he said that scene was like in a circus when you see the wild clowns getting out of a car.

I held back from putting Kerouac into Turing & Burroughs, as Jack would have been too much. He would have taken over. Remember that the main Beat I wanted to write about was William Burroughs.

When I was in the middle of writing the novel, I happened to see some video footage of Burroughs at his house in Lawrence, Kansas, taken a year or two before he died. And I knew right away I could use this scenario for the last chapter of my book. So the last chapter is set as a transcript of Burroughs talking to a video camera.

“And now I’m turning off the machine.”

That’s the book’s last sentence, with Burroughs talking. I like that ending. You might say that it captures the theme of the book.

You can turn off the machines and get wiggly. Even if you’re Alan Turing. Long may he wave.

[Curious? Go to Transreal Books or try browsing free sample version of Turing & Burroughs online as a webpage.]