Munich is such a beautiful city. Lots of buildings were bombed in the war, but the Germans have restored it out the wazoo. In spots, Munich is almost like a theme park, although even the new things are build from solid metal and stone. Things are solid and well-proportioned, with lots of trees.

Since I was alone in Munich for much of time time, I wrote more notes and took more pix than in the other spots, so I’ll break this material into several posts, with the tense somewhat randomly oscillating between present and past—which is, I suppose, vaguely appropriate.

The Theatinerkirche in the downtown (in the right on the picture above) was pretty much reduced to rubble, but the Germans put it back the way it used to be.

The Altes Rathaus (old town hall) got destroyed, and was rebuilt in a fairly ugly way, but there’s a gothic-looking Neue Rathaus (new town hall) from 1908 (shown on the left above) that’s pretty cool, although my cousin Rudolf says it’s kitsch in that it imitates being medieval Gothic.

The Altes Rathaus has some wonderful wrought iron, I liked the fairytale-border-illo quality of that frog shown above.

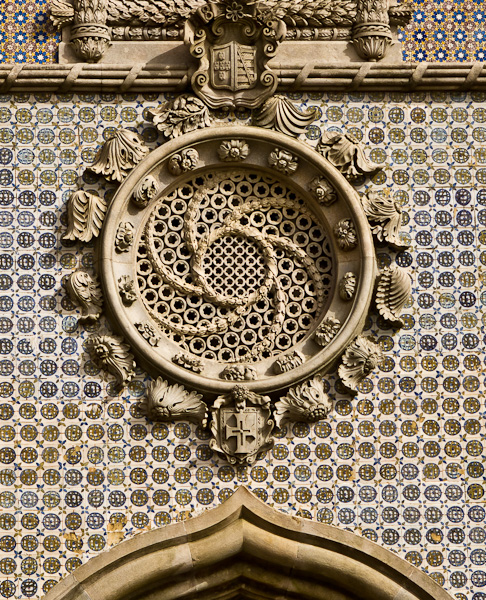

And there’s some great old Jugendstil (that is, German Art Nouveau,) buildings as well.

The apartment block where my cousin Rudolf lives with his family on the fourth floor is Jugendstil, and there’s a cute carved bear on newel post at the bottom of the well-waxed flights of walk-up stairs. Very 1910.

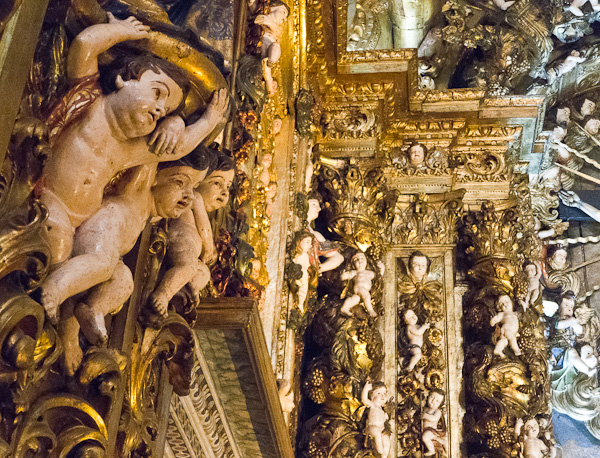

Some amazing buildings in Munich are relatively uncelebrated like, for instance, the Jugendstil lecture hall at the Leopold Maxmillian University. And, like I say, there’s a bunch of amazing Jugendstil houses around, too. I love that stuff. Will we ever find our way back to the wonders of heavily ornamented architecture? Or are we stuck with cheap-ass blank walls for the rest of time?

I’m half-German—my mother was the sister of my Cousin Rudolf’s father. Not that they bore any resemblance to this cartoony old painting of a mermaid and merman.

My cousin Rudolf von Bitter is a smart guy. He’s an author in his own right, with quite a few books—this link searches German Amazon, with a couple of mine sneaking in. He organizes author videos for the Bavarian TV channel. He also has a LiteraVideo webpage with some quirky authorial videos that he’s made on his own.

He drives a beat-up old-style VW beetle, he sought out one made in Mexico for the authentic old-school look. I called it a dreckige Käfer (dirty beetle.) His manner of talking shares a quality of Bruce Sterling’s—you can never quite tell when he’s being sarcastic. We were making dinner plans, and he exclaimed, “Schweinebraten um sechs!” (Roast pork at six o’clock!) I kind of thought he was mocking the eating habits of the average German, but that night he did in fact order Schweinebraten, albeit at seven. He does it, but he mocks it at the same time.

It was good sitting with Rudolf’s family, enjoying the glow of their home, and listening to them, sharing food.

A restaurant where we ate together had a life-sized bronze sculpture of a pig outside. I posed with it, and a drunk Bavarian smoking outside the restaurant said to me, “Schweine gehören zusammen.” (“Pigs belong together.”) But I’m not going to run the picture of me with the bronze pig. Instead here I am with one of Christina’s sculptures.

I’m referring to Rudolf’s wife Christina von Bitter . She’s a wonderful artist—she makes sculptures of whimsical large constructions from wire, paper and paste, some pink, but mostly white.

[My mother, Marianne von Bitter, in 1936.]

Rudolf’s two children are very well-bred and pleasant. His 17-year-old daughter looks a little like my mother looks in a photo taken when she was about 20. There’s a certain shape of nose that my mother and I and Cousin Rudolf have, the von Bitter nose, and I see a little of that in Rudolf’s daughter. And there’s some similarity in their brows. How touching to come back to Germany and find an echo of Mom. It’s touching and a bit uncanny.

One of Rudolf’s neighbors puts a special New Year’s inscription in chalk on their door every year, I saw a few more of these around town. They have to do with Epiphany, the Feast of the Kings. The letters stand for Caspar, Melchior, and Balthazar—the names of the kings.

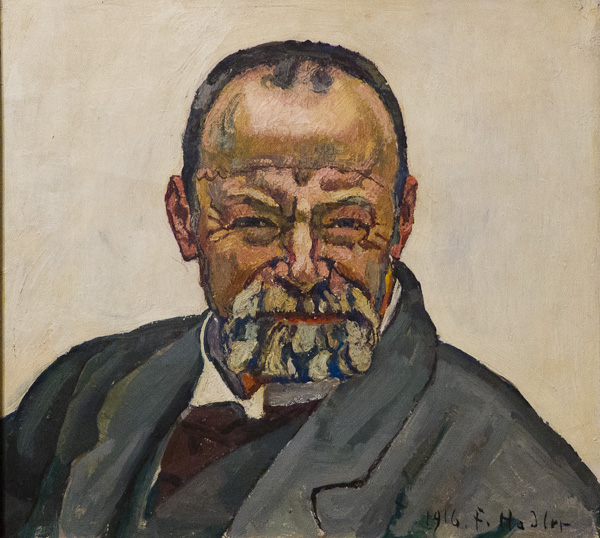

[Hans Cranach the Elder, “The Mouth of Truth” (If you tell a lie, it bites your hand)]

Unlike me, cousin Rudolf has actually read the whole of The Phenomenology of the Mind by our common great-great-great-grandfather Georg Hegel. He advised me on a tactic for finally plowing through it. “Read it like a novel. Even better, follow the advice of the Hegel scholar Ernst Bloch, and read the Phenomenology in parallel with Goethe’s Faust.”

By the way, here’s a zoomable PDF of our shared family tree, which was made up by our common uncle, also a Rudolf von Bitter, who died young in WWII. You read it in reverse, that is, Uncle Rudolf is at the top, and his ancestors are futher down. My name is Rudolf von Bitter Rucker, you understand. So cousin Rudolf and I would be one step furthere above the top of our uncle’s family tree. You can find Hegel down there among the ancestors.

Rudolf and his wife Christina and their two children were about to drive to Italy for a family vacation—it’s an eight to ten hour drive. They like to listen to an audio books on CDs during these long drives to pass the time. Christina had considered getting Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, but instead had gotten an Agatha Christie novel (in German). And Rudolf exclaims, “No, I have gotten CDs of Franz Kafka’s Der Prozess. It’s really very funny.”

Although I was in fact sympathetic to Rudolf’s proposal, at the same time it’s incongruity cracked me up, it was like something a Woody Allen character would do—“Uh, yeah, I like to play a tape of Kafka’s The Trial when I’m a long trip with my family.” Rudolf is truly my cousin.

I didn’t make it to the famous Hofbrau Haus this time, although I did swing by an outdoor offshoot of the Hofbrau near a Chinese Tower in the park. A brass band pumps oompah music from two stories up in the tower, and you can buy a soft pretzel the size of a baseball catcher’s face protector.

Munich is Beer City, and it took some effort on my part to maintain a sane frame of mind. I actually saw a group of ten guys pedaling a bar down the street, a man-powered trolley, complete with a giant wooden keg of beer, big steins on the bar-top, and rowdy singing.

I had one non-alcoholic Lowenbrau in a beer garden, just for old times’ sake, but that was enough. For the rest of the time, I stuck to a pleasant drink that Christina von Bitter steered me to: Apfelshorle, which is apple juice with sparkling water mixed in.

I had a pleasant flashback, walking into a museum of crystals run by the geology group at the local university. When we were living in Heidelberg from 1978-1980, there were some displays like that, and I’d look at them while working on an early draft of Infinity and the Mind, my nonfiction book about infinity, and at the same time writing White Light, my novel about a guy who climbs to higher of levels of infinity in the afterworld. Each endeavor was feeding the other. And those crystals came to seem like symbols to me, and I dreamed about them. Here’s a quote about this from my forthcoming memoir, Nested Scrolls: The Autobiography of Rudolf von Bitter Rucker.

I got into a very pleasant and exalted mental state during this period of time. I remember having a magical dream in which I was scrambling up the ridge of a mountain. The stone underfoot was slippery pieces of shale, and among the stones I was finding wonderful polyhedral crystals the size of chestnuts or hedgehogs. Even within the dream, I knew that these treasures represented my wonderful new ideas.

I liked seeing German words written out everywhere, I might smile at odd German surnames I spot, such as “Pfnür,” which sounds a bit like my SF word, “fnoor”. It’s great hearing German spoken aloud. My Muttersprache, the mother tongue. Everything sounds somewhat funny to me in German. At one point I heard a woman complaining about an acquaintance. “Die blöde Kuh! Sie ruft mich ewig an.” (“The stupid cow. She’s always phoning me.”) Love it.

I’d almost forgotten that I can speak German, but the skill comes back quickly. It’s like remembering you can ride a bicycle. One thing I always need to remember is that I have to push the accent so hard that, from the inside, it feels like I’m straining and overdoing it. But if I don’t make that extra effort, nobody can understand me. Certainly the locals treat me better if I try. They think it’s cute to hear an American talk half-decent German. Like seeing a dog walk on his hind legs.

The working-class locals—the echt Bavarians—have a cozy way of rolling their R’s. But my cousin Rudolf and his family speak the standard, less-accented German, the so-called hoch Deutsch.

After Rudolf and his family left for their trip, I was my own for a few days, into my own head, which was fun, although at times a little lonely. I was definitely slowing down. Like a clock winding down. My legs were beyond tired after two weeks of vacationing. So I spend a lot of time sitting down in cafes.

In the mornings I lie on Rudolf’s couch for awhile. When I’m motionless, it feels so good that it’s hard to get up. Sitting with my legs crossed is an active sensual pleasure. I’m at a point where every day I want to walk a little less. So when I go out, I sometimes ride Rudolf’s bicycle.

But it’s good to get out. I saw five or six guys surfing on a standing wave where a piped surge of water flows out into a park meadow, an artificial stream called the Ice Canal. It’s next to a bridge, and a big crowd was watching. Each guy would manage a minute or two on the wobbly wave, then eat it and get swept downstream. Surf München!

I feel like I’m having an extra inning of vacation here, a bonus round. Listening to an ensemble of classical musicians on the street, complete with grand piano. I start thinking about my life, and again about the Nested Scrolls autobiography I wrote, and about how much better things have turned out for me than I’d ever hoped.

The sweet music fills my throat.