July 9, 2011

I’ve been working full-bore on Turing & Burroughs for a little over a year now. As of yesterday, my novel file is finally longer than my Notes file! 81,621 words in the Novel file versus 80,750 words in the Notes. A turning point. Although the Notes could yet pull ahead again.

I’m on the train, going up to San Francisco for a night today, seeing John Shirley read tonight, and reading at Borderlands tomorrow. Will bring the laptop and keep the fire going. I’ll sleep at my son’s house in Berkeley, even though he and the family won’t be there tonight.

July 10, 2011.

In the morning, alone in Rudy Jr.’s house, I did some work on the novel and essentially finished it.

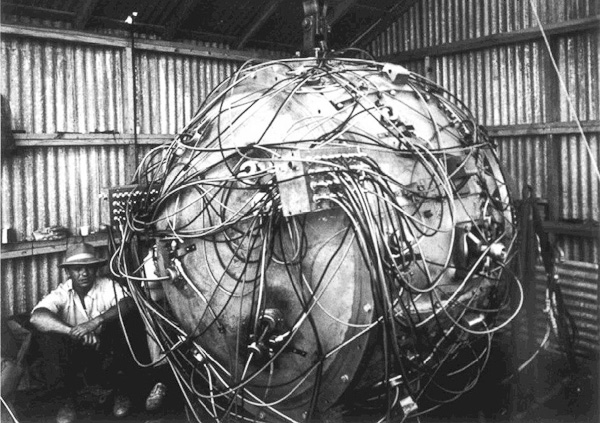

First I had a false-start idea for Chap 17: V-bomb. But I realized that wouldn’t work. Too complicated. So I made it simpler. It’s all about simplification near the end.

I wrote the V-bomb chapter right through to the ending. Hooray! I’m almost done. I just have to add Chap 18: “Last Words,” supposedly by William Burroughs. I was really happy at this point. I walked to the BART stop and a homeless guy looked at me and said, “You the happiest man I see today!” And he was right, I was grinning, aglow, joyful.

One more thought I had later that day: For Alan to effectively modulate the V-rays, and to not hamper the explosion, he should dematerialize into matter-waves right before the explosion.

In the afternoon, I was hanging out on Valencia Street in SF with my artist friend Paul Mavrides, telling him about the plot of my novel, and about the last scene I’d just written and about my recently conceived tweak. Paul was laughing in a friendly way. “So that’s the perfect way for you to distribute your ideas from now on. Dematerialize into matter waves and modulate the V-rays.”

July 11, 2011.

Okay, tonight I wrote “Last Words,” the last little chapter of The Turng Chronicles. I was sitting in my California-Craftsman-style La-Z-Boy recliner armchair in the living-room with Sylvia reading on the couch. The book’s first draft is done. Calloo, Callay!

July 12, 2011.

On the morning of July 12, I lay out on my yoga mat in the back yard and marked up the last two chapters two times, retyped them twice, then went over the final chapter onscreen one more time. And fixed a last To Do item. I think it really is done now, although of course I’ll reprint the final chapter one or more times.

And then I’ll have to do the whole book printout and the full revision thing. But for now it’s good enough to mail to an editor. Over 85,000 words, as planned. I wrote nearly 4,000 words in three days. Yeah, baby.

Finis coronat opus.