Where do I get my ideas for science fiction?

This continues my earlier post on the topic. The material is taken from interviews.

That 3d plastic slug was 3d printed for me by Chuck Shotton.

Interviewed by Heath Row for The National Fantasy Fan, July, 2009. New York.

You asked how I between the value of expanding my consciousness by getting high verse the risks of excess. Ever since I turned fifty, I strike the balance by being clean and sober! When I was younger, like so many writers, I liked to think that getting high gave me creative inspiration—and maybe, now and then, it did. At the very least, it brought me into contact with some colorful people. But at some point, the cost began seeming too steep.

What I’ve found over the recent years is that I don’t actually need any kind of chemical input in order to have strange ideas. Come to think of it, I even had unusual ideas when I was an kid. That’s just how my mind happens to work—you might say that I’m lucky.

These days if I feel dry or uncreative, it helps to simply do something different. Go on a bike ride, go to the beach, see a movie, talk to people or, if I have the time and the money, take a vacation trip. And even if I don’t do anything much, in a day or two the images and ideas come dripping back in. Sometimes it just takes a little patience. So far, the Muse keeps showing up.

Interviewed by Maximus Kim for 3 AM Webzine, November, 2010, Los Angeles

I was a big fan of pot when I was younger. But over time, pot and alcohol got to be more trouble than they were worth, and I got some help and managed to quit using them.

I was rarely high when I was writing—it tended to make the writing seem too hard. But there were times when I might pencil in some revisions while I was high. Or I’d jot down some ideas about my work in progress, if I was high at a concert or walking in the woods, ideas for wacky dialog or bizarre turns of my plot. I’d write them on the piece of paper that I always carry in my back pocket. Some of these ideas would be good, some not.

Artists sometimes fear that they’ll lose their inspiration or their edge if they sober up. And I worried a little about that. But over the years since I quit, I’ve found that I’m just as wild as ever. The weird ideas percolate naturally out of my mind. It was me all along.

The upside of being sober is that I have more energy than before. And I’m much less likely to get into depression and remorse. But I still worry a lot more than I’d like to. That’s how I am.

***

Although I have a Ph. D. in mathematics, I never took a course in computer science or in writing. So I am in many ways self-taught.

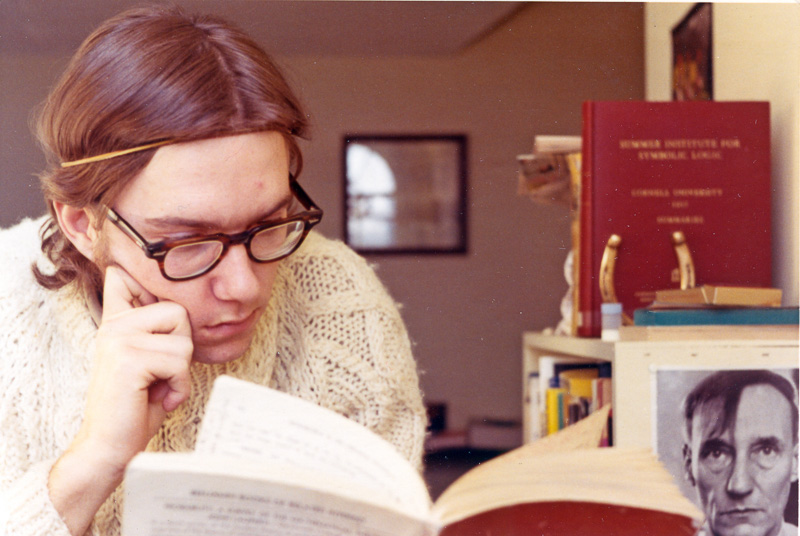

Writing was the craft I wanted to learn the most, and I got my first start at it simply by writing a lot of letters to my college friends. I used a typewriter, just as I imagined professional writers would do. I had an Olivetti portable. Later, after grad school, I got a rose-colored IBM Selectric, a lovely machine, currently enshrined in my basement.

Part of learning to write is a matter of learning to imitate the writers that you admire. I read a lot, and, over the years I imitated Hemingway, Kerouac, Terry Southern, Pynchon, Burroughs, Vonnegut, Phil Dick, Robert Sheckley and many others. Thanks to some fortunate fluke of my mental makeup—and to years of practice—I find it fairly easy to mold words into patterns that I like.

If you read a lot, you develop a large inner library of words and phrases that you love, not to mention a repertoire of story twists, attitudes, and styles of thought. The inside of a working writer’s head is like the backstage wardrobe room at a theater. In your apprenticeship you stock the wardrobe room, then you began assembling costumes from it, and perhaps at some point you’re designing entirely new garments of your own.

We place the greatest value on the things we discover ourselves. School is really a matter of teaching you how to go about your investigations. The real knowledge consists of the things you find on your own.

***

It’s not a good idea to lean too heavily on existing SF books and movies. Those are a pool of old ideas. For the new ideas, you need to look at the actual world. Pay attention to the things you see in your daily life, and the things you see in the media. If you notice something odd, imagine dialing up the oddity to a still higher level.

It’s also good to let go of logic. SF stories are in some ways like fairy tales. Go ahead with any weird, surrealist notion that you have. You can always invent some bogus scientific justification later on!

***

It goes without saying that science needs to push even harder on the problem of finding non-polluting sources for energy. It still could be that there’s some wholly new kind of energy source we’ve never thought of—perhaps something involving dark matter, string theory or quantum foam. After all, two centuries ago, nobody knew about nuclear power or even electricity.

Biotech or genomics seem like huge new frontiers for science. Just as computer chips have replaced gears, I see tweaked organisms of the future replacing chips. In five hundred years we may not have any machines at all. Everything around us will be, at some low level, alive.

Interviewed by Eduardo Almiñana, for Androide magazine, October 2011, Valencia, Spain.

It’s not a good idea to lean too heavily on existing SF books and movies. Those are a pool of old ideas. For the new ideas, you need to look at the actual world. Pay attention to the things you see in your daily life, and the things you see in the media. If you notice something odd, imagine dialing up the oddity to a still higher level.

I’ll never stop being a cyberpunk, not that it’s a commercially viable label to use anymore. We started writing cyberpunk because we had a really strong discontent with the status quo in science fiction, and with the state of human society at large.

Two big thematic notions in cyberpunk are, firstly, the blending of human minds with machines, and, secondly, our psychic migration from physical reality into a web-based virtual reality.

Mainstream thinkers still don’t seem comfortable with the notion that digital reality and mental reality are points on a continuum. Another cyberpunk teaching that’s not so widely known is that digital things can be squishy, funky, and smooth. Like my moldie robots in Freeware that are made of soft, flickering plastic that’s infested with smelly mold.

It’s also good to let go of logic. SF stories are in some ways like fairy tales. Go ahead with any weird, surrealist notion that you have. You can always invent some bogus scientific justification later on!

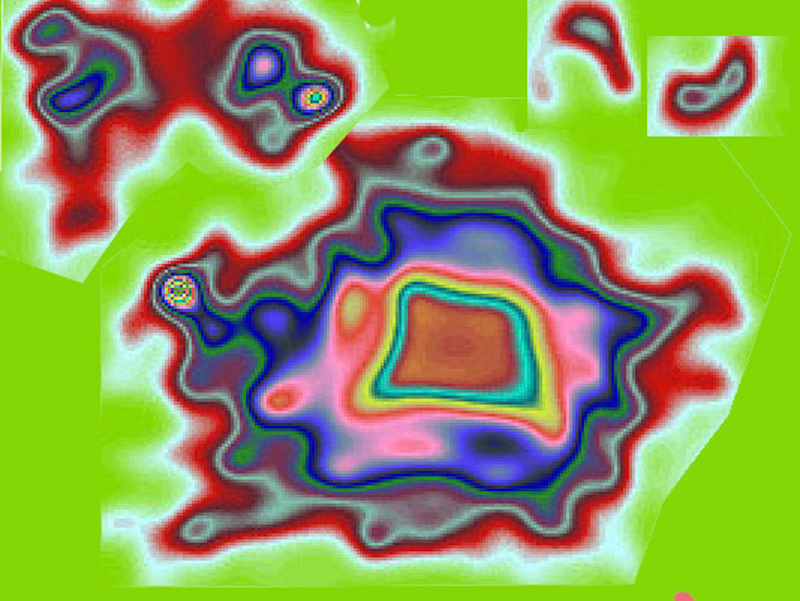

I got into chaos theory when I helped write a popular science software package that was meant to accompany James Gleick’s book Chaos. I think the fundamental insight is that you can have a completely deterministic system that, over time, generates outputs that appear really intricate, complex, and gnarly. People used to suppose that if something was orderly and logical, it would have to be boring and predictable. And that anything really interesting would have to involve randomness. But the chaotic zone lies in between the two. The secret is that if a computation takes a considerable amount of time to run, then its output can seem completely surprising—because you can’t mentally carry out that amount of computation in a tractable amount of time.

***

I never really understood the ideas in economics, in fact I almost failed to graduate from college because I couldn’t stand going to economics lectures. Hate, hate, hate the stuff. It’s like studying Bible stories or pseudoscience—economics has so little connection to daily reality. For instance, it’s completely obvious that companies can’t in fact grow forever, year after year, without hitting some debilitating limits. But the so-called value of a company is based on how much they grow from quarter to quarter. Economics as practiced by bankers is complete horseshit, but they’ve bought out all the politicians, so nothing reasonable ever gets done. In the long run, of course, the situation will resolve itself. Meanwhile we’re seeing a resurgence of the dystopic SF novel!

Interviewed by Brendan Byrne, for BoingBoing, New York, January, 2012

Although cyberpunk is now viewed as a successful subgenre of SF, it was indeed controversial when we started. But that’s the way we wanted it. If nobody’s pissed off, you’re not trying hard enough.

***

Math is a great source of cool SF ideas. And the style of mathematical thought is good training. Often in math you start out with a particular set of axioms and explore what you can deduce from these laws. Creating an SF world is a similar kind of thought experiment. You make whatever wild and crazy assumptions you like, and then see what follows from them.

But, really, when I’m writing SF, I’m just as likely to work the other way around. That is, I’ll start with some cool kind of special effect—like, let’s say, our Earth unfurling to become an infinite plane—and then I’ll dream up some relatively plausible hole in physics that makes my scenario possible.

If you’re willing to jiggle the laws, you can fit everything together in a logical way—and if you ponder the ensuing logical consequences, you come up with some gnarly extra effects for free.

On the subject of math, it’s also worth mentioning that, culturally speaking, mathematicians are about as close to living and breathing aliens as you’ll ever see. Weirder than stoners, weirder than computer hackers, weirder than SF fans. My people.

***

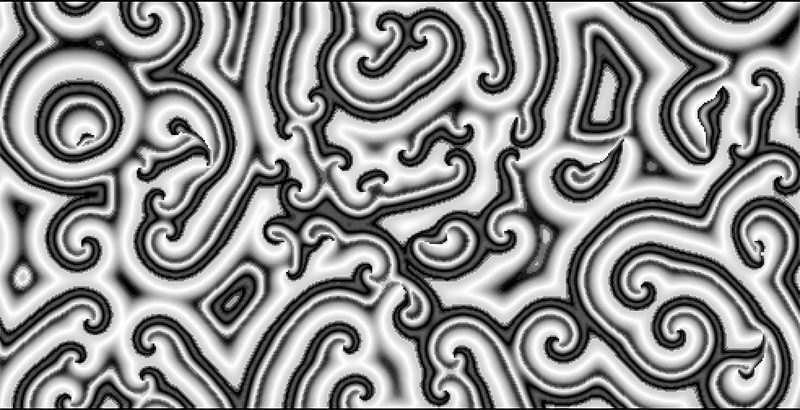

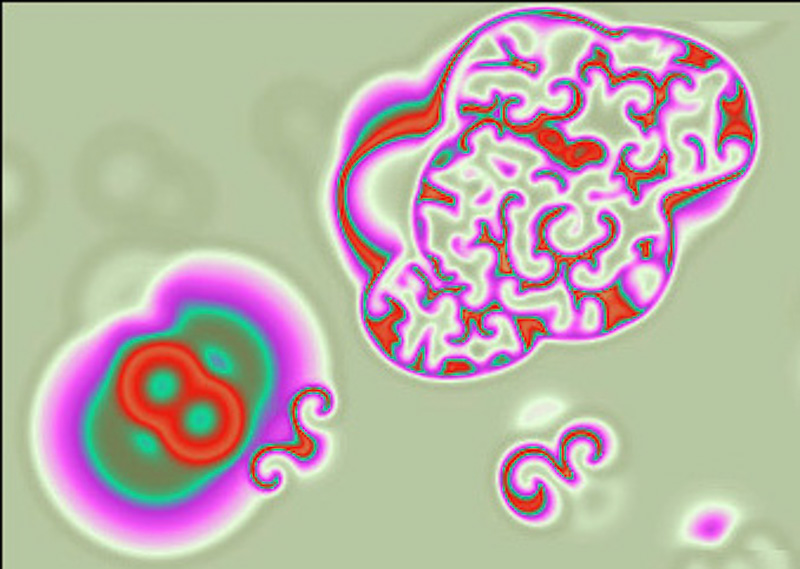

I’ve also gotten a lot from Silicon Valley. Cellular automata, or CAs for short, aren’t as well-known as fractals, but they’re equally beautiful. They’re like self-generating videos. You can get a CA running on your computer screen and it’s like watching a living oriental rug, or an out-of-control lava lamp with little bugs swimming inside. Over the years I spent hundreds or maybe thousands of hours staring at CAs. They ate my brain. A pure software high.

Landing in Silicon Valley in 1986 was a real stroke of luck. I kept on writing, but I got into being a professor of computer science for my day job. And I did some work as a software engineer at a big company. I was riding the wave—surfing those pixels for twenty years, out there in it every day, rain or shine. It was good. But now I’m glad I’ve retired from programming and from teaching CS.

When I see an old movie, like from the 40s or 50s or 60s, the people look so calm. They don’t have smart phones, they’re not looking at computer screens, they’re taking their time. They’ll sit in a chair and just stare off into space. I think someday we’ll find our way back to that garden of Eden. The machines will melt away.

First we’ll turn our devices into little plants and animals—that’s biotech. And then we’ll get to what I’m calling hylotech. This means that we’ll find a way to talk to objects and see that they’re quantum-computationally alive. And then it’ll be as mellow as the 50s again.

***

When I was younger I was more attracted to immortality than I am now. I think I was worried there were various things I might not live to do—travel, fatherhood, publishing. But now I’m more accepting of death. Nothing lasts. The petals whirl, the leaves fall, the river flows. Why fight it? You get the one lifetime and it’s enough. At some point you have to let go.

I think people who obsess about becoming immortal are loses on an ego trip. They don’t want to accept that the world will go on just the same without them. Certainly, as technology advances, we’ll see people living longer. And, at the more SF end of things, you might look for injectable nanobots to repair your body, or the use of fresh tank-grown clone bodies, or the ability to upload your mind into an artificial android body. I wrote about the last of these in my novel Software, thirty years ago. But in reality I don’t see any of these things happening very soon.

***

The “singularity” means different things to different people. In a way, we’re already well past a singularity, which was the coming of the computers. But in the early 2000s, people had a feeling that a much bigger change is coming very soon. There’s a hope that if you can just hang on for, say, another thirty years, then the nanobot or clone-body or digital-upload version of immortality will be available. Note that many of those spreading this promise are also offering to sell you expensive vitamins to help you hang on. They’re selling snake oil. It’s a con.

The reason I called my early 2000s novel Postsingular was because I wanted to leapfrog past the current wave of bullshit—and get out into the raw, energizing zone of all-new cutting-edge SF. There’s still a lot of wonderful stuff to explore. We haven’t come close to exhausting the riches of this world.

Interviewed by Nas Hedron, for The Turing Centenary, Brazil, September, 2012

I’ve always been bored by the idea of rigid, clunky, machine-like robots. I wanted robots to be funky and wiggly and sexy. I think it’s likely that if we ever have really useful and intelligent robots, they’re going to be more like tentacled octopi than like brittle ants. Of course thirty years ago, when I started writing about flickercladding and piezoplastic “moldie” robots in my Ware novels, this wasn’t at all a familiar idea.

Having gotten used to the idea of soft machines, it became natural for me to turn things around—and to have the cellular structure of human flesh become as malleable as the material of a computer display.

In my Ware novels there’s a drug called “merge” that lets people melt together inside a tub called a love puddle. In my novel Turing & Burroughs, a person who’s a skugger can turn into something like giant slug. There’s a scene where Turing and another skugger have sex by twisting themselves around each other while hanging from a rafter at Burroughs’s parents’ house. Mrs. Burroughs throws them out.

Reading a draft of this passage, my wife said, “Oh, you’re always doing this, having people merge together, it’s so icky.” And I’m like, “Yeah, but that’s sex, isn’t it? That’s how it is.”

We’re biological organisms—we’re not computers, and we’re not machines.

Interviewed by Aaron Marcus for UX, December, 2012, Berkely

For a number of years I’ve been writing about an interface device that I call an “uvvy,” which is pronounced to rhyme with “lovey-dovey.” It’s made of piezoplastic, that is a soft computational plastic. Thomas Pynchon had a substance like this in his novel, Gravity’s Rainbow—he called it imipolex, and I use this word in, for instance, my novel Freeware, which is a part of the Ware Tetralogy, now available in a free Creative Commons edition.

An uvvy sits on the back of your neck and interfaces with your brain via electromagnetic waves interacting with the spinal cord—most users will want to stay away from interface probes that stick into them like wires. The uvvy functions like a smart phone, but it’s activated by subvocal speech and mental commands. It sends sounds and images into your brain.

It’s absurd to see people pecking at their tiny smartphone keyboards. This is so clearly a bad user interface. It’s unnatural, error-prone, isolating, and non-ergonomic.

Interviewed by Monica Byrne for Damien Walter’s blog, December, 2014, Durham, North Carolina

In the’70s, when I was trying to publish my very first novel, Spacetime Donuts, I got a provoking comment from the SF master Frederik Pohl: “This is a fascinating read, but it’s not science fiction.” Naturally my feeling was that SF had to change. Indeed, much of the SF of that time seemed flat and uncool to me.

I was coming from a place where my favorite writers were Kerouac, Pynchon, Borges, and William Burroughs. I wanted to do the Beat thing of having my novels reflect my life; I wanted to have fabulous yet logical twists in my stories; and I wanted to use rich language. I believed in SF the same way I believed in rock’n’roll. Selling to the mainstream literary market wasn’t something I even wanted to try.

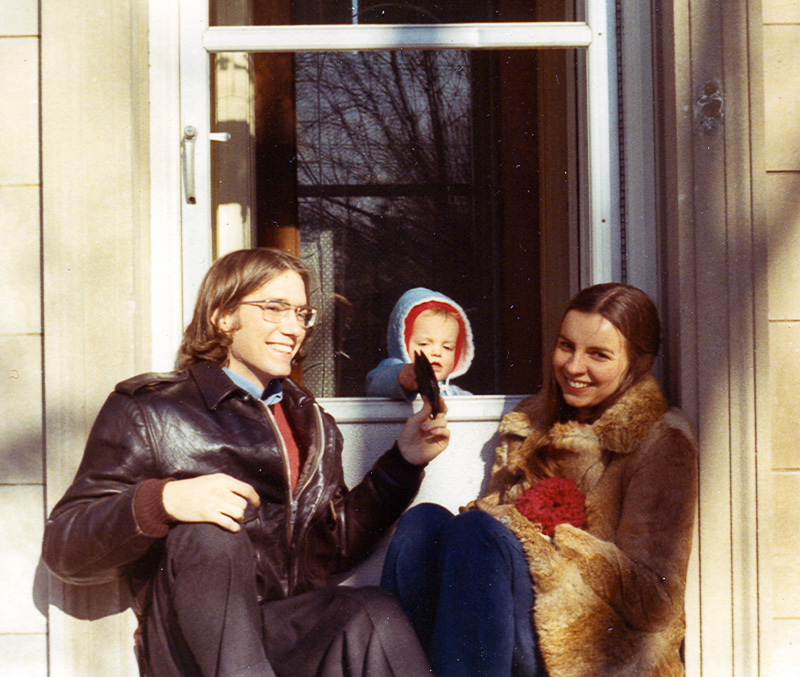

Eventually I was able to get Spacetime Donuts serialized in an SF zine. And then, early in the ‘80s, with White Light and Software, I was able to start publishing my SF novels in paperback. And then cyberpunk hit, and I had a few good years. My cyberpunk novels had a transreal core. Like in Software, the old man Cobb Anderson is modeled on my father. And the mad Sta-Hi Mooney, he’s a guy I used to hang around with. Of course, to some extent, both of these characters are me. As Phil Dick wrote in the afterword to his transreal A Scanner Darkly, “I myself, I am not a character in this novel: I am the novel.”

When I was younger, it made me uneasy to realize that I see the world differently than most people. Or at least I see things differently than most people admit to. And my oddball impressions of reality are something that I happen to be eager to talk about. Even though, at times, it feels like society’s forces are working to silence me.

But I was never the only outsider. I always have few bitter, rebellious friends whom I can relax with. Generally these are fellow mathematicians or hackers or SF writers.

At another level, I’ve come to realize that pretty much everyone alive has strange, idiosyncratic views. People pay lip service to the mind-controlling propaganda imposed upon them by the media—but deep down they don’t believe much of it. And that’s why there’s an audience for those who dare to step forward and speak.

Unconventional and transgressive ideas—they resonate with people. Momentarily surprised and awakened—an audience will laugh. It’s a laugh of recognition. My books tend to seem funny. But I’m not exactly a humorist. I’m trying to tell the truth.

***

Would I have thought of transrealism without drugs? Oh, sure. It’s not useful to try and reduce an artist’s ideas to drugs. Like, was Hieronymus Bosch high? Would it matter? You don’t really see other people painting like Bosch, no matter what they ingest.

This said, in the old days I did like smoking pot after hours, and I took psychedelics three or four times. Part of the appeal of getting high may be that it makes reality feel like SF. We tend to maintain an ongoing subconscious narrative about the world—naming and classifying the things we hear and see. When you disrupt that, you’re in a position to see the world raw, rather than seeing it as you’ve been taught.

And, as you mention, it’s possible to get into this mode of perception without being high. My writer friend Gregory Gibson terms this “the ongoing Venusian space-probe sensation.” It’s the sense that you’re seeing the world as if you’re a space probe sent by “Venusian” aliens, and you’re observing humans and their customs from the outside.

Interviewed by G. Brown for the fanzine nerds of a feather, flock together, May 2015, Los Angeles

Another angle for changing SF from within is to start writing about a set of ideas that haven’t really been touched upon yet. That’s a true and hardcore kind of SF endeavor. It’s not easy. You have to get yourself to look at the present day world with new eyes—as if you’re a Martian. You pretty much want to forget about all the SF plots and futurist-type prognostications. In the same sense that your characters shouldn’t mirror characters in existing works, your ideas shouldn’t mirror futurist ideas that you might read in magazines.

A good rule of thumb here is that if most people believe something—then it’s wrong. Consider: a hundred years ago, the human race pretty much didn’t know jack shit about science or modern technology. A hundred years from now, just about every single bit of tech that we’re using today is going to be gone. What’s going to replace it? Anything you want. Make up the weirdest shit you can think of. Be optimistic. Why not a new force of nature? Why not aliens from the subdimensions? Why not telepathy with every single object that you see?

Pile on the bullshit and keep a straight face. As the immortal David Lee Roth said, “It’s not who wins or loses—it’s how good you look.” If you and your friends can make your books fun and quirky, then maybe the soggy, stodgy SF ship of state will change its course.

Or maybe at this point it’s impossible to change the commercial genre known as SF. In 2015, there’s an alternate path. What if you sidestep the SF publishing niche, and shoot for mainstream publishing from the start?

It could be that the whole SF publishing industry is on its way out—or down. There will still be some great science-fiction books, yes, but they’ll be called something else. Transreal, visionary, speculative—like that. And the hidebound old trad SF label might really be fated to descend into subliterature. Maybe in ten years nobody will even consider publishing a good SF novel under the old SF rubric. Maybe the old category has been eaten by parasitic Martian blimps with electric news-crawl letters on their sides, or by institutional politics left and right, or, more simply, by cultural dynamics and the processes of media change.

It’s a bit sad. For me, it’s like I grew up in a nice small town—cue the silo-fulla-corn nostalgia routine—and I go back thirty years later and it’s all strip malls, and the city core is stone cold dead. As the Pretenders put it in My City Was Gone: “Ay, oh, where did you go, Ohio?”

The big loss for us mad-scientist, freakazoid, pinpoint-pupil SF nut-cases is that the mainstream market is harder to break into than SF publishing. Here in the nest it’s kinda okay for us to write funny. Me, back at the very start I was so daunted by the whole Brahmin Mandarin New Yorker vibe that I never tried selling into that market at all. I liked the idea of being an SF writer. I liked the image of being a rock and roll musician instead of an orchestra violinist.

But…if the orchestras are trying playing rock and roll, however ineptly, why not try for a gig with them? If you keep your soul, you’ll still be writing SF. Maybe better than before. Educating the squares. Showing them where it’s at.

Many paths, many futures.

Write on.

Interviewed by Liz Argall for Lightspeed, February, 2016, Seattle

Transrealism means writing fantasy or SF that is in some way based on your actual life. You’re steering clear of received media ideas and trying to write about your daily reality in a warped way. SF tropes become objective correlatives for your psychic drives. At times, I’ve based transreal novels on specific swatches of my personal history—such as college, say, or my experiences working at a software company. But these days I’m more likely to write what I call cubist transrealism. That is, I don’t go for a full reality-encrypted roman a clef. Instead I shatter my daily experiences into surreal frags and tessellate them into a tale. The juxtapositions generate the story and plot.

***

I think it might be easier to write a sad ending than a happy one. Sad or meh endings are a cultural default. People think a downer ending is tough, and hard, and realistic, and it’s bravely facing facts. So when you write a happy ending, you have to do it with the right touch, or people might think you’re corny or weak. But if you nail a happy ending, people like it. I almost always give my novels happy endings. People already know that life’s a bummer. So why rub that in their faces? We’re talking about escape literature, friends. Fairy tales. Entertainments.

Interviewed by Jeff Somers for B&N SciFi & Fantasy Blog, April, 2019, Hoboken

I’m blessed with a knack for drawing on both sides of my brain—the techy science side, and the dreamy literary side. I always wanted to be a writer. I was a huge fan of the SF master Robert Sheckley, and of the Beat author William Burroughs. And Jorge Luis Borges and Thomas Pynchon. And Flannery O’Connor. I studied math in college and grad school. Math always appealed to me. So clear and so intricate—the hidden machinery of the world. It is, as you say, a delicate balance to have a book be lively, with romance and fun characters—and also to have it be based on logical science ideas. In studying math, I learned about starting out with some set of assumptions like, say, Euclid’s postulates or the axioms of transfinite set theory, starting out with a set of rules and then deducing what follows from them. In my SF novels, I’ll make some wild, far-out initial assumptions. But from then it’s logical, and I get to see what ends up happening. I don’t really know in advance, not before I write the novel. That way it’s surprising and fun. I’m not trying to teach things to my readers. I want them to be amazed and to laugh and to be carried away.

***

An odd recent phenomenon is that lots of mainstream authors are writing SF. But they won’t admit it’s SF. Lifelong literary-SF writers like me find this … irritating. It’s like the upper crust authors can dip down into our world—but they don’t want to let us out. Even if we’re writing high lit. I always think of Kurt Vonnegut’s line, “I have been a soreheaded occupant of a file drawer labeled ‘science fiction’ … and I would like out, particularly since so many serious critics regularly mistake the drawer for a urinal.”

***

Let’s talk about the thought-experiment aspect of science fiction. When you turn your speculations into an SF story or novel, you go deep. You live in that imaginary world with your characters for weeks or months or even years. You unearth unforeseen glitches, and you move to higher levels of strange. Before I write a novel, I need an idea for something odd that I want to see happening.

One thing on my mind lately has been telepathy—I call it teep. I think it’s technically close enough that I could write about a teep biz startup. And I see a way to make it new. Another beckoning theme is politics. It’s stressful to write about that stuff. But these days, there’s a feeling that authors should speak up. So I plan to edit a special political SF issue of Flurb later this summer.

Looking further ahead, I want to write about a heretofore unnoticed force of nature. It’s at the subquantum level. It relates to dark energy, and to consciousness. And once we get it tune with it, we’ll have all the free energy we need, and we’ll be able to live inside electrons, like in my novel Jim and the Flims, and to predict the future from soap films, like in Mathematicians in Love, and to levitate, like in Million Mile Road Trip, and to talk to rocks, like in Hylozoic. But I know there’s something more than even that, something wilder and deeper, something super new that will, in retrospect, seem obvious and natural. We’ll be, like, why didn’t we think of that before! I hope the muse shows me.

Interviewed by Robert Penner for Big Echo, July 2019, Indiana, Pennsylvania,

Mathematics is a rich storehouse of shapes and processes and forms. You don’t necessarily have to be a trained mathematician to appreciate these riches. But you do have to read some popular math books.

The biggest new technique for exploring math is computer simulation. Realtime self-generating graphics. I’m an avid devotee of continuous-valued cellular automata. They’re like gnarlier, funkier versions of Conway’s classic Game of Life. I put these into my early cyberpunk novel Software—as constantly moving patterns within the piezoplastic skins of my robots.

Chaos, fractals, and Stephen Wolfram’s work have changed the way I see the world, and the way I think about it. I wrote about this in my non-fiction tome The Lifebox, the Seashell, and the Soul.

It’s kind of hard to explain the ideas in just a few words. A key insight is that that any interesting natural process—like an ocean wave, or a leaf twitching in a breeze—a process like this is fundamentally unpredictable. It’s too complex and gnarly for there ever to be a quick, short-cut way to know in advance what it’ll do next. But, and here’s the kicker, these processes are not random. Unpredictable, but not random.

That’s also the nature of your mind. You don’t know what you’ll do next. But that doesn’t mean you’re mentally flipping a coin. You’re like a chaotic, incompressible computation. Things emerge. You’re dancing with nature’s gnarl.

A mathematical idea or a story is elegant if it looks simple and clear, but a lot of deep thought that was needed to create it.

It’s hard to do this because you can’t think faster than you can think. Especially if you’re doing something like writing a story or designing a math gem. You’re running at the maximum possible flop. Your only hopes of a happy outcome lie in experience, patience and grace. And if it comes together—it’s elegant. A gift from the Muse.

Interviewed by Cody Goodfellow for Forbidden Futures, November, 2020, Portland

When I was younger, there was a certain default space-opera future that SF was supposed to be about. And cyberpunk was about breaking out of that. Fuck the Space Navy! Misfits doing crazy shit, that’s where it’s at.

I’ve done pretty well. Better than I expected as a raw youth. I used to nurse that less-than-famous writer’s dream of future veneration—a dream that’s like believing in Heaven, or Santa Claus. I’ve let that dream go. Even if it happened, what good would it do me when I’m dead?

I’m just glad I can still write at all, here and now—and be read. And if I get a real publisher with a real advance that’s great. And if not, I’ve learned how to do a Kickstarter to get some money for the book, and how to self-pub paperback and ebook editions. I don’t know if everyone realizes that you can actually do that for free. It took me awhile to figure it out. I call my imprint Transreal Books. So either way, I get my books out there. I won’t shut up.

For me, stuff like space-travel feels used up. Unless you were to do the space travel in a car instead of in a spaceship—like I did in my recent Million Mile Road Trip. But there’s so much that’s untouched. Biotech has endless possibilities, and there’s ubiquitous physical computation, and the hylozoic notion that everything is alive. See my pair of novels Postsingular and Hylozoic for more about that.

And I keep wanting to write about that totally new thing that we know someone is going to discover in the next hundred years, and I keep not quite getting there, but by dint of making the effort to think that hard, I’m finding new stuff. Not actual “true scientific theories,” but fun ideas like new kinds of wind-up toys. The store is big.

For decades I read Scientific American to keep an eye on what’s new. But sadly they’ve turned to shit—small fonts and articles about—gak—sociology and political policy and economics? As if. Nowadays it’s enough to keep a loose eye on Twitter, and see the wonders trundling past—like a holiday parade that never ends. Grab hold of anything you see—and tweak it a little bit, and make it your own. Connect it in some way to your actual personal life—that’s the move I call transrealism. And go a little meta—that’s a trickier tactic I’m always trying to master—flip your idea up a level, and into something having to do with states of consciousness, or with the nature of language, or with the meaning of dreams. Go further out. There’s still so much. We’re just getting started.