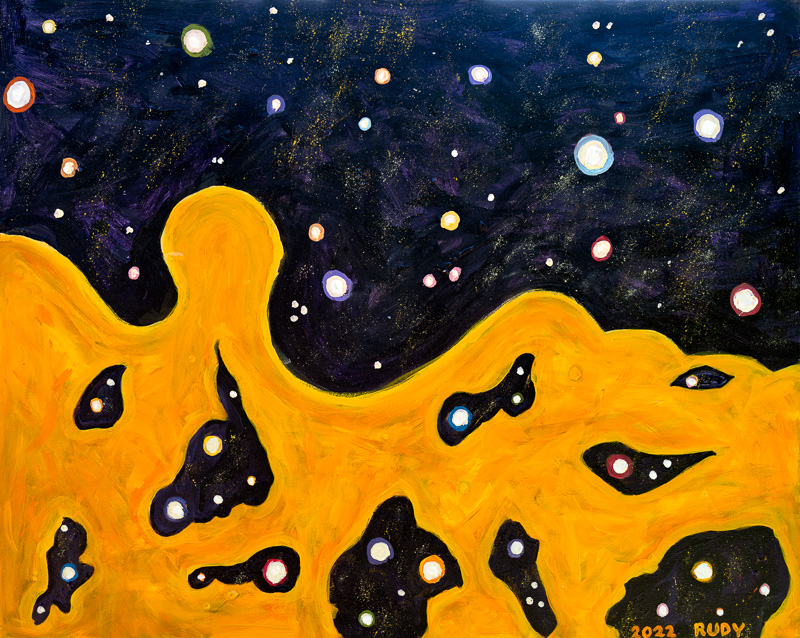

I’m done with space paitnings for now. I sold my now-finished New Glasses to my nephew Hans von Sichart. It’s a very nice painting; I put in a whole extra day on it, sharpening it up.

Hans came to our house to pick it up; it was nice to see him, had been nearly ten years, even though he lives in the bay area. He was saying I should do a version of the painting where the books are inside the lenses and the topographic stuff is outside, but I don’t think that would work.

I enjoy talking to him, a fellow German. We’re not exactly the most sympathized-with minority around, so it’s nice to huddle together. Thinking back to the Irish kids who hassled me in my Catholic high school, St. X.

I can’t get into writing anything these days, other than these notes. Might as well keep painting, although just now I’m waiting for a fresh delivery of canvases. I do have one very small one; might use that. I’ve painted twenty since January of this year. Really need to sell some more of them. I’m running a sale with insanely low prices.

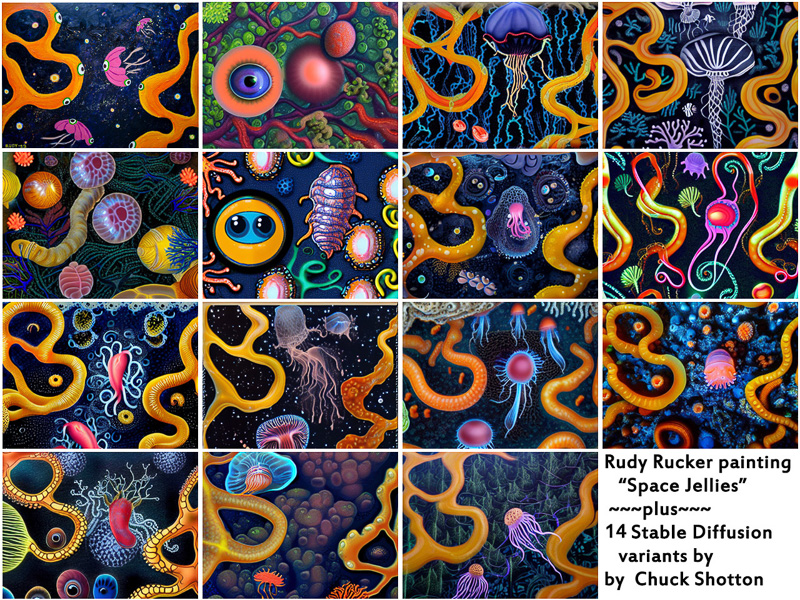

I just sold “Space Jellies” to Michael Koch in Europe. Maybe I’ll just have a new career as a painter. Why not? I still can’t quite get over the hurdle of finding, or trying to find, a gallery to sell them. But the mail-order thing does seem to work pretty well. Monetizing my fan base and my social-media-following. Hi, guys.

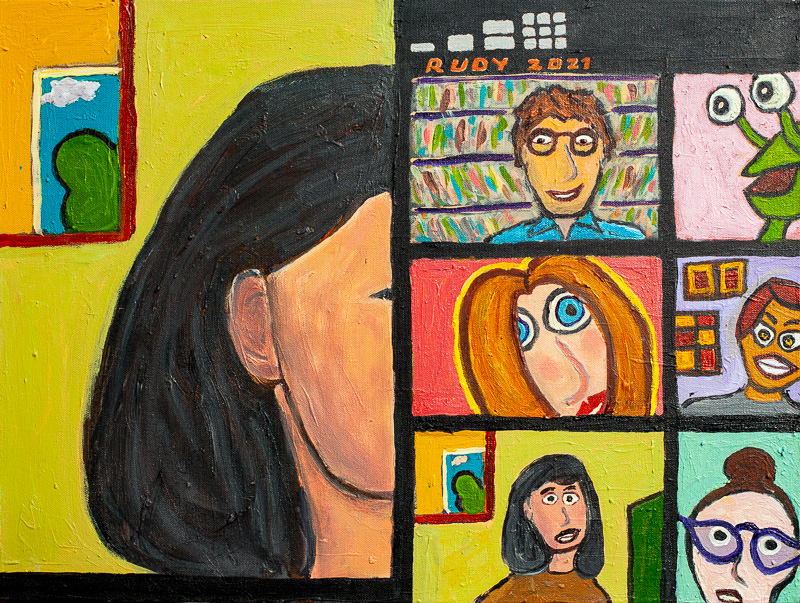

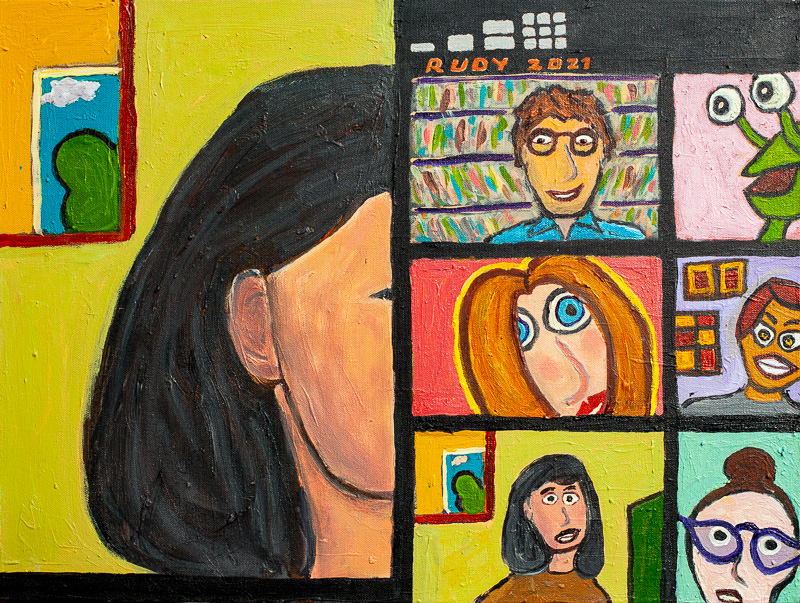

My old Lynchburg pal Mike Gambone popped up, and he’s buying Zoom Meeting, a great piece.

Isabel came down from her town of Fort Bragg, CA, near Mendocino to visit for five nights, and that’s great. As I write this at breakfast, I hear Isabel talking to Sylvia downstairs. The music of their voices. Wonderful.

I really miss writing. I guess an idea will come. I feel sort of tentative these days, not knowing what’s in the offing. I’m still waiting for the canvases I ordered to arrive.

Every day I see my Genoa painting Rush Hour, from November, 2019, 40” x 30”. It’s hanging in the upstairs bathroom. I don’t know if I can ever do a painting that good again.

I found I had two very small, high-quality blank canvases I’d been saving in the basement for maybe the granddaughters to use. But think now I’ll use at least one of them a miniature saucer painting. Just to be out in the yard/studio. Doing saucers is a no-brainer, and they always sell, even if, for me, they’re a bit been done. Maybe or once I should do a sketch—to get good positioning for the saucers. (But I know I won’t.)

Frozen saucers in this old one, Deep Space Saucers from 2015, like a flash photo of a tossed handful of M&Ms. Adjusting the colors is a big thing in these. Like Gerhard Richter’s “paint-chip” works. I sold this one to a computer guy called Bob Hearn, and now we’re friends.

And here I am with the new one, called Saucer Pals. Why am I so pink? Well, that’s the balance it takes to make the canvas look right. Or maybe I really am pink. More sensitive to the sun than I used to be.

For this one, I eyeballed and revised and tweaked to find my way to this new composition. Didn’t bother to do a sketch, didn’t use shading. Took me four sessions. Small paintings aren’t necessarily less work than big ones. What made this one fresh was that I had the idea of giving them eyes, like I recently did on thsoe cosmic jellyfish, and that really livens up the picture.

Meanwhile a buttload of canvases showed up from Blick. Maybe I paint some stacked-layer saucers a bit like Jim Woodring’s jivas, which I’ve painted before?

Meanwhile a woman named Janell Julian in greater LA wrote to buy my diptych pair of two 30 x 24 inch paintings Cute Meet which I’d marked way down. I shipped them off and she got them and she’s “So very happy.” Makes me glad.

Daughter Georgia arrived with granddaughter Althea for four days.

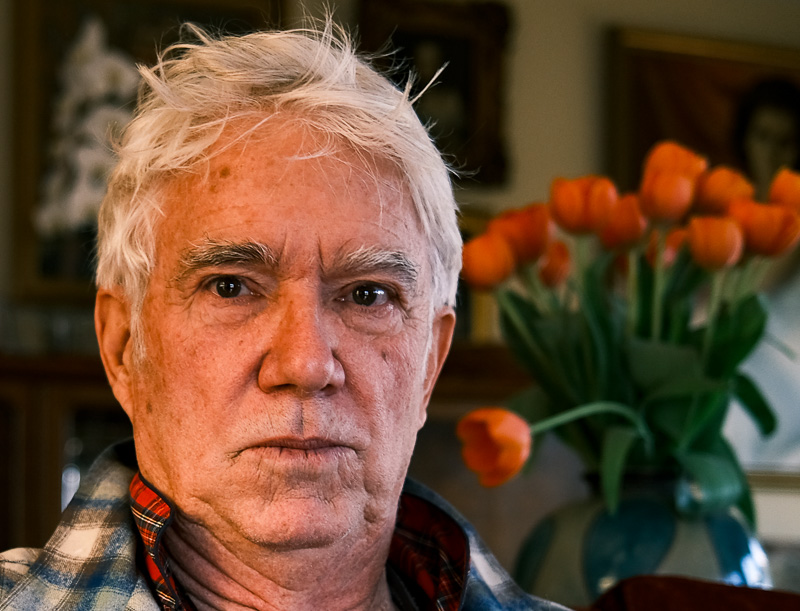

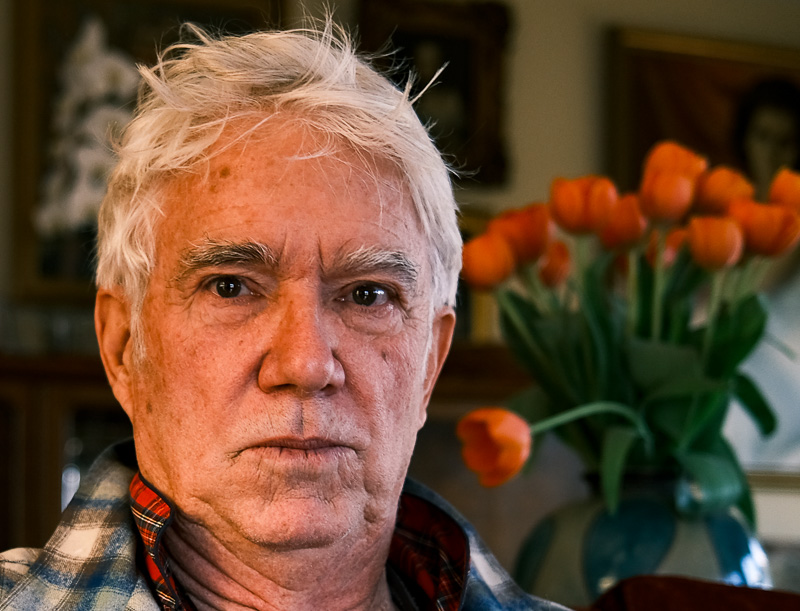

Usuallly I look really nice when the kids take my picture, but this time, for a joke, with Althea taking my picture I looked stern. Althea shot this with her new camera; a Fujifilm x100V of mine that I gave her, the camera barely used, because I had immediately replaced it with my Leica Q2.

I started a new painting with Georgia brushing on it too. The canvas was super bump because I’d covered it with random daubs of the leftover paint from the one before. Fun to work together with Georgia; we understand and agree with each other so easily.

Then I kept working on it. It has a pair of glowing-blob-creatures with those cartoon eyes I like to draw these days. The eyes looking at each other. As usual the two beings “are” Sylvia and me. Ab-ex woods around them, with tree trunks that Georgia painted in. Possibility of lake and sky in the background. The trunks were straight redwoods when Georgia was here, but after she left, I warped them into twisty oaks. Working title was In the Woods.

We went walking around Los Gatos High with Georgia and Althea, the school where all three of our kids graduated. A genuine fall tree here.

And Georgia left and Sylvia and I had a great trip up to Mendocino/Fort Bragg for Thanksgiving with Isabel and her husband Gus. plus Rudy Jr and his family.

Rudy Jr kindly picked up and drove Sylvia and me the whole way there and back. Stayed at the glorious yet folksy Beachcomber motel on the cliffs just north of Fort Bragg. And Isabel’s loft full of art and comfort.

That’s granddaughter Zimry in the hammock.

I got some good photos at dusk on the last day, especially one of grandson Calder on a rock with the moon. Sometimes I want to advise Calder about this or that, and then I remember that my own grandfather, also named Rudolf von Bitter, didn’t seem to approve of me. And I don’t want to be “that” grandfather, although it amuses me that I might be. The wheel of time.

In point of fact Calder isn’t so different from what I was like when I was ten. I was…difficult. I open my heart to Calder and love him. My grandson.

Isabel and Sylvia with Isabel and her husband’s badge quilt…they collect patches from the places they visit, and sew them on.

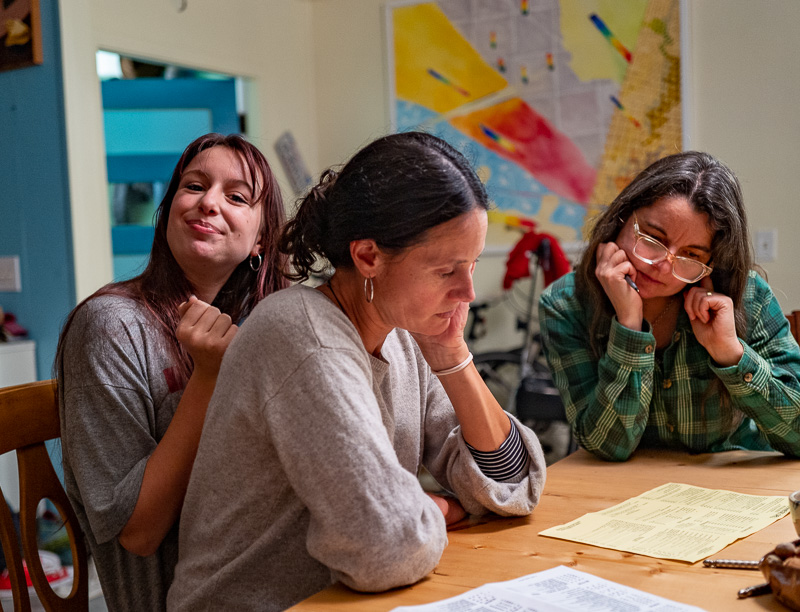

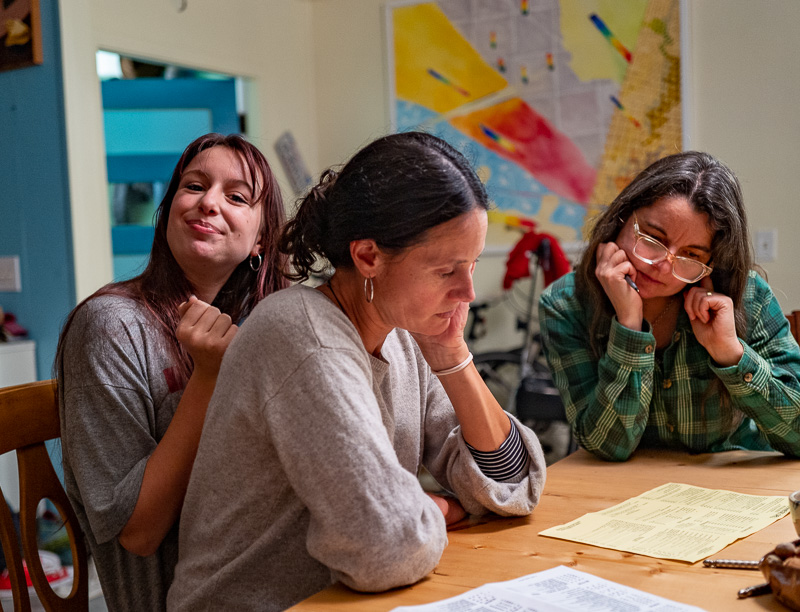

Jasper, Penny, and Isabel at the table, reading stuff. A casual shot.

Low water seen from a cliff. Nice curves.

There’s a huge stand of Monterey pines at the Beachcomber motel. right outisde our window. Lit by the rising sun behind us, with the Pacific out beyond. Uplifting. What is there to worry about, really.

LIttle Calder perky in Isabel’s indoor hammock.

Isabel and I were griping about the dumb experssion “sneaker wave.” One of those phrases that annyoingly catch on and become received wisdom: some waves are rogues and they sneak up on you. When really it’s just a matter of never turning your back on the chatic ocean. Which is what I was doing, just before taking this photo, and a wave surged to the middle of my shins, soaking my shoes for the next two days. Sneaker wave!!

What a photo. The setting sun gilding the hummocks of wet sand. That’s what I call Leica quality. No decaying into pixels, no distortion, a pure fiffty-megabyte raw image with all the info there to caress with Adobe Lightroom and Photoshop till it’s got just right gleam.

Jasper loves to jump. . Didn’t think of using a high shutter speed, but the blur shows the motion, and it’s all good. The roughness of the surf.

On the drive home from Fort Bragg we stopped in Petaluma, and saw some memorably ugly fake xmas trees. Cheerful, though. And I like the Santa with shades.

This is a mere Pixel 7 Pro phone image, but what the hey. The best camera is the one that you have with you, right?

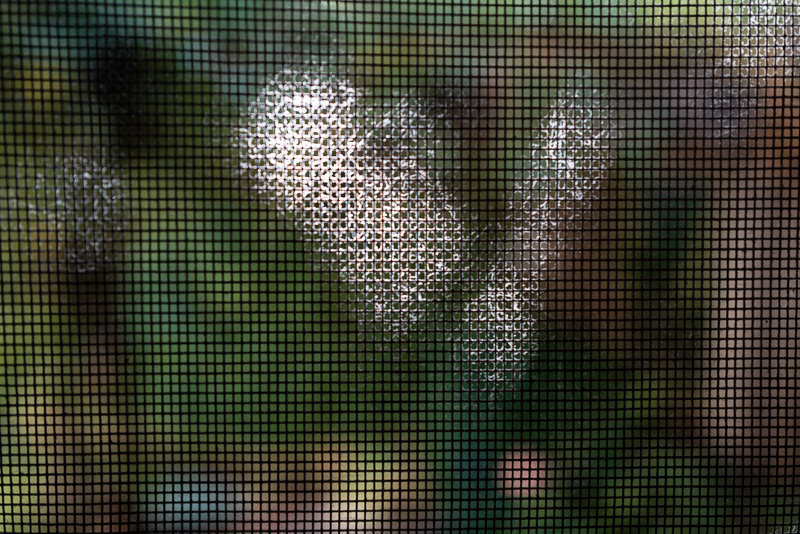

Awed by the twittering birds in the trees on St. Joseph’s Hill when I walked there at dusk with Sylvia the other day. It had been raining. Lot of trees, with the tweeting birds…maybe just paint the tweets themselves and not the birds.

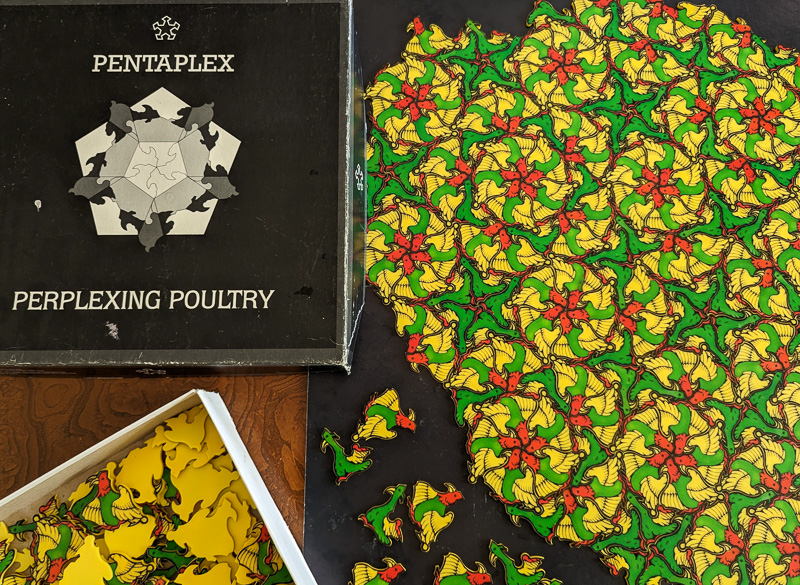

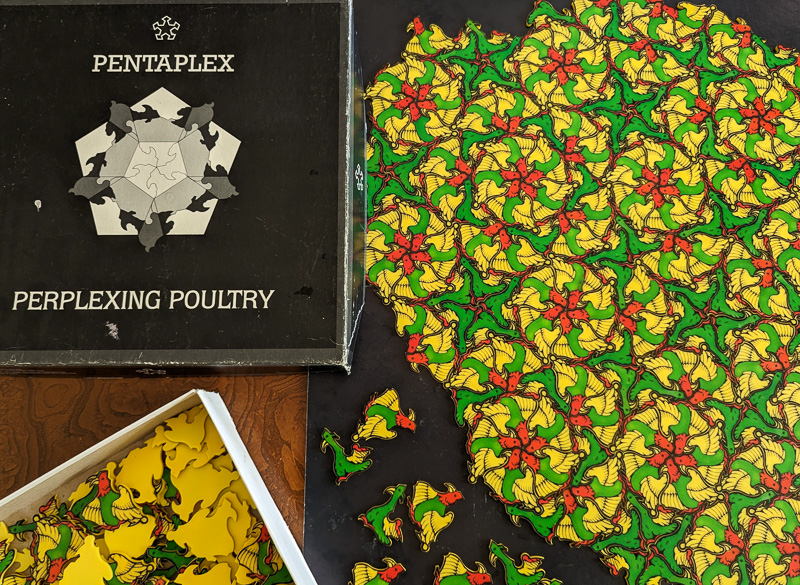

The tweets are triangles. In saying this, I’m thinking of mathematician Roger Penrose’s “kites and darts,” that is the non-repeating tiles he also sold as “Perplexing Poultry.” Perplexing Poultry in the trees. I wrote about them in Freeware.

The low sun shining bright through an uphill scrim of branches. “That’s the White Light, Sylvia,” I say. “That’s where we’re going.” And she’s, like, “You go first.”

Double 32 on a dumpster. If that’s an exponent, its about the size of a quindecillion.

Still no real thoughts of writing, although, yes, I dis see a seed for a time-travel story. There’s a spot in the St. Luke’s church parking lot that I always use, the first one on the left, it’s usually empty. And if I travel back here from the future, or forward to here from the past…that’s a likely spot I could stake out, with good odds of finding myself there in at least a day or two.

What would be my motive? What outcome would result? Infiltrating Silicon Valley from the node where I emerged on a hilltop above San Ho.

Meanwhile Nature actually bought my short-short sorry “Who Do You Love” for their online “Futures” site! I have to reread the story, by now I don’t quite remember it, even though I did six paintings for it. Not a novel, no, but, hey, it’ll be in Nature!

I worked some more on that painting that I started with Georgia, the one I’d been calling In the Woods. During the seventh or eighth revision, it hit me that the shape in the middle — which was already an island by now — could be an island shaped like a UFO, so I changed the work’s name to Saucer Island. For the closing touch, I did an off-white frieze across the middle, which really makes it. The leaves on the top have a nice fauve Gaugin/Cezanne feel.

Erich Schaefer in San Francisco bought the painting the same day I posted it online.

It took me a couple of days to mail out Saucer Island, and our friends Ronna Schulkin and Jon Pearce came over for a visit while we still had it. I had the usual discussion with Ronna, who’s a very accomplished painter. In my paranoia, I sometimes think she’s suggesting that my paintings aren’t “real” paintings because they’re “narrative.”

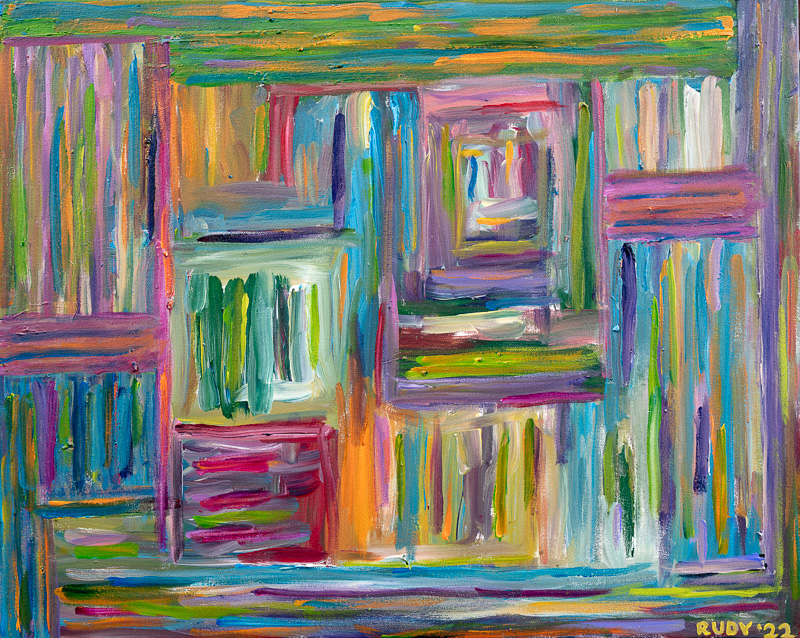

Certainly she is a better painter than I am. I’ll freely grant you that. Check out her website. Or just look at the Ronna painting shown above…we bought if from her about ten years ago. Worth every penny. I think about it every day. Ronna is cagy about what this is a painting of. Maybe it’s her and her two siblings. But mostly it’s about pattern and color.

Does the more clearly narrative element of some of my works entirely vitiate them? Well, id=often my narration is quite oblique. It’s not like Hallmark cards or editorial cartoons. As I always say, I like to think of my paintings as illustrating forgotten adages or unknown fables. Like Bruegel’s The Peasant and the Birdnester. You don’t quite know what’s going on.

In any case I greatly enjoy my discussions with Ronna. It’s rare I get to talk shop with a fellow artist. And I’ve known Ronna and Jon for so long. Thirty-six years by now.

And then, while wondering what to paint next. I was leaning towards something more surreal or abstract and less “narrative.” My dreams are odd these days. More vivid, more repetitive. Could I do a painting of my uneasy dreams?

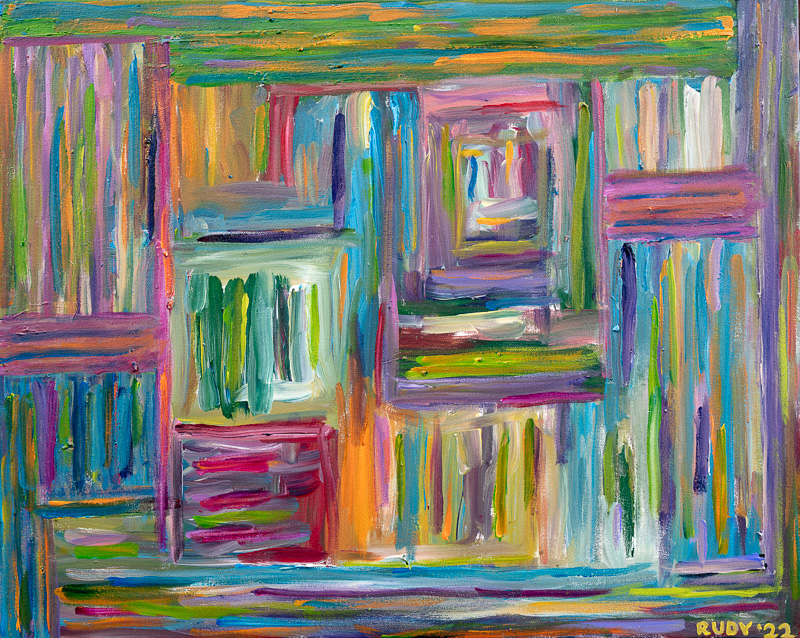

Here’s the painting I ended up with, and I decided to call it Underground because there’s something like green grass at the top—it’s not that I deliberately “put grass” there; it’s just that, on the third revision, I felt like putting green, because of the color harmonies, and a hour later it occurred to me that it could be grass, and if it’s grass, then, whoa, kind of creepy, there’s all that stuff underground. The stuff of uneasy dreams.

Is this a narrative? Maybe, maybe not. In the end, every painting is a narrative, isn’t it? Even if you don’t know that you’re narrating. You’re drawing your own Rorschach blots.

I do know that I did three sessions, and every time the painting changed a lot. It’s always hard to know if you’re making a painting better or worse. In a way I liked the very first rough version the best, and that one only took me about twenty minutes. But I didn’t want to be done yet.

Painting is kind of an up and down thing, like the stock market, and it makes sense to bail out when it looks like things are in good shape—even if they’re got as great as in your sentimental recollection of the first day’s flash, and not yet as wonderful as your vain fantasies of future glory.

In the background as I write this in the coffee shop, Elvis is singing “In the Ghetto.” Life is a trip.

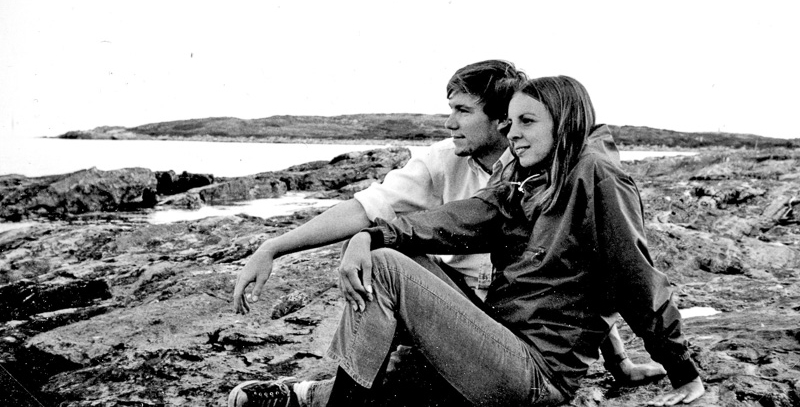

Back upstream a ways, here’s Sylvia with my parents’ dog Friedl in 1966. Sylvia and I were in our early twenties, engaged to be married.

And here, in Geneseo, New York, 1976, are Isabel and Rudy Jr, wearing colanders like WW1 soldiers. Love how Isabel’s onesie is a little tight on her tummy. And Rudy swigging from his silver juice cup.

And good old Mom, in her prime, probably about 55. The years, ah, the years.

And now another year is winding down. Love to all of you.