(Revised this post on Aug 30, 2012) I gave a talk and reading in Gloucester, Mass, on Wednesday night, 7:30 pm, Aug 29, 2012, at the Gloucester Writers Center.

I made a podcast of the event. You can click on the icon below to access the podcast via Rudy Rucker Podcasts.

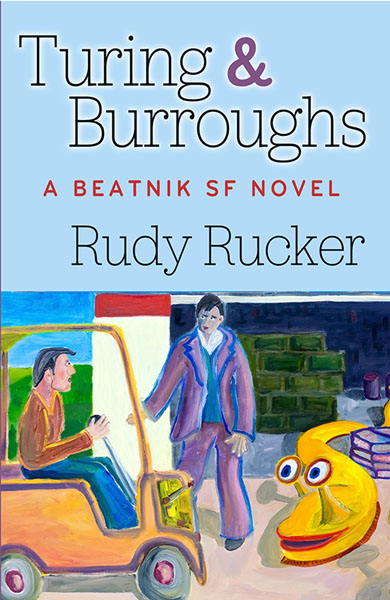

My topics were transreal SF and beatnik writing, particularly that of William Burroughs. I gave a short reading from TURING & BURROUGHS, folowed by Q&A touching on Burroughs’s cut-up technique and contrasts between fantasy vs. SF. The introduction is by my old friend and fellow writer Gregory Gibson.

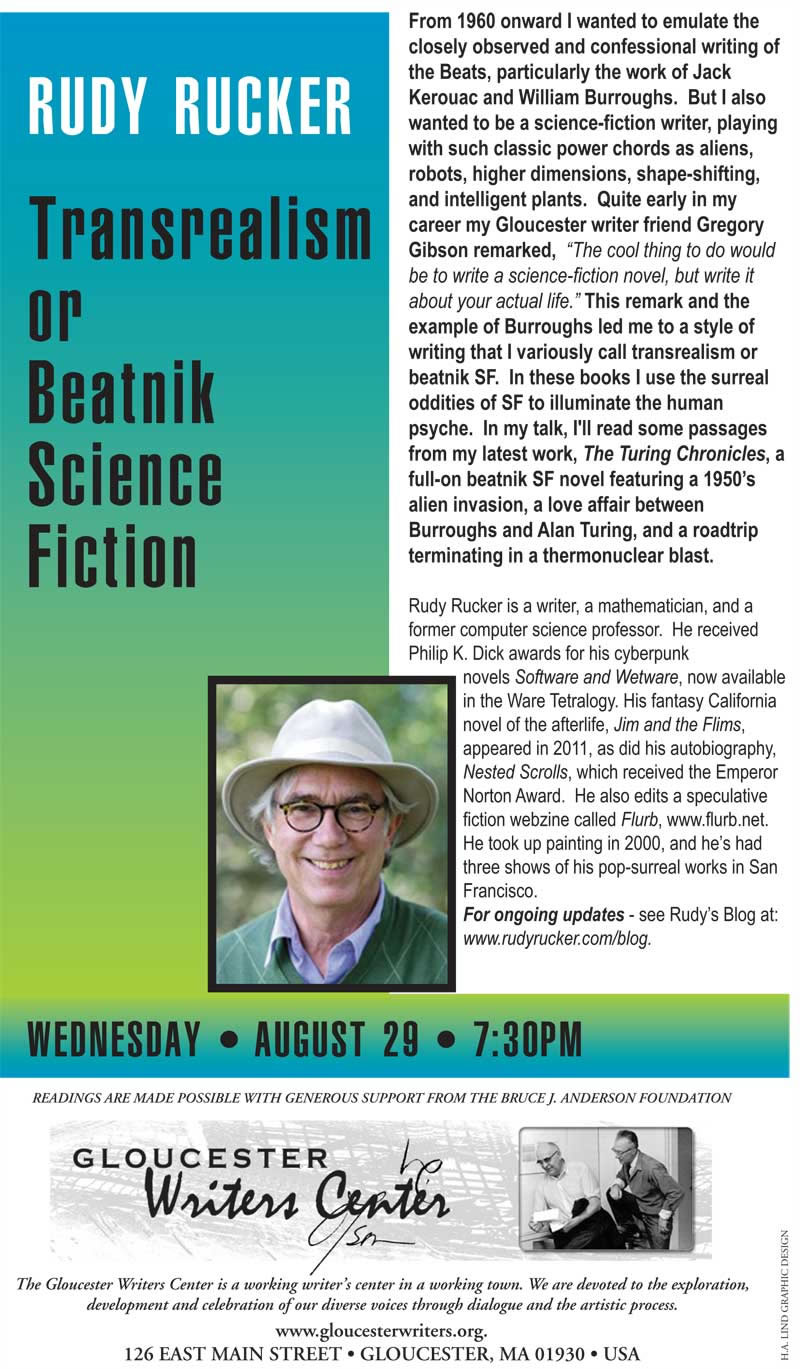

You can see the web announcement of the talk here. And see the poster below (note that my novel’s title has changed from THE TURING CHRONICLES to TURING & BURROUGHS.)

I’m here thanks to my old writer friend Gregory Gibson, and thanks to Henry Ferrini. As well as spreading the word on Beatnik SF, I’m pre-promoting my upcoming TURING & BURROUGHS novel.

Be there if you can. And if you weren’t, see the podcast link at the stat of this post.