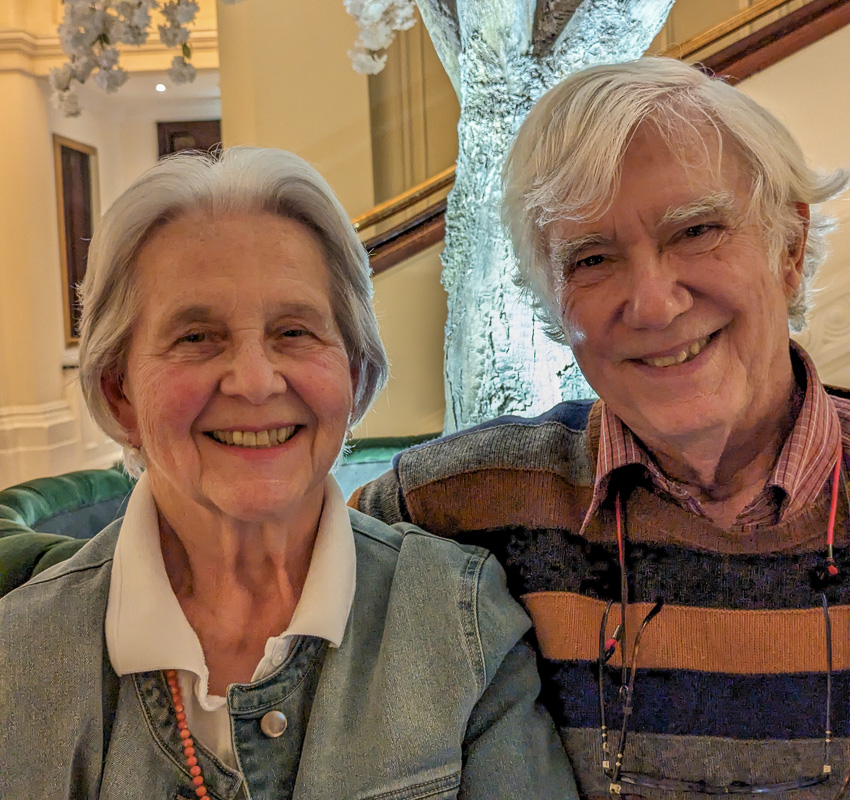

Early in 2024 I started spending time with Barb Ash, who I met in the Los Gatos Coffee Roasting. Being with Barb makes me a lot happier than I’ve been for the last year and a half. I’m glad I met her.

In May, we went ahead and did a trip to England together, spending ten days at a BnB in London, and a couple of days near Stonehenge, and in Bath. As it happens Barb is a photographer, and some of the time we went around with our cameras, advising each other on shots. I still have my Leica Q2, and she uses a Nikon 7, selling her photos through stock photography sites, and having occasional shows around San Jose.

And of course I often resort to my Pixel 7 phone. “The best camera is the one you have with you.” And all the photos of me are by Barb.

By a humongous monument in front of Buckingham Palace. Can’t remember who it’s in honor of. Probably not Keith Richards

This is a really excellent guitarist we spotted in a tube station. I told him he played like Jimi Hendrix. He said, “Jim Morrison too. All the Jimmies.”

This is what I call a “Rudy picture.” My eye is always picking out abstract patterns. This is an especially rich one. In the downstairs of the V&A, or Victoria and Albert Museum of…everything a Victorian might ever be interested in, one of each.

The cafe at the V&A is outrageous. Amazing baroque ornamentation. Makes you regret that modern times happened.

With my niece Siofra Rucker at a high-end fish and chips place she took us to. Not far from our B&B in the Marylebone neighborhood. Siofra works for an American school in London, and is currently working on an MBA at Oxford, no less.

Barb and me!

Wandering around London is an endless treat. This is near St. Paul’s Cathedral. Love that green.

I think we saw this view from the Tower of London grounds. Some amazing postmodern architecture in London…like two steps beyond. So why NOT have a building shaped like a cartoon toaster. We’ve got the modern materials, and software that can generate utterly strange blueprints.

Cool tiling of the floor of the New West End Synagogue in London.

The New West End Synagogue. Love the Hebrew writing. Barb was particularly interested in photographing the place. We went on a weekday, when no service was taking place, and it was exceedingly hard to get in. Locked up tight, for obvious reasons. But they had a buzzer with a speaker, and I told the guy that were two Jewish American photographers, shooting images for shows and our websites, which is more or less true, except the part about me being Jewish, although I do have a Jewish ancestor or two, a few steps up the family tree.

Inspiring, sacred, other-worldly place.

Staircase at the old Tate art museum, the stairs go up to a coffee shop. Dizzying spiral.

Peter Bruegel, “Adoration of the Kings,” 1564, at the National Gallery, off Trafalgar Square. I saw this painting some years before I wrote my novel As Above So Below, an imagined account of Brugel’s life. My only historical novel. It was this painting which inspired me to write my novel. As noted in my Journals, I saw it with Sylvia on September 12, 1998. Here’s what I wrote.

How clear and fresh the canvas is. The three kings are in a triangle of gaze, each looking at a gift held by one of the other kings. Balthazar looks like Jimi Hendrix at the Monterey Pop festival. He has a beautiful pointed-toe red boot. Fringed chamois leather cape. His gift is a gold ship called a “nef.” It holds a green enameled shell, and within the shell is a tiny live monkey.

The gallery note by the picture says that Bruegel put soldiers in his pictures because for most of his life the Netherlands were occupied by Spanish soldiers. This touch makes it seem so real. Makes me want to write Bruegel’s life. The rainy Flemish day, right here in front of me. I want to go there.

Mary is a hot cutie with full lips. A guy whispers in Joseph’s ear. He’s saying “You’re a cuckold. Mary had a lover.” Joseph looks undisturbed.

In the background are a bunch of interesting characters. A guy with glasses, maybe a money-lender. Also a classic Bruegel fool. And a fat guy like you’d see at the farmers’ market.

Great to re-visit the painting after twenty-six years. And good to show this talisman to Barb.

Here I am with my first cousin Gabriela von Bitter, known as Ela or Mauni in the family. Barb and I had lunch with here in the Charing Cross hotel across from the National Gallery. I’ve only seen her once since I was a boy. Her main memory of me is wat a terrible, spoiled, American child I was, this would have been when I was perhaps eight. Apparently the whole family still remembers that visit. The key story is that my aunt and uncle has us over to their well-worn manor on their estate (a farm). And they offered me some summer sausage salami. But I only wanted to eat the peppercorns in it. So I ate the peppercorns, and put the meat under my couch cushion. Barb listened attentively.

When we went outside again, it was raining even harder. We took a break in a church with a very cool window over the altar. Like a warp in Hilbert space instead of the usual Holy Family with Grandpa God.

A nice photo of Barb when we had high tea at The Parlour in the Great Scotland Yard Hotel off Trafalgar Square. It was pouring rain, and I was stumbling around in watery gutters, staring at my phone map, and thank god I found this spot. Incomparable. Joyous.

Here’s St Margaret’s church at Westminster Abby. near the Houses of Parliament. I like the knobbly look. Like an appetizer tray. We had trouble getting inside at first.

Sun-touched Big Ben with House of Parliament (?) mighty chariot chariot and a tube sign.

We had fun walking along the Thames looking over at the London Eye Ferris wheel. It turns very slowly, like the minute hand on a clock, you get a one-hour ride. But we didn’t get around to it.

Interesting shops in the Marylebone neighborhood where we stayed. These folks were selling…scents.

We got together with yet another of my relatives in London: my cousin Mauni’s son Edward Marr. He’s always been a reader of my SF novels, and I’ve corresponded with him over the years. Recently he was working for companies who distribute magazines. Was fun to hang out with him and hear that wonderful British=style speech.

Definitely a Rudy picture. Love the blobby slug that’s made of twigs and leaves.

We spent most of a day at Portobello Market, full of booths and shops. Liked these veggies in a van.

The sign on this Ukai cafe really appealed to us. We spent some time sitting there…twice, after walking the market up and down.

Some fellow Ukai patrons. To me they seemed like hip Londoners, but who knows.

A Rudy picture of the loos.

Terrific graffiti, and the bloke striding by, and the electric scooter. Perfect.

Cool “stepped” painting in a Portobello underpass. Looks totally different from the two ends.

We finally got into Westminster Abbeyby taking a walking tour. This lady was our tour guide. She had a lot of personality and a British accent and lots of informative asides. I loved her.

Here out guide is pointing out the tomb of ISAAC NEWTON. We calculus teachers like to think of him as mathematician first, and a physicist second. Our hero. Great to see one of our own getting the full treatment here.

.

Architectural bric-a-brac. But I’d rather see this than a blank wall!

Outside Westminster Abbey, a plinth and a tree embrace. Adam and Eve.

And now were off to see Stonehenge. It’s near the town of Salisbury, which has some quaint old zones. This was the view from our window.

A gate into the “keep” or park around the Salisbury cathedral. Love this ancient stuff.

Rudy picture.

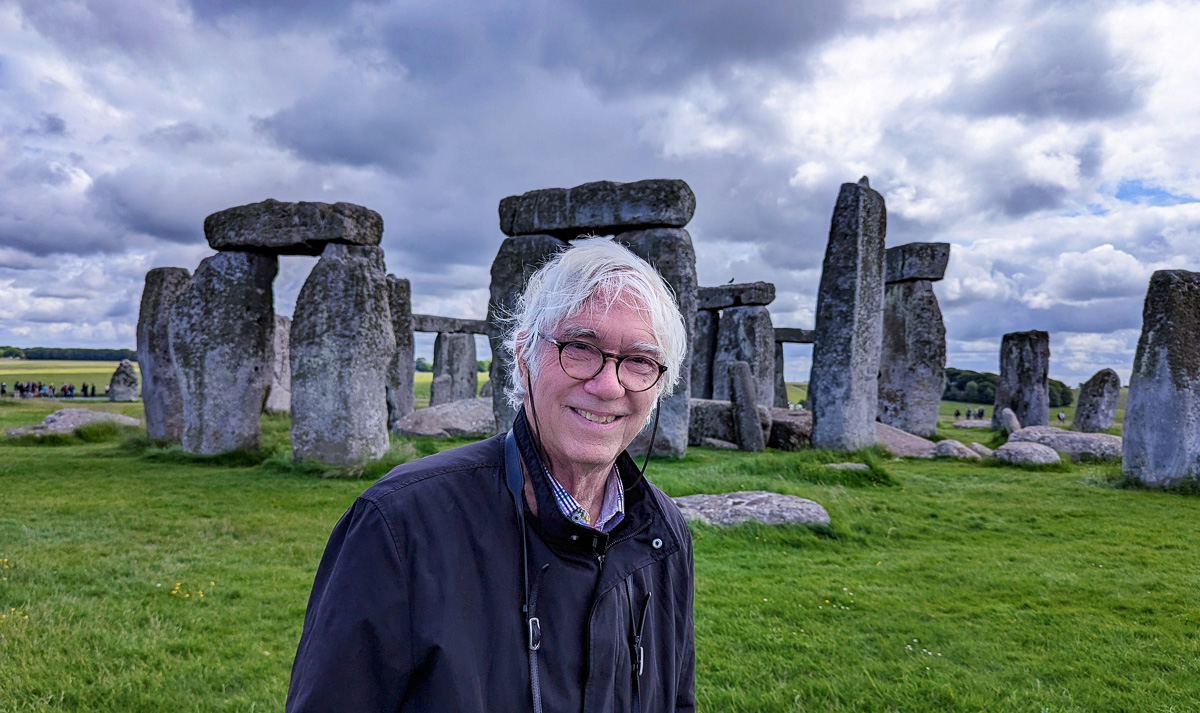

Getting to Stonehenge was kind of hard. You get a taxi from Salisbury, and it drive ten miles to the Stonehenge center which is itself a mile or two from the rocks, and wait in line half an hour for a bus, which takes you to the site, which becomes very crowded over the day. A low rope barrier blocks you from going in and touching the stones which is, on the whole thing, a good thing, as otherwise this photo would have about fifty or a hundred people crawling around. You’re not allowed to touch them. So–in a way it’s a letdown, and the stones are smaller than you might expect—but even so, it’s awesome. Maybe four thousand years old.

Barb on the scene. She herself was up for darting in to touch the stone. “It’s not like the guards have guns.” How we Americans think…

You can’t take just one photo. Love the clouds.

Picnic supply shop. Vape supplies?!?

I seem to be a Druid.

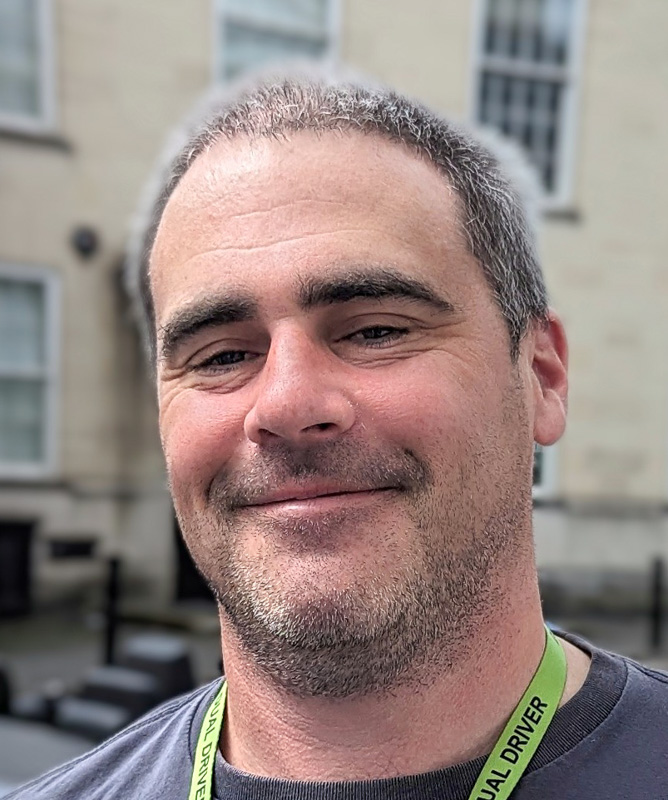

This man drove us back into Salisbury in his taxi. It was raining once again, and it was sort of hard to call a cab. For some reason, as soon as I got in the cab, they guy exclaims, “You’re an author!” And it wasn’t like he’d ever hears of me or seen a photo of me, it was just a random shot. Maybe it was my long white hair. And then he tells me this kind of great story how he’d written a novel, and the authorities had seen it, and they’d called him into the back room and and had forbidden him to ever write a book again. “I can relate,” I tell him. “I get rejection letters like that all the time.” What was wrong with his novel? Well, he’d described how his mates in the army actually talked, and the manuscript accidentally fell into the hands of the police, who’d been searching his house for some other reason, and they passed it up the chain of authority, and that was that. In the US a book like this might conceivably do well.

The floor of a little gallery off the Salisbury Cathedral where we saw an actual copy of the Magna Carta. Seems there are several copies. It’s pretty long and I couldn’t quite get the drift.

Another photo of that same quaint window view.

I think the English call this a barrow.

Our last stop was at a pricey inn named, of all things, The Pig, near Bath. Siofra suggested it to me. Siofra knows of course that I am of course fond of pigs, and that I fact think of them as my totem animal. Barb was dubious, but the place was great.

Bath is a lovely town with tons of ancient-looking Roman architecture, although I understand that a lot of it was rebuilt after WWII. Plenty of cute shops, like this stained glass place.

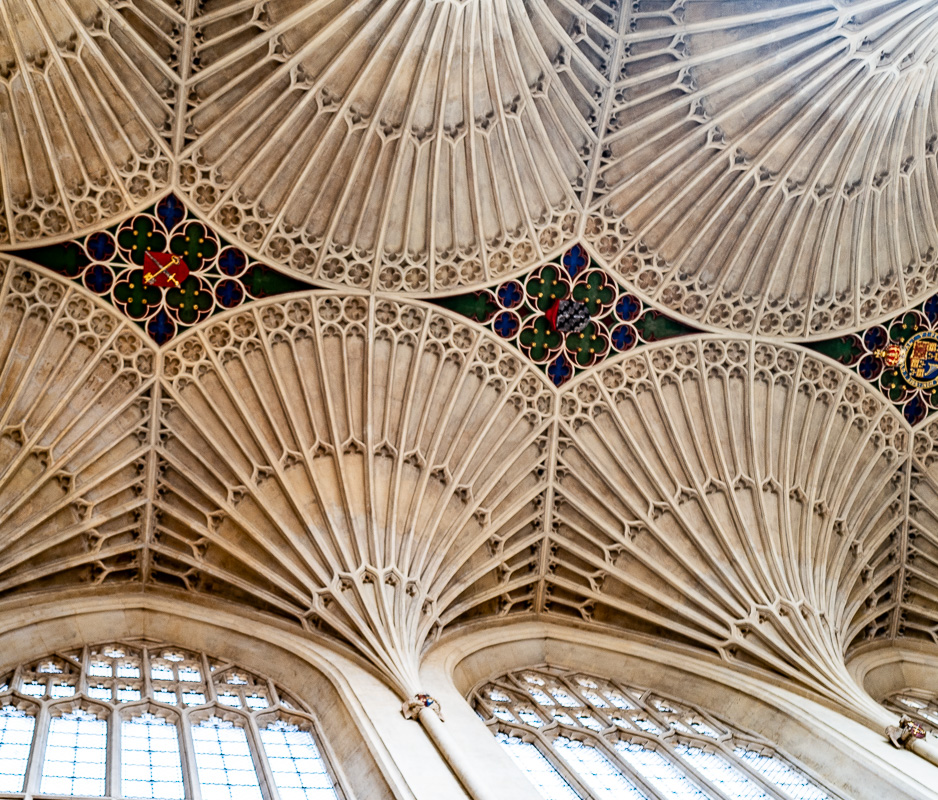

Excellent “ceiling” a High Gothic church there.

And Barb in an arcade. We’d just been dancing in a square to the tunes of some street musicians. Vacation

This kid was incredible. A juggler on a roller board holding forth on what he was doing, with elements of comedy thrown in.

Pope Rudy.

Last sight we saw was a little pay-as-you-enter riverside park in bath, featuring, among other things, a large carved-wood slug.

That’s all, folks.

And, oh, here’s a painting I made the other day. It has nothing whatsoever to do with our trip.