So now I’m getting back to our trip to Budapest and Vienna. This is the Vienna part.

The cathedral is all bumpy like drip castle at the beach. The story is that Sylvia’s great-grandfather designed the stripes in the tiling of the cathedral roof.

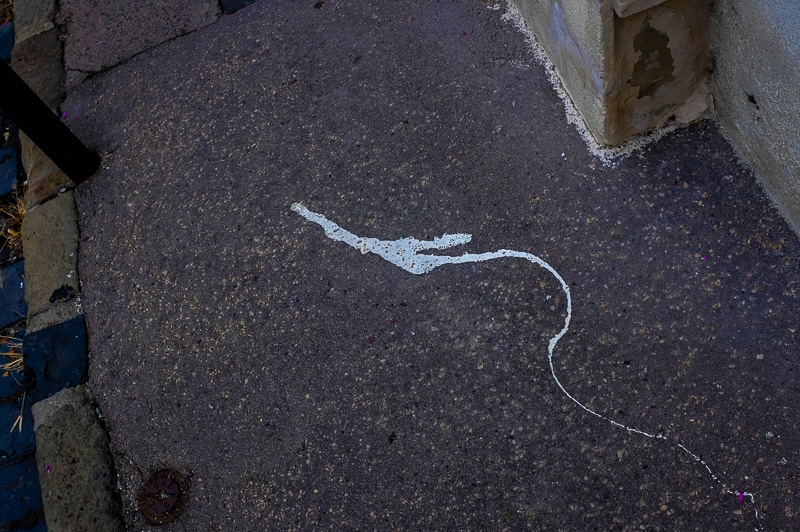

Vienna’s really deluxe and classic in most of the downtown. Imposing buildings at every turn. Dig this fountain with the naiad (or whatever) holding the eternally gushing clam.

Statues up along the balustrade of a giant building, maybe one of the castles. Like sharpshooter feds at the big DC marches we’d go on during the ‘Nam war. Love those clouds.

Plenty of buskers in Vienna, playing, like really high-level Mozart sonatas. Music hath charms to tame the wild Rancid fan.

We made two visits to the KHM or Kunsthistorisches Museum or Art Historical Museum. They have a big stash of paintings by Peter Bruegel the Elder, my main man. I wrote the story of his life as a novel some years ago, a novel, As Above, So Below. You can find my booklength “Notes” for the book on the book’s home page as well.

This painting here isn’t a Bruegel, it’s a Rubens, called “Head of Medusa.” Severed head, done by Perseus as I recall. Supposedly Rubens didn’t paint the snakes himself, he called in a subcontractor artist, a special snake man.

I love the wild old Victorian-type art halls where they squeeze in paintings by all the 2nd and 3rd raters. The jumble bargain bin rising to the—oh wow—heavily enhanced coffer ceiling.

Great savage crocodile with some water babies. How exotic and strange the African animals are, even now. I think maybe this one was by Rubens too.

Bushes outside the KHM, when I see these bushes, I’m excited, like I’m on the verge of artistic ecstasy. I visited this museum about seven times while working on As Above, So Below.

Daughter Georgia was with us for the first two days in Vienna and I got her to come see the Bruegels with us. She really appreciated the KHM—she was, after all, an art history major. It wasn’t even especially crowded in there. With “Peasant Wedding” in the background. Like a whole novel in a frame. Great to be there with Sylvia and Georgia.

The KHM collection includes one of my very favorite Bruegel paintings of all, the “Hunters in the Snow.” Here’s a detail. The tired hunters, looks like they only got one animal, maybe a fox. All the emotions and feelings in those dogs. The little puppy-like one on the right floundering through the snow to be as fast as the others, and dog on his left checking him out. The one on the upper left weary and damp. That curled Borzoi tail of the one dog at the lower left who’s sniffing the other dog. . The image is like a teleportation gate, if I look at it for awhile I can go into the painting. Which is in fact the technique that I used for writing my Bruegel novel. I went into 15 or so of his paintings and lived in each of them for awhile, and wrote a chapter for each painting about what I saw while I lived inside it.

We got tired every day pounding the pavement, the weariness grew greater every day. So nice to go back to the room and put up our legs.

Starting out the day, interesting to see regular Viennese doing their jobs. Carpentry.

Lavishly decorated biking sign.

Eternal construction projects on the big Hofburg palace. Like the Germans, the Austrians never tire of retrofitting their architectural treasures.

I love walking around with my camera and seeing pictures. In this one I like how the untrimmed shoots are sticking out of the evergreen tree, and I like the 3D space curve of the hose. And of course the massive stone walls and the heavy iron grate. And the shadow of the prickly evergreen on the right.

Wrought iron can be fairly aggro.

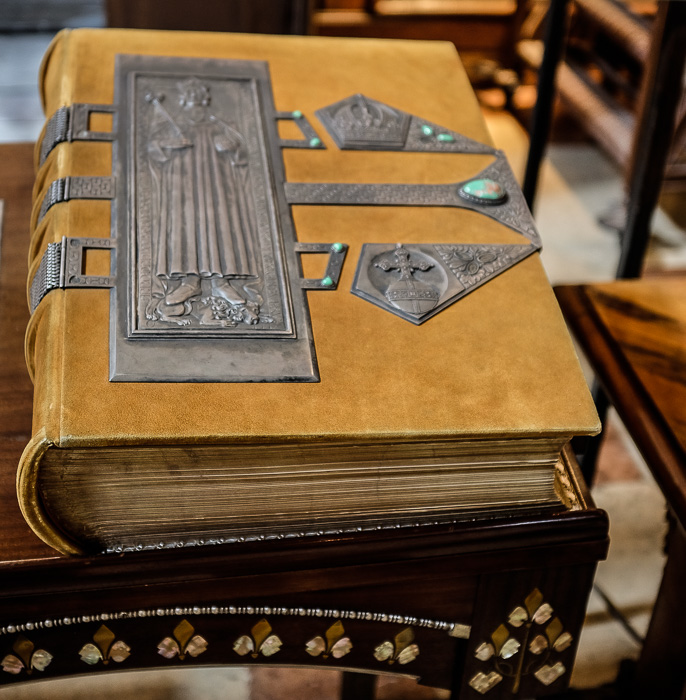

Sylvia’s brother Henry met up with us in Vienna, and we ended up on some old library inside the Hofburg palace, lots of leather-bound books that you can’t imagine any of the aristos ever read, and this one really Big Book.

So classic, this old library, with the big marble statues, and the baroque encrustations on the ceiling, like mussels all over a wharf piling. And all them books.

Talk about encrustations, how about this giant gold ball atop the Hofburg gate. Maybe that’s the sun and those ladies are rolling it along?

Even the chains are intense and heavy-duty and bronze in Vienna.

Just to get off the beaten track I dragged Sylvia and Henry to the museum of the Globes. Like map globes. This thing here is kind of an orrery, like you use to demonstrate the motions of the planets and the moons. But this one is especially designed for explaining the phases of the moon. I think the candle in the middle is the Sun, but there’s an extra mirror on the right to, like, focus the Sun’s light more intensely.

The Magnificent Seven Plus One. Great globes of history. Actually these ones don’t look super old. On some of the really old ones, they have, like, California completely wrong, as nobody had ever made it there from Europe.

I can’t believe how old I look anymore. Mad scientist holed up in the Globe Museum.

Luscious wrought iron, enhanced by its shadows. It’s better to skew some photos, you catch the perspective better. People used to ask the street photographer Garry Winogrand about his photos being off-kilter and he’d flatly say, “They aren’t tilted.”

Awesome Art Nouveau poster for the Secession building erected for counter-academic art around 1903. So Fillmore West, too. Isn’t it time for Art Nouveau to circle round again?

I’m such a Bruegel fanatic that I made sure we stayed in a hotel only a block away from the big KHM museum where the Master’s works reside. Good view of the place from our attic-level window. Casing the joint. The “Hunters in the Snow” shall be mine!

Cool Deco style china closet by the Wiener Werkstätte (Viennese Workplaces) of, I dunno, maybe the 1920s. The shadows make the shot.

Dig the 3/4 moon in the reflecting pool. Near a big church whose name I forget, across the big “Ring” road from the Mozart concert hall where they have the special concert on New Year’s Day every year and you can watch it on TV. The do shows every day for tourists too. If the show is for tourists, the musicians put on Mozart outfits. Obviously if you’re a local you don’t want to see the concerts where the musicians wear costumes. But they play just as well either way.

Some good action on this wall. I always love the deadly lightning-bolt warning signs. Plus the Picasso-like sketch on the fuse box. And the big flowing red tag with kind of a Sanskrit feel to it.

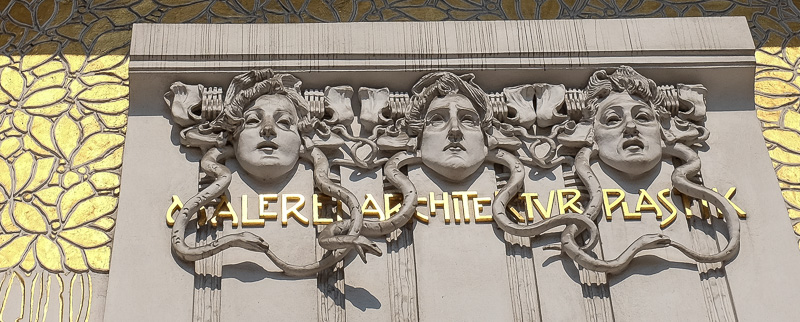

Over the door of the Secession building. Like I already said, it’s so Sixties, echoing from the Tens.

Drab subway hall with a nice curve to it.

And below, amid the Hephaestean clangor, the men are repairing the escalator. Seems like it would be hard to do.

Another dose of Baroque schmaltz. I like the rococo decorations right inside the window frame up at the top. And this church had a good-ceiling dome paintings. The gods glancing down at us, not all that concerned with what we’re up to. Like café society habitues noticing the rabble on the street.

Thanks to Tweeting about my progress, I connected with one of my readers, a lawyer in a great old office near the cathedral, Karl Arlamovsky, a good guy.

I like this shot, with the man exiting the corridor to the cathedral square. The Luxarado sign makes a good balance.

Women on the subway escalator. The hair of the woman on the right seems very fairy-tale.

Another great graffito. I like that ends in the question mark. And the window with the interesting stuff in it, like the half-head, and the reflection in the wiggly old windowpane glass.

This is me in a great Vienna cafe called the Central. I had this great pastry called “Mohr im Hemd,” warm chocolate cake with a “shirt” of whipped cream and ice cream.

One of my main goals in life had been to eat this treat again—I’d had it Vienna about fifteen years earlier. Can you believe the ceiling? For awhile in the 50s the place was a bank, what a waste. But then it went back to being a café. They say that both Franz Kafka and Sigmund Freud used to hang out here in the early 1900s.

So back to the KHM, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Art-Historical Museum. Behold a drinking horn, perched playfully like a puppy on his little legs. “Ready for a run, Master?”

Here I am with another of my favorite Peter Bruegel paintings, “The Conversion of the Apostle Saul.” Wonderful deep sky in this painting. As I mentioned I have a “Notes on Bruegel” document online as a PDF, I put it together while working my novel about Peter, and if you scroll down through the doc, you’ll find I have fairly detailed notes on each of the Mater’s 50 known paintings.

A detail from “The Battle of Carnival and Lent.” The beggars are great, so passionate. And the thin, mean pig or varken as you say in Dutch. And the little guy in the motley outfit of stripes and red. It just doesn’t get any better than Bruegel. And, since you ask, his name should not be pronounced “Broygel,” nor should it be spelled Breughel. He spelled it Bruegel, and his Belgian countrymen pronounce his name “Broogel,” with maybe a bit of a throat-clearing sound on the g, but never mind the throat-clearing, just say Broogel. Like bagel with roo inside. And I’m Roo.

This detail from “Peasant Dance” knocks me out. The guy on the right, he’s, like, drunk who’s worshipfully intently into what the musician is doing, like Jack Kerouac staring up at a sax player, or like a guy my age fixating on Keith Richards onstage. And the musician himself, whoah.

Quirky parting shot from the KHM museum…we noticed a little group going around, getting a docent-led tour, and the guide is…transgender, in full drag, rich with voice modulations and flamboyant gestures. The guide’s herd of tourists, they were, like, enthralled. And Bruegel was glad.

Our last night in Vienna, we got together with this cool countercultural agitator Konrad Becker, over the years he got me invited to Vienna twice for paying gigs, his politics are, like, complex literary criticism of our seeming reality…more info at his World-Information Institute page. He guided us to a hipster café on the old city wall. Right when we saw Konrad he was really into the new Pokemon Go game…he was walking all around Vienna playing it, and meeting lots of people at favored Pokemon swarming spots in parks.

Wonderful cities, Budapest and Vienna. I was sorry to leave.