Reader Jonathan Flynn points out that my Gigadial podcasts are visible on Feedburner, and that the Feedburner format is easier for his iPod to digest. Eventually (in 2015) I began posting my talks via Rudy Rucker Podcasts, see the button above.

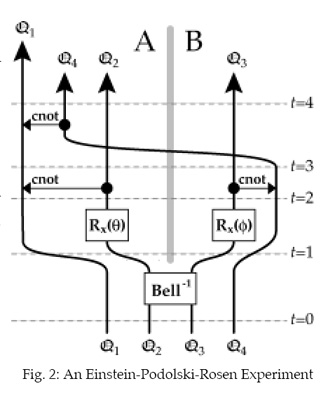

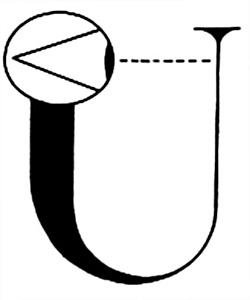

The great visionary physicist John Archibald Wheeler coined the phrase “It from Bit” to represent the notion that perhaps the universe emerges from digital computations. [The picture above is a famous illustration that Wheeler used not to symbolize “It From Bit,” but rather to depict the unrelated (?) notion that “the universe is a self-excited circuit,” meaning that because the universe (U) contains wave-function-collapsing observers (eyeballs), it is in some sense bringing itself into existence. I’ll bring this picture into the discussion a little later on.]

When I argue for universal automatism in The Lifebox, the Seashell, and the Soul, I say that every process is a computation. Does this mean I’m arguing for an “It From Bit” position?

Yes, but — three buts.

(But 1) Perhaps it’s more useful to focus on there being computations at all scales. I’m more interested in thinking of computations as existing at all sorts of scales, as opposed to focusing on some possible ultimate ur-computation “underneath it all.” The ripples on the water are a computation of a large-scale computation being performed by the water, and there’s no need to delve deeper. Simply sticking at this level tells us a lot already: (a) The ripple patterns are computationally universal, (b) Even in the absence of any changes to the input flows, the ripple patterns are unpredictable in the sense that there’s no exponentially-fast shortcut prediction method, and (c) Given any proposed theory of physics, there are infinitely many statements about the future behavior of the ripples which cannot be proved or disproved from the theory. (All this is discussed in Chapter 6 of The Lifebox.)

(But 2) Maybe there isn’t one single computation that does it all. If we do go to the lowest scale, it’s not clear that the Many computations have to fit together into One computation. That is, I can imagine a swamp of computations at the lowest level, with our universe emerging above the swamp like marsh lights. We know from mathematical set theory that there are indeed classes of things that can’t be thought of as single entities — the classic example is the class of all sets. It could be that the class of all computations does not allow itself to be thought of as a single computation — somewhat analogous to the fact that the class of all humans is not itself an individual human. This is a subtle philosophical point. The class of all computations may not be a computation.

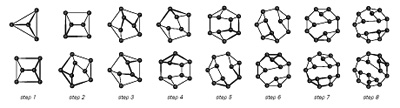

(But 3) Even if there is one universe-generating computation, we don’t need to imagine it as “running on something.” Suppose we can go to the lowest level and find one cosmic computation down there that generates the universe. Stephen Wolfram is optimistic about finding such a computation. He feels it should be what he calls a “network rewriting” system. From his studies of computation, Wolfram feels that in most interesting cases, a given computational task can in fact be performed by some very simply defined computational rule. So he's optimistic that if he does a brute force search over, say, the first trillion possible network-rewriting rules, he'd going to find a Fundamental Physics rule capable of generating our reality. That would be kind of amazing. Now suppose something like Wolfram's idea were to succeed. Suppose we do find some rather simple computational rule that, if run through enough cycles, can produce something resembling our universe. At this point, people often ask, “What is the system that this ur-computation is running on?” I’d think I'd like to say there isn’t any system that the ur-computation is running on. The ur-computation is running itself. It’s the bottom level. No elephants standing on turtles standing on turtles, dude. All that's down there is a network rewriting system. But why is it there? Ah, that's the unanswerable cosmic Superultimate Why question. That’s all she wrote, bro. And maybe now’s a good time to invoke Wheeler’s big U with the eyeball. The universe is dreaming itself.

I’m blogging about this topic today because I got a nice email from David Deutsch recommending his paper, “It From Qubit”. He’s interested in arguing that if there’s a cosmic computer it should be a quantum computer rather than a digital computer. To argue against the digital “It From Bit” position, he sets up a straw-man in the form of a “Great Simulator” which we universal automatists supposedly believe in. The straw-man Great Simulator belief corresponds to the Matrix-style notion that our reality is akin to a video game running on a desktop under some Geek Goddess’s desk.

Deutsch sets the Great Simulator straw man afire in these words, “A belief in the Great Simulator] entails giving up on explanation in science. It is in the very nature of computational universality that if we and our world were composed of software, we should have no means of understanding the real physics – the physics underlying the hardware of the Great Simulator itself. Of course, no one can prove that we are not software. Like all conspiracy theories, this one is untestable. But if we are to adopt the methodology of believing such theories, we may as well save ourselves the trouble of all that algebra and all those experiments, and go back to explaining the world in terns the sex lives of Greek gods.”

My defense here is that although I think there could be an ur-computation, I don't believe in a Great Simulator. And, backing up, I'm comfortable thinking of my universal automatism as simply saying the universe is made up of computations, without having to claim there is a superultimate aha computation. To be continued…