Chapter Four is well underway now, I have about 4,500 words on it and a pretty good outline. It’s the same routine all day, day after day. Write a page, print out what I have, mark it up, type in the revisions and maybe write another page, print it out. Now and then I have to take a break to figure out what’s next. I print out the outline and revise that. Or take a nap.

I’m going to hang out on this blog entry for a week or two, just re-revising it and hoping comments accumulate.

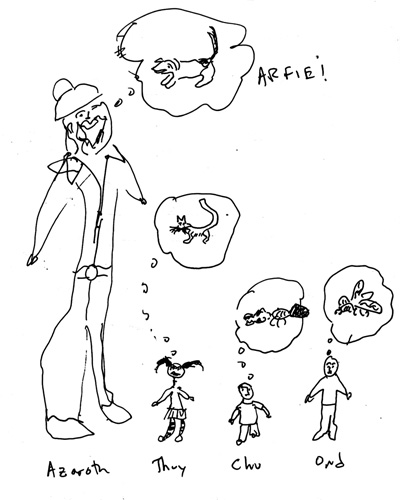

Right now Thuy, Ond and Chu are walking down Highbrane Valencia Street. They’re about one foot tall relative to the Highbraners, and they move six times as fast as the Highbraners. Like speedy gnomes.

It’s Christmas Eve (we have Jesus who died on the Cross, they have some unnamed figure who died on the Triangle and is symbolized by a cuttlefish, not a lamb), and people are out shopping. They’ve had telepathy forever in the Highbrane, also they can teleport themselves at will, also they have omnividence (can see anything), and they have endless eidetic memories. And the objects are telepathic too, although they don’t speak English. I’ll use “teep” for a verb to mean “using telepathy.”

Due to telepathy, people have a better control of morphogenesis, and can tweak organisms to take on desired forms. A shop where a guy grows you the kind of tropical fish or mushroom or orchid you want. Teasing a growing plant or animal into a sought-for shape is a delicate craft. I would call the people who do it shapers, but Bruce Sterling has made that word his own. So call them coaxers.

Question: what’s for sale in the stores?

What’s the street scene like?

The buildings are organically grown, or rather assembled from organically grown parts. The windows are like membranes. Parts from a Victorian tree farm. Branches that look like trim.

I’m thinking they have cars for cruising around and carrying stuff even though they have teleportation. But maybe the cars can be flimsier as it’s pretty hard to run into someone by accident, as you can teep them. The cars can in fact teep things themselves and avoid collisions. They are assembled from morphogenetically grown parts.

The buildings and cars aren’t organisms yet, not like in Frek and the Elixir. They’re assemblages of bio-like parts. The cars know what kinds of parts they need, the mechanics teep with them. Maybe the cars scavenge for spare parts sometimes, perhaps stealing from each other. Azaroth, Ond, Chu and Thuy have their secret meeting in a room over such a garage. The mechanics know they’re there, but don’t bother to squeal.

Clothes stores. Clothes are for warmth and decoration. Not really much point in modesty, as you can see under the clothes. But people are kind of used to that. Maybe sell hush-undies that scold teepers who nose under them, though not talking in words — as I suppose our objects don’t speak language — just reacting with anger and scolding and shame. Of course, for some, hush-undies could make the hidden contents seem forbidden and therefore extra-alluring! Blush-hush.

Food markets, restaurants. If we have telepathy we can really watch the chef. Maybe there’s someone with such a great sensitive palate that it’s pleasure to mind-meld with them as they chow down. Or the food talks to you, showing you its past. You’re eating with the chef’s whole sense of the process, the preparation, and as you eat it, the chef’s eye guides you, he’s put teep-tags onto the food.

Would people still get drunk and high? Sure. Imagine the havoc you could wreak getting wasted and “running your brain” instead of just email or phone or conversation. So there are bars that are “screened” so you’d be unlikely to teep out of there and get yourself in trouble.

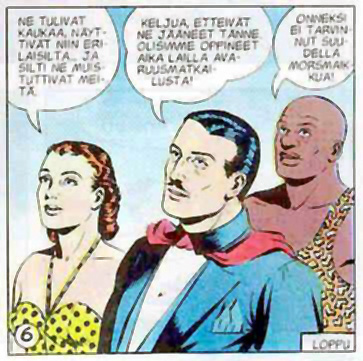

Screened by overriding musical stylings provided by a black guy with shaved head, sitting with muscular arms crossed, wearing a leopard pelt, he looks like Mandrake the Magician’s assistant Lothar.

Sex work? Well, with telepathy, everything’s free. But you could have a mind that really welcomed you in, and that might be different. Someone who is actually glad to see you. I’ve read that high-end prostitutes talk about johns wanting a GFE (girl friend experience). They won’t be hitting on little gnome Thu, but she’ll witness them trying to pick a guy up. Alternately, imagine a stuffed plush animal — not even a sex-toy — just an object that loves you and is glad to see you.

Art. A painting that decides what you want to see and shows you that. But I’m not supposing objects are all that smart. An object that simply projects the raw experience of transcendence or sense-of-wonder. Groundless euphoria, mindless pleasure, a vision of actual infinity. Or sensual beauty. Perhaps a rock that’s lain in a stream bed and you look at it and sense the lovely currents of the water.

Books? Maybe no books? I could suppose the telepaths won’t actually use language that much. But that would make them too alien, I think. So they have language for superficial small talk, but they more often use teeped images and emotions. They barely use the written language. Books are normally not written in words, they’re rather like hieroglyphs. A beautiful mind loop saved into the endless memory network, glyph by glyph. Writing is more like being a bas-relief sculptor. An array of teep tags. Perhaps there’s a book store like Metotem Metabooks run by a woman who’s just a bit like Darlene from the Lowbrane. And they let Thuy record her memories. Darlene gives Thuy a spice cookie, and she sees the Spice Islands.

Ads. Things projecting vibes of paranoia to get your attention. Or anger or lust or ecstasy: the whole palette of extreme emotions.