I just spent a week rereading William Gibson’s 2014 novel The Peripheral. Third time through. Mellowed out, lying on the couch, reading it on my Kindle, and highlighting passages that I liked…a nice thing about the Kindle, because then you can have the Kindle email you your highlighted passages in a single text file.

Sometimes I like to take one of these excerpts files and make it into a blog post, separating the quotes with photos from my stash, knowing that the photos will always, in a surrealist sense, go with the words.

I had quite a few old unposted photos, and I used almost all of them here. I put italicized captions on a very few of the photos. And I block-quoted the passages from The Peripheral. And I have comments after the quotes.

Worth reading The Peripheral now if you haven’t yet…the sequel, Agency, comes out in mid-Jan!

By the way I posted a little about the novel before, in 2017.

“It’s like wearing your cock ring to meet the pope, and making sure he sees it.”

A lot of the people in the novel are country, and they talk to each other in a funny way. This line is apropos of someone about to do something socially inappropriate.

Her head was perfectly still, eyes unblinking. He imagined her ego swimming up behind them, to peer at him suspiciously, something eel-like, larval, transparently boned.

This guy Netherton is observing a woman artist who he’s trying to scam. Her name is Daedra.

Classic anime robot babes, white china faces almost featureless.

The in-fact-horrific Michi assistant bots. Kind of perfect (ignorance) to call them babes.

Homes were all grinning and shit, after.

The “Homes” are “Homeland security cops”. And this guy Burton has attacked some people that none of them like, but the Homes have to arrest him, but… That’s a very Southern usage, “all grinning and shit,” and I love how Bill doles out this kind of dialog. I happened to meet our shared translator Daniele Brolli in Pisa, Italy, lately, and he was talking about how hard it had been for him to translate The Peripheral into Italian. It’s that writing-degree-zero, bare-bones, language-with-a-flat-tire slangy dialog.

Shaylene had big hair without actually having it, Flynne’s mother had once said.

Love this kind of subtle class distinction.

On the walls, the framed flayed hides of three of her most recent selves.

These are Daedra’s skins. She gets tattoos. There’s an echo of Marc Laidlaw’s novel The Thirty-Seventh Mandala. And Bill has another woman with moving tattoos, also a new SF trope used by a few others. But Bill tends to kick things up a notch.

“So what have you been doing?”

“Fucking the dog. Shot a bunch of pool, slept in the car, kept my ass off the street.”

That great flat-tire Southern style of talk.

It overtook and passed her as she reached the thirty-seventh floor. Moving that way, it no longer reminded her of a backpack, but of the black egg case of an almost-extinct animal called a skate, that she’d seen on a beach in South Carolina, an alien-looking rectangle with a single twisted horn at each corner. Tumbling straight up the building now, in a smooth sequence of sticky-footed somersaults. Caught itself with the two tips of whichever pair of horns, or legs, was leading, flipped over, then propelled itself higher with the pair it had just used to grip the surface.

So our heroine Flynne is observing, via a VR-like interface, a high-rise in some version of London. I love this thing she sees…our family used to find them on the beach in South Carolina.

“That’s why we can’t have anything nice,” she heard herself say, in the trailer.

This is such the classic thing a worn-down mother might say. Why even try, with kids like you.

Gloriously pre-posthuman. In a state of nature.

Netherton lives 70 years in the future, and he gets to see our legendary “Frontierland” days of, say, the 2020s.

The polt had told Lev that he was not, as it happened, a particularly easy target for a hired assassin.

The people in the future have an interface for talking to us. They even have us control “peripheral” bots of their own time. Peripheral meaning a device that you run. And the kicker here is that you might control a peripheral in the future, or a peripheral in the past, and in this fashion you achieve something like time travel. “Polt” is short for “poltergeist,” that is a spirit that makes noises and rattles things, so this is kind of a fit for an agent in the past who’s running a peripheral in your house. The polt in question is Flynne’s Marine vet Burton who is one very hardened guy. And this sentence is funny because it is such a vast understatement… “not, as it happened, a particularly easy target for a hired assassin.” And I love this sentence so much because by now I’m really rooting for Burton, and the people who will try to assassinate him are baddie whom I’m rooting against. Bill has the ability to conscript you and get you to buy into the morality tales in his books.

[Lady on a Cuba Day float in Manhattan, posing for selfies she’s taking before the parade…”selfies” in the sense that the has a friend who she’s using as a peripheral to run the phone. She’s from Jersey City.]

But since Lev had only touched her continuum for the first time a few months earlier, this Flynne would still be very like the real Flynne, the now old or dead Flynne, who’d been this young woman before the jackpot, then lived into it, or died in it as so many had. She wouldn’t yet have been changed by Lev’s intervention and whatever that would bring her.

Netherton the (good) scammer in the future is kind of in love with Flynne, the tough and intelligent country girl. They’re interacting via taking turns being in peripherals in the future or in the past. And Netherton is wondering how the “real” Flynne in his own timeline compares to the Flynne in the (inevitably forked off by now) timeline he’s changing. Lev is the guy Netherton works for. The “jackpot” is Gibson’s word for something like a really bad climate-change-crisis, somewhat alleviated by last-minute tech fixes.

[A bunch of drawings of our clan, done by the assembled grandchildren at a big family reunion this year. Versions of our timeline.]

“When we [first changed Flynne and Burton’s timeline] we entered into a fixed ratio of duration with their continuum: one to one. A given interval in the stub is the same interval here, from first instant of contact. We can no more know their future than we can know our own, except to assume that it ultimately isn’t going to be history as we know it. And, no, we don’t know why. It’s simply the way the server works, as far as we know.”

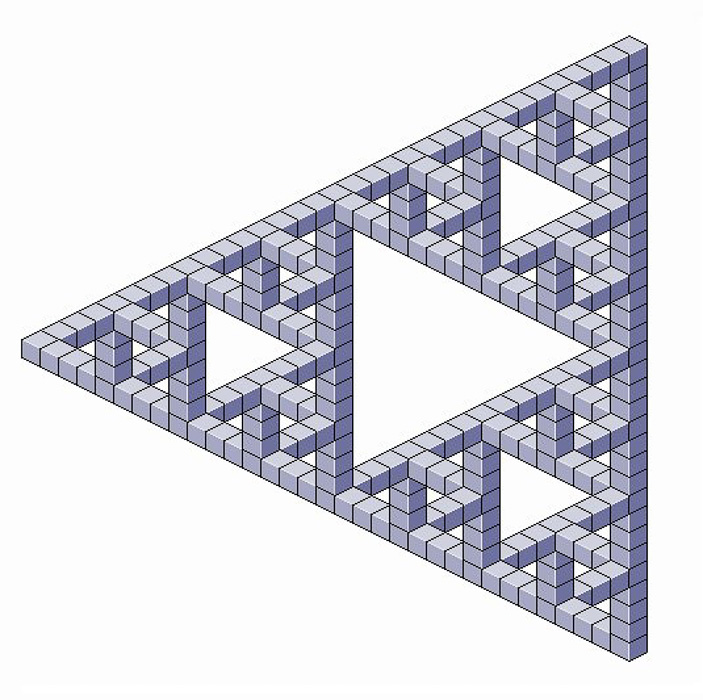

The timelines and the branched off “stub” timelines are called continuums, or rather, conitnua. Bill has really done his SF homework for this outing. This is where SF has an advantage over fantasy. If you go nailing down and bullshit-proofing and McGuffinizing all your rubber science, then it gives you ideas for more things to do and more probs to solve.

…the car cloaked itself, jigsaw pixels of reflected streetscape scrawling swiftly up the subdued gloss of its bodywork. Cloaked, it pulled away, seeming to bend the street around it as it went, and then was gone.

There’s this old woman in the future scene, like over a hundred, very wise, she’s called Lowbeer (a name somehow like that of Bill’s character Bigend). Bill gets you to buy into the idea that lowbeer is wonderful, heroic, infinitely cool. Somehow Bill is very good at this kind of thing, that is, enlisting the reader’s sympathyies. Lowbeer has a car that you can’t see, it “cloaks” itself by imitating the background. Another well-used SF trope, but done very nicely here.

There was Queen Anne’s lace grown up flat and level, a carpet of flowers, from the bottom of the roadside ditch, hiding the fact that there was a ditch at all. She must have walked past this spot hundreds of times, going to school, then coming back, but it hadn’t been a place.

Nice country landscape description. Bill grew up in a small town near Roanoke, Virginia, not so different from the environs of Louisville, Kentucky, where I grew up. “Got a silo fulla that country-boy corn,” as Burroughs might say. I love this stuff. As I boy, my friends and I used to pull up dried stalks of Queen Anne’s lace and hurl them, root end first, like spears. The twist in the passage here is this was just a spot like many others, but now that a quadruple killing (of bad guys) has taken place here, it’s a place. Nice distinction.

[Daughter Isabel in Mendocino; a shop where they sell gnarly hunks of wood.]

“It would be better to tell her the truth,” [said Netherton.]

Ash said nothing. Simply looked at him.

“What are you looking at?” [said Netherton.]

“I was wondering if you’ve ever said that before,” she said.

Ash is a Goth-type future woman who works with Netherton, the professional bullshit artist, osr PR man, whose job is conning people into doing things. He’s a lovable type, a heavy alcoholic who schemes constantly (and mostly unsuccessfully) to get a chance to drink as much as he wants to. This stuff is amusing and sypathetic for a former heavy drinker to read. Funny, mild put-down of Netherton here by Ash.

[This is an amazing time-related scene in the woods near where I live. Shadows of trees, more or less static, although slightly trembling with wind-chaos. Underneath them the steadily flowing of a waterfall. Like time, flowing under the matter that is the shadow. The last time I hiked in here, a Homes stopped me and gave me a ticket.]

And as he ran he screamed, maybe how he hadn’t screamed when what had happened to him had torn so much of his body off, but between the screams he whooped hoarsely, she guessed out of some unbearable joy or relief, just to run that way, have fingers, and that was harder to hear than the screams.

Okay, this is totally heartbreaking. Conner is another of the good guys, he’s also a Marines vet, but he has hardly any of his body remaining. One arm, one leg, and some fingers missing from the single remaining hand. And he gets to run a peripheral in the future, a very physically fit human-clone-type peripheral, it’s a boxing coach, and Connor gets in it and he starts running around in, like, huge underground concrete garage. And, dig it, the unbearable joy is harder to hear than the screams.

“Were you hearing voices?”

“Sort of trying to, you know? Just for something different to do?”

“Shit, Conner. Don’t be like that.”

Conner is grudgingly telling his friend Flynne about how fucked-up in the head is from being so physically damaged.

People were so fantastically boring.

Netherton the alkie, hip, sensitive bullshit artist in the future, summing up his world as he sees it from within his disease. If you’ve ever been like him, you know this feeling well. Actually you can even get this feeling when you’re sober…but there are ways out. Walk in the woods, do soemething creative, have empathy for someone, share love.

He was looking out at the peripherals in Impostor Syndrome again. Their fretful animatronic diorama…

Netherton has this gig where he has to hire a humanoid peripheral. The offline peripherals have low-level AI that lets them do things like hang out in a bar without talking much. Kind of there on display to be hired for use. The bar is called “Impostor Syndrome,” a condition which a lot of us writers and artists suffer from…the sense that we’re faking it, and we aren’t really writers and artists at all, we’re only pretending, and we’re scamming people, and in fact we don’t know how to write or make art, and it’s a miracle we’ve gotten by this long, but pretty damn soon the jig is going to be up. And here’s Netherton in the Impostor Syndrome, about to phone Daedra about a scam he’s running. Daedra, who really is more or less an imposter artist does not herself suffer from Imposter Syndrome. One supposes that the true imposters never do. The lower your abilities, the greater your confidence.

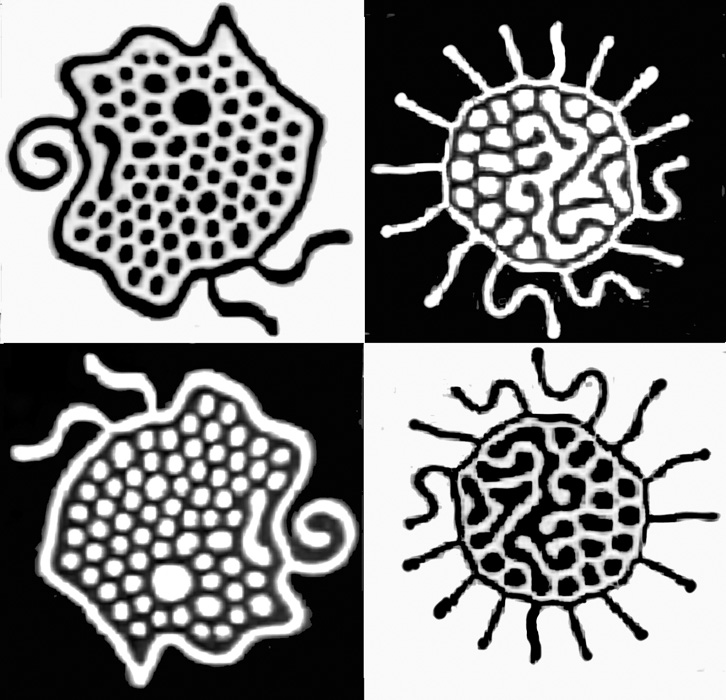

[These patterns were generated by something like rotating magnetic fields. Magnetohydrodynamics. I randomly saw them a journal, and then I copied them in color for a diptych painting.]

Ash produced the Medici. She pressed it against the black fabric of his jacket, above the injured shoulder, and released it. It stayed there, quickly ballooning, then sagging, worryingly scrotal, unevenly translucent, and doing whatever it was doing through the black jacket, which somehow made Netherton particularly queasy. He could see blood and perhaps tissue whirling dimly within it. It was larger than Ossian’s head now. He looked away.

Dig this future medicine. It’s full of nanobots called “assemblers” that can move your molecules around one at a time. Love the phrase “worryingly scrotal.” In the presence of that adjective, the adverb almost goes without saying, but it’s so funny to say it.

“We carve history from totalities beyond our grasp. Bolt labels on the result. Handles. Then speak of the handles as though they were things in themselves.”

Yeah. Like the Sixties, the Eighties, Cyberpunk, Gen X, World War II, the Elightenment, the Dark Ages, Ancient Egyt, the Trump Years.

…a state Netherton found unimaginable. The world seemed to consist increasingly of such states.

Love Netherton’s anomie and his despair over his inability to exprience whatever state he’s talking about. He is so terminally other.

“My hairy arse,” said Ossian, as if naming the root precept of a long-held philosophy…

The joy of lower-class vulgarity. Nostalgie de la boue. Relishing lower companions. And the elevation to long-held philosophy.

“No hot synthetic bods, back here in Frontierland,” she said, “but we got Wheelie Boy.”

Her room, rotating the cam as far as he could, was like the interior of some nomadic yurt. Nondescript furniture, tumuli of clothing, printed matter. This actual moment in the past, decades before his birth. A world he’d imagined, but now, somehow, in its reality, unimaginable.

Wheelie Boy is this toy that Netherton uses as his peripheral back in our approximate era. So funny to that word Frontierland, a riff off Disneyland. Such a corny word. And here we are, in Frontierland, but feeling it as real and not a jape. Like the twisted peasants in a Bruegel painting. And our present is a subject for Netherton’s future nostalgia for the unreachable past of his elders. I yearn for the 1940s (decade of my birth) in just this way. The bouncy swing music, the women’s waterfall hair, the tough-talking, the down home Norman Rockwell of it all. I’m a salmon looking to swim up time’s river to my birth. Gibson’s passage also evokes that flash you get, now and then, possibly while on powerful drugs, that this, your daily life, is really going on. And it takes so much effort to simply wake up and see this. D’oh!

Just everything else, tangled in the changing climate: droughts, water shortages, crop failures, honeybees gone like they almost were now, collapse of other keystone species, every last alpha predator gone, antibiotics doing even less than they already did, diseases that were never quite the one big pandemic but big enough to be historic events in themselves. And all of it around people: how people were, how many of them there were, how they’d changed things just by being there.

Summary of how the “jackpot” trashed the world and killed most of the people. And this horrible, growing realization that it may be actually in store.

But science, he said, had been the wild card, the twist. With everything stumbling deeper into a ditch of shit, history itself become a slaughterhouse, science had started popping. Not all at once, no one big heroic thing, but there were cleaner, cheaper energy sources, more effective ways to get carbon out of the air, new drugs that did what antibiotics had done before, nanotechnology that was more than just car paint that healed itself or camo crawling on a ball cap. Ways to print food that required much less in the way of actual food to begin with. So everything, however deeply fucked in general, was lit increasingly by the new, by things that made people blink and sit up, but then the rest of it would just go on, deeper into the ditch. A progress accompanied by constant violence, he said, by sufferings unimaginable. She felt him stretch past that, to the future where he lived, then pull himself there, quick, unwilling to describe the worst of what had happened, would happen.

But we can hope that science will save our asses yet again. That’s the bright side of SF. Dreaming a sunny tomorrow. And why shouldn’t it be possible. There’s so much stuff we haven’t discovered yet. Look how far we’ve come already.

“It is,” said Lowbeer, “as people used to say, to my unending annoyance, what it is.”

When I first heard a hip friend of mine say “It is what it is,” back in 1986, I thought—Wow, what a cool way to put it, what a philosophy, how deep is the acceptance, the jaded wisdom. But the hundredth or thousandth time you hear it, the thrill is gone. And the stilted way this character is making that point is a gas.

“I’ve seldom found the results particularly useful, myself, as thematically interesting as primary oneirics can be. Though mainly in how visually banal they generally are, as opposed to the considerable glamor we all seem to imagine they had, as we remember them.”

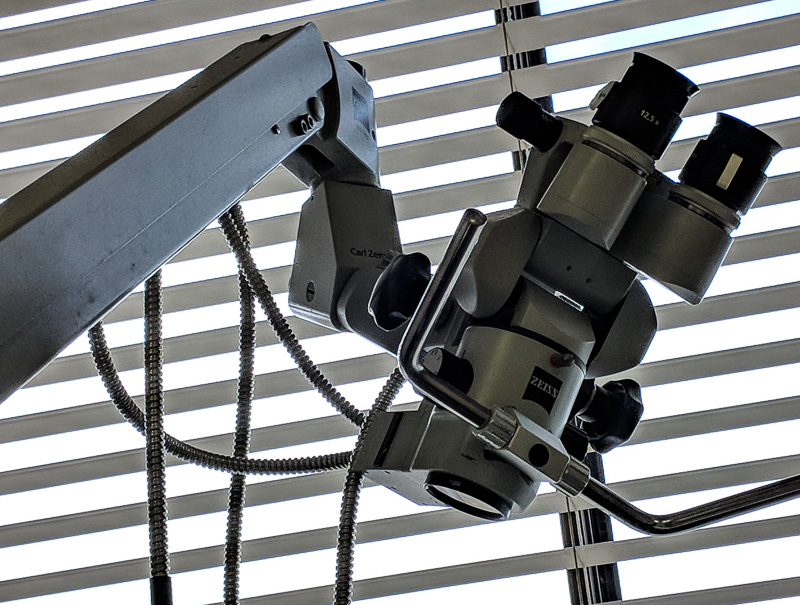

This is Lowbeer talking about the usefulness (or not) of using their near-telepathic mind monitoring techniques to see people’s dreams. “Primary oneirics” being the study of raw dreams. And I think it’s a good point that the visuals of our dreams are not in fact very elaborate. You’re moved more by the emotional weight that you put onto a dream object.

The spidery figure, she guessed, would be close to ten feet tall. “A peripheral,” he said. The tall thing’s round pink head was fronted with a sort of squared-off trumpet, that same pink, through which it blared down, incomprehensibly, at the small crowd of figures surrounding it, at least one of which seemed to be a penguin, though as tall as she was.

Pure artistic license here, sketching surreal imagery. Eyeball kicks.

But the water in the region of the battle had scaled waves, and miniature cloud,…

One of the big probs in making movies in the past was that, if you want to show a ship in a storm and you faked it by showing a one-foot model ship in a sloshing laundry tub, then the waves wouldn’t…look right. There are complex issue about the way that smaller hydrodynamic systems fail to emulate larger-sized ones. The turbulence only looks the same of the two systems have the same Reynolds number, and I barely understand what the Reynolds number is. Thomas Pynchon name-drops it in Gravity’s Rainbow, and that’s how poeple like Bill and me know about it. I think maybe you could make a tub of liquid have a Reynolds number like an ocean bay if you did something funky like make the wash tub be full of a really dense or less viscous fluid…I need to read up on it some day. But, as an SF writer, Bill, who knows all this, just punts on the problem, and presents the solution as a fait accompli in the special toy pond in this London park.

There were, for instance, Ash said, continua enthusiasts who’d been at it for several years longer than Lev, some of whom had conducted deliberate experiments on multiple continua, testing them sometimes to destruction, insofar as their human populations were concerned. One of these early enthusiasts, in Berlin, known to the community only as “Vespasian,” was a weapons fetishist, famously sadistic in his treatment of the inhabitants of his continua, whom he set against one another in grinding, interminable, essentially pointless combat, harvesting the weaponry evolved, though some too specialized to be of use outside whatever baroque scenario had produced it.

These kinky futurians are reaching back in time and stubbing off timelines (or continua) and effin with them. Kind of like a whole Stan Lem A Perfect Vacuum imaginary novel in this paragraph.

[Flynne:]“You don’t hang out a lot with artists?”

[Netherton:] “I don’t, no.”

[Flynne:] “I would, if I could.

Flynne’s touching, heartfelt yearning to be a part of an art scene, and to mix with interesting people. The country mouse’s longing to be in the city. And Netherton, who could do it, doesn’t bother or, knowing the natures of artists better than Flynne, doesn’t want to.

It was like the pictures in a box at a yard sale, nobody remembering who those people were, or even whose family, let alone how they came to be there. It gave her a sense of things falling, down some hole that had no bottom. Whole worlds falling, and maybe hers too…

Those photos of ancestors that your parents had, you’re looking through them while cleaning out the parents’ houses after they die, all these layers of time, like compost on a forest floor, no end to it.

“The aunties, continually mulling it over. A process akin to repetitious dreaming, or the protracted spinning of a given fiction. Not that they’re invariably correct, but over a sufficient course they do tend to find the likely suspects….A process akin to repetitious dreaming, or the protracted spinning of a given fiction.”

So much of the writing process is unconscious. That’s what we mean by waiting for the muse. Too many possible plot branches to logically explore. The thicket too dense. You dream the story while you’re awake.

“I’m in the future that would result from my not being there. But since I am, it isn’t your future.

Time Paradox solved. I discuss this with some diagrams in another 2017 post of mine that mentions The Peripheral.

He turned the camera, studying the shabby, shadowy tableau of lost domestic calm.

Endless nostalgia for the past. That’s one of the things time travel stories are about.

“Playing soldier?”

“They were all in the service, before.”

“Think they’d’ve got their fill of it,” her mother said.

Burton and his old Corps buddies are protecting their family. The mother has the female POV on this.

“You’re someone who only pretends to be unintelligent,” Netherton said. “It serves you simultaneously as protective coloration and a medium for passive aggression. It won’t work with me.”

I’ve known a number of people like this. They play the diamond in the rough, the last honest one, the plain-spoken sage. Interesting to see Netherton directly call someone on it. Not that the call is likely to work.

[Two or three years ago my hip was really screwed up, and I could hardly walk, even with crutches, and I’d take a fifty-yard outing-walk every few days, a walk along a level path to this big fat log, and I’d sit on it, and be happy to be outside, and not in the hospital. My leg’s better now.]

“West’s oeuvre obliquely propels the viewer through an elaborately finite set of iterations, skeins of carnal memory manifesting an exquisite tenderness, but delimited by our mythologies of the real, of body. It isn’t about who we are now, but about who we would be, the other.”

This passage is some robo-BS generated by a bundle implanted in Flynne’s future peripheral. It’s supposed to impress the artist Daedra, the woman who tattoos her skin, then has herself peeled, and sells the skin. She’s done it more than a dozen times. Bill is having fun emulating high mandarin lit crit here. I’m sure they’ve written things like this about his work.

Records, during the deeper jackpot, are incomplete to nonexistent, and more so in the United States. There was a military government there, briefly, that erased huge swathes of data, seemingly at random, no one seems to know why.

Why did I assemble this blog post? No real reason. Just for fun. And wanting to formulate and share some thoughts provoked by G’s masterpiece. Hope you enjoyed! Happy holidays.