Time to catch up on my photos. Here’s May and June, 2025. A lot happened.

Here I am in North Beach with Barb, back in May. Love the display sign of a big fish!

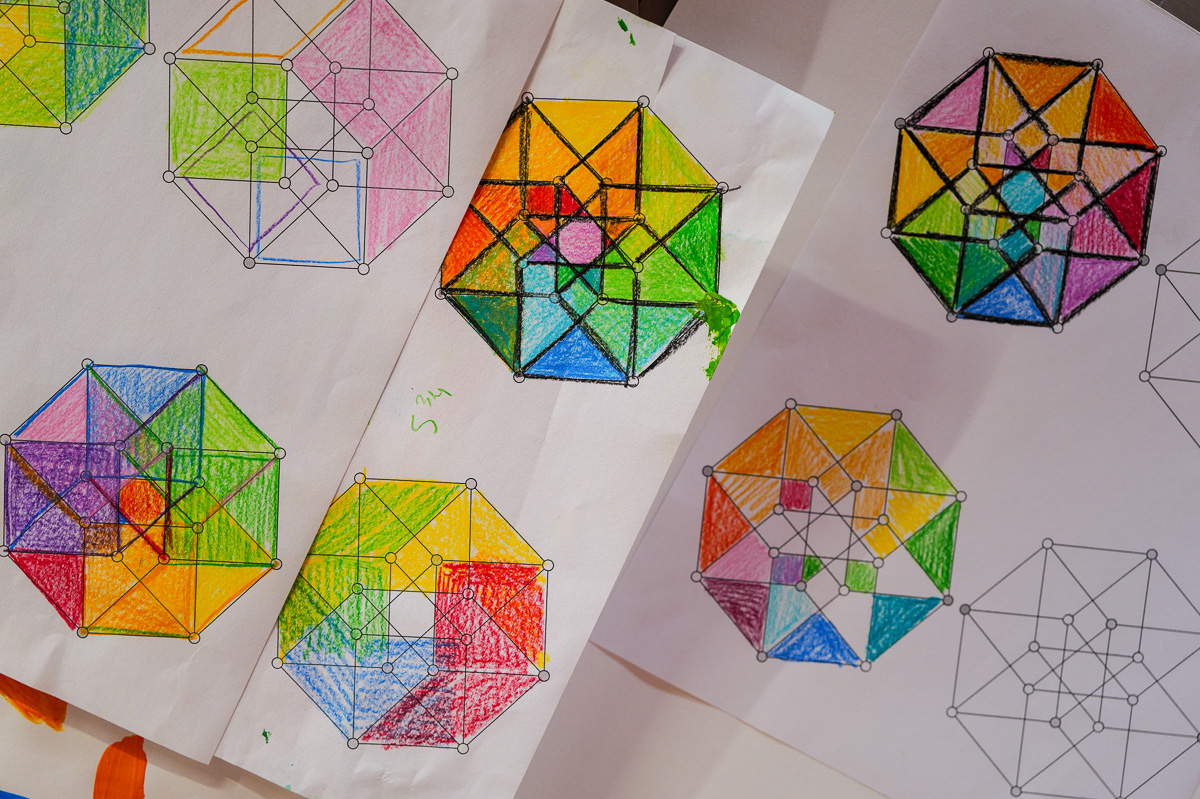

Fab four-color fan. Usually I line myself up so that the horizontals and verticals are straight, but this time I got crazy and went off on an angle, and it looks better.

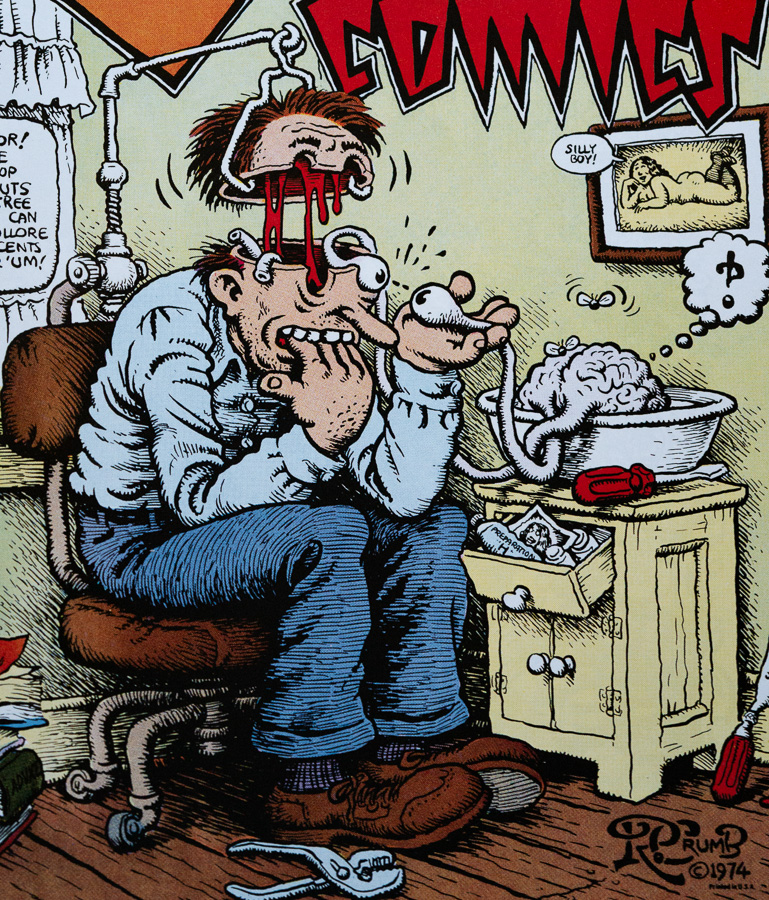

I happened to read the excellent new biography of cartoonist and folk-hero R. Crumb. Great book. And he’s a long-time hero of mine. I dug out my collected Zap Comix and came across this truly wonderful cover by our man. Like you’re halfway through doing something crazy, and then you forget how to finish.

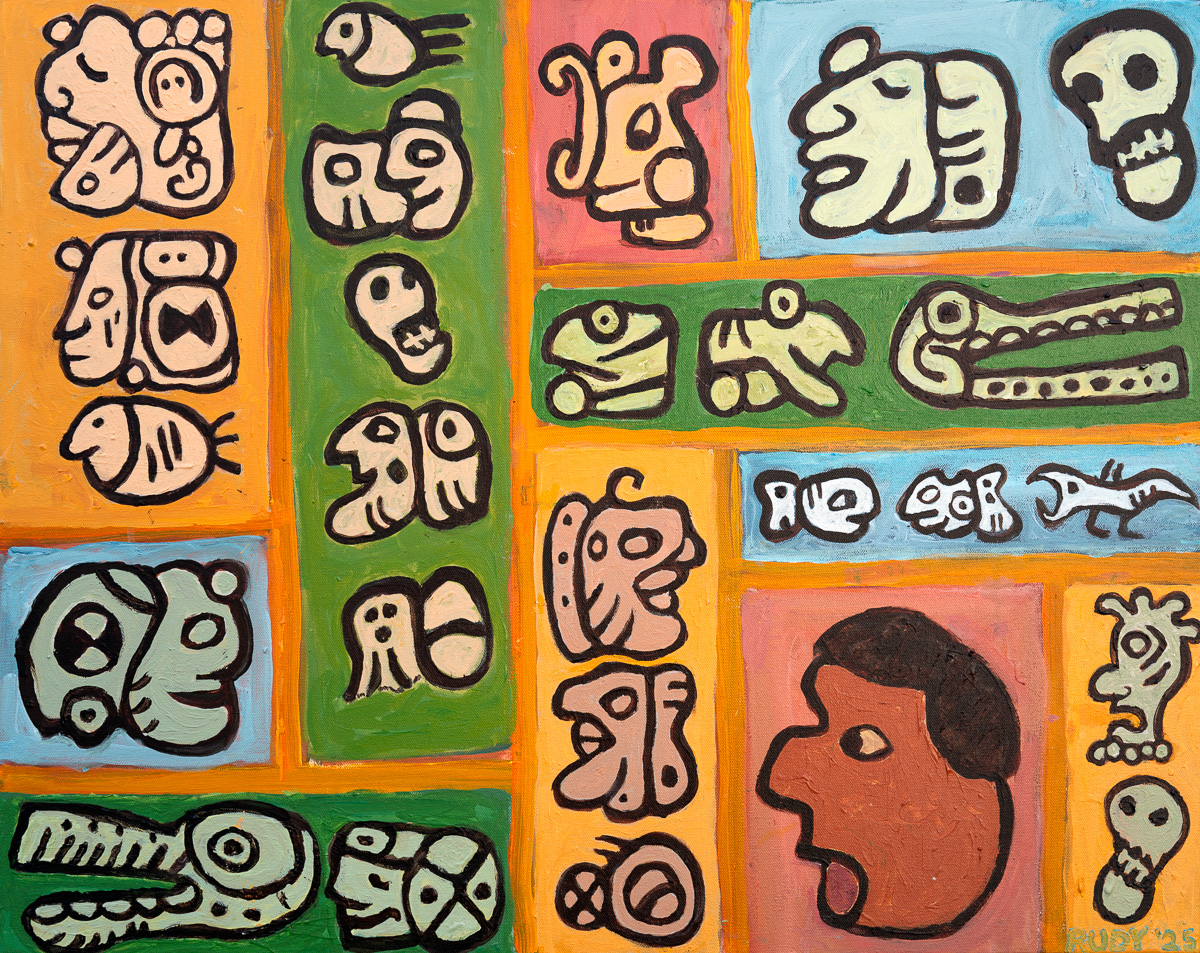

Another Rudy painting. And Another f*cking masterpiece as I like to say. AFM for short.

I’m imagining a pair of lovers spiraling down toward—a cosmic gateway? Ultimate ecstasy? Who knows. They look like they’re getting a little smoother on the way down, like rocks tumbled in the sea. I like the way the two lovers are cruising along. I did the yellow background with finger-painting, an effect I sometimes use. That is, I squirted blobs of four different yellows and smeared them around, wearing my latex painting gloves.

Getting the right reds and blues for the lovers took me some time. Shade, saturation, and value—all three have to be in harmony. Another challenge for The Lovers was to get the geometry right! I would say they’re moving along a helix that has increasing torsion—in the sense of being more and more stretched out, like a Slinky being pulled straight. I worked it out by eye, with plenty of do-overs.

I’ve been painting a lot over the last few months. Sometimes I go right from one to the next, using whatever I see as inspiration. I did the one after Barb and I visited the Monterey Bay Aquarium once again. We went straight to the octopus tank. Instead of lurking in a corner, the creature was right up against the glass, with a zillion suckers attached, head hanging down like a blank blob.

I called the painting “Here I Come.” And I gave it some strange eyes…not really accurate for octopus eyes, but I wanted the sense that it’s looking at you.

Making a tough-guy face in the mirror for a photo. I’ve been doing this since I was sixteen. I call these my “Wall Street” pyjamas.

Gary Hughes is an artist friend of mine who lives in Santa Cruz. He’s a very unusual person. He’s in the “Church of the Subgenius” and is a friend of Paul Mavrides, as am I. He and his research biotech scientist wife live quite near the beach and they go surfing every day. He ran a sign-painting shop in Oakland for a number of years. His paintings are incredibly intricate and take months to complete. You can find some people with his name online, but most of them aren’t him. Here’s his awesome website.

We had a big family together that ran across two weeks. Rudy Jr’s twins Jasper and Zimry were graduating from high-school. Here’s Jasper with mother Penny at Jasper’s graduation.

Here’s grandpa being a flower child.

A sample of the great WPA murals inside Coit Tower. Reading comics!

Grandaughter Zimry in her graduation robe, and wearing a family signet ring.

My girlfriend Barb was along for the event. She and I stayed in a really good and inexpensive old-school motel in North Beach at the edge of Chinatown. The Royal Pacific. We like to dance, it’s near the Saloon, which is the oldest saloon in San Francisco. They have two great live bands every day. They’re on Grant Street, half a block uphill from Columbus.

This is what Barb and I call a “Rudy photo.” I’ve been taking these for yours. Barb is a big photographer—she posts on various stock photo sites—and we enjoy walking around shooting, and discussing our shots.

Here, once again, I’m painting for the sake of painting, and emptying my mind. Waiting to see what develops. I ended up with something like a rose bush, and you’re looking up through it toward the sky. Even though, okay, there’s no main “trunk” on the bush. It also reminds me of how much I like to lie under a tree and look up through it, a traditionally decorated home Christmas tree in particular, and, come to think of it, that could be a whole other painting. To give this one more texture, I added thorns, and shading on the roses, and then bumblebees. The three green breaches might also be thought of as a woman jogging to the left. And of course the title is goof on the band name, Guns ”˜N Roses. I’ll take whatever the Muse gives me!

Isabel had an art show opening up in Fort Bragg, California, just north of Mendocino. Georgia, Rudy Jr, and I made our way up north for the show after the graduations. I got a cool panorama shot with Isabel’s husband Gus in the mix as well. Each of the kids appearing more than once. Check out Isabel’s

site.

Isabel took us to an amazing spot in the redwoods. Love this waterfall. I used a fast shutter speed, and a vignette effect around the edges.

My three children. All over fifty now. Life is amazing.

![]()

Found this sweet sand-art piece on the beach.

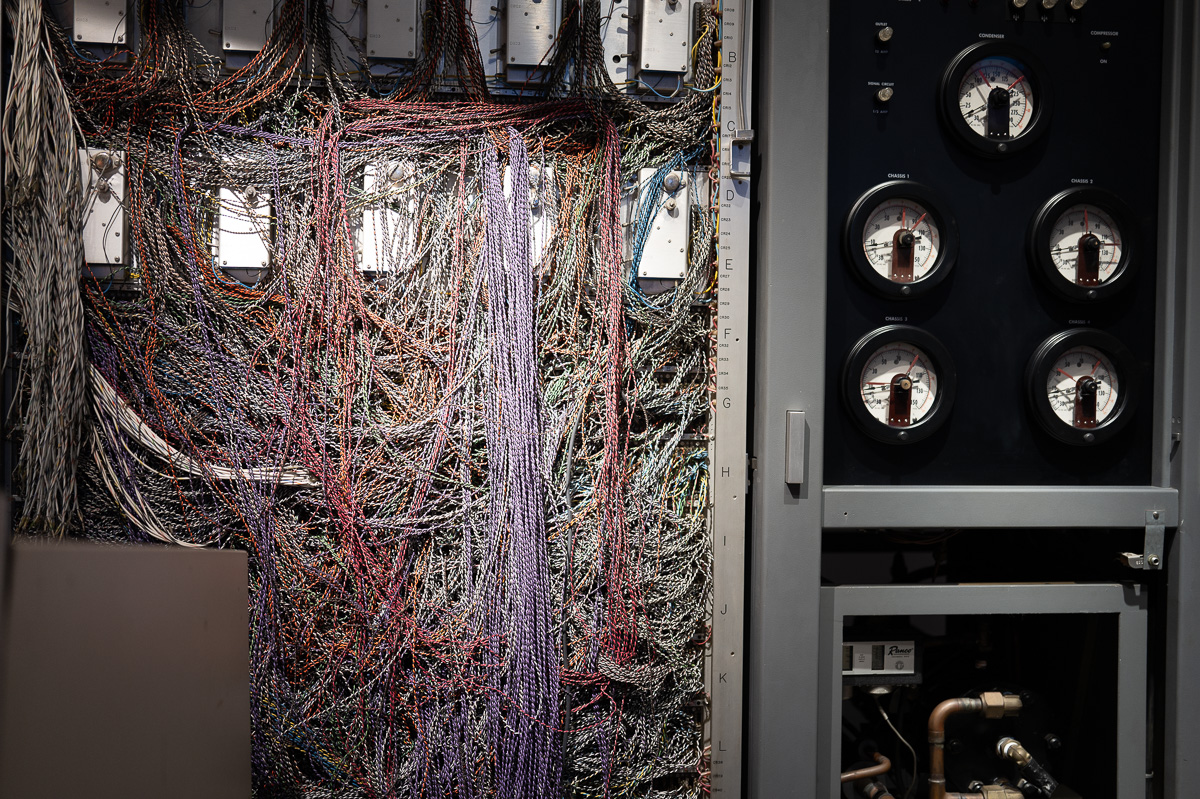

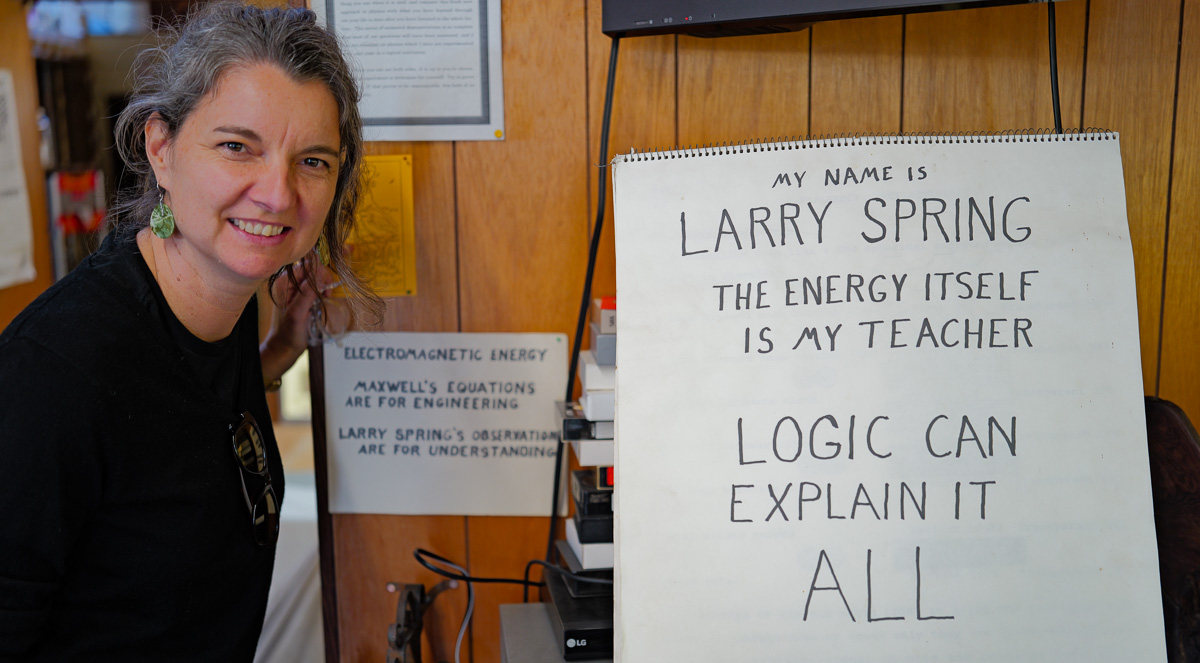

My old running-mate R. U. Sirius (aka Ken Goffman) put together some kind of show or festival in the Grey Area building, formely a Mission movie theater. I knpw R. U. from the Mondo 2000 days. I actually helped edit their big best-of compilation, Mondo 2000: A User’s Guide to the New Edge. How to organize the chatoic sea of excerpts? I gave each one a title and put them in alphabetical order. And I made sure they paid me before I started work.

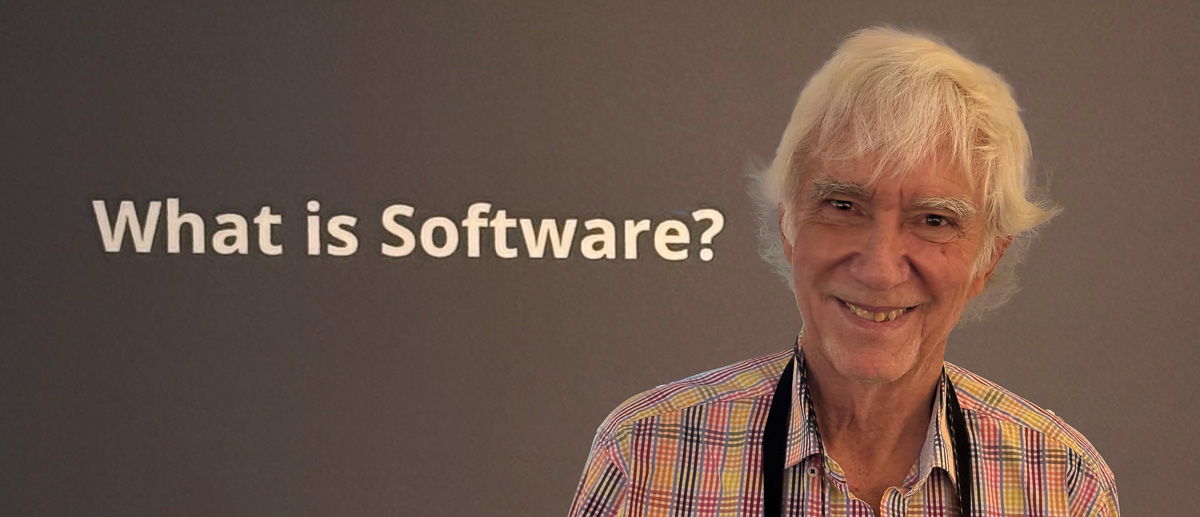

At the get-together, I read a transreal story about an eccentric SF author. “I Arise Again.” It was a very noisy crowd, especially from the folks in the back. I think it’s possible that some of them were…high?

A few days after all this, Barb and I took off for a week in New York, staying in Manhattan near Madison Square Park, which has become a very civilized and pleasant spot. It’s next to the classic triangular Flatiron building…which was the home of my SF publishers Tor Books during the heyday of my career. A number of classy stores along Broadway here, including ABC Carpet, wheein this man is changing a lightbulb in dizzying space. In the 1800s this block was called the Ladies Mile, as it was suitable for shopping.

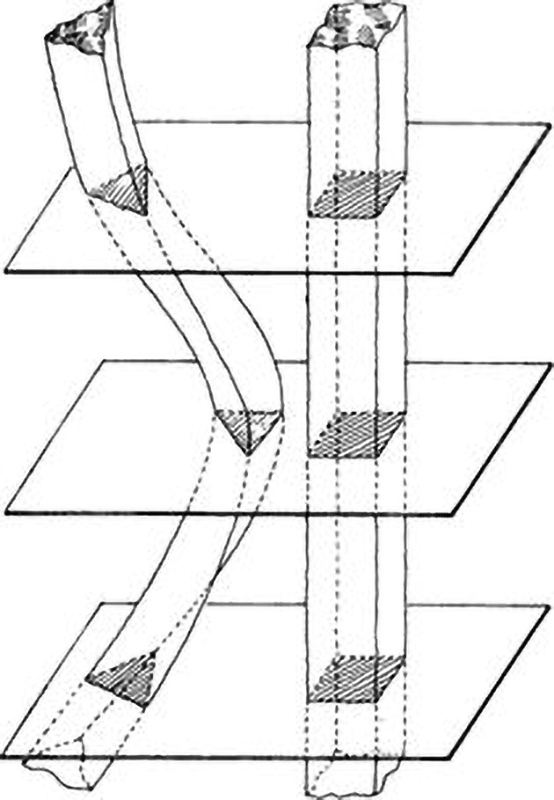

Barb was curious about the ubiquitous “steam stacks” to be found in the streets of NY. I’ve seen them my whole life, but didn’t in fact know what they’re for. Turns out the cunning natives like to use a single power plant to heat several large building as once. Live steam is channeled to a bunch of buildings from a single monster furnace. And for whatever reason, plumes of extra steam may need to be released here and there.

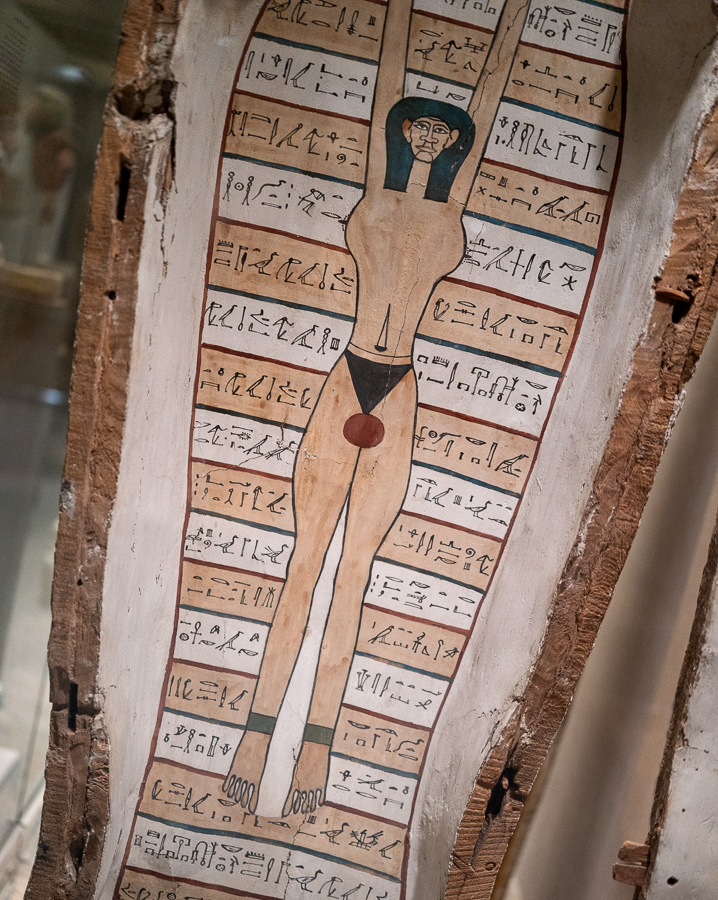

We hit the Met, saw the van Goghs, then headed to the insanely great Egyptian wing. I tend not to see Egyptian art very often, and can forget how stunning it is. We, like, think we invented modern art in the 1800s, but let’s try a thousand years BC! This little goddess is called Hathor, and is sometimes found on pillars. I love her elfin, triangular face. Up for anything.

Anything at all! Turns out Hathor is associated with the god Atum, who is said to have created the universe by masturbating. And there’s a special goddess associated with Atum’s hand. She has various names…but one of them Hathor!

“Hi boys, I just got in from Memphis. Any of y’all want to have a good time?”

This stone crypt looks like it weighs ten tons. And, yeah, it’s three thousand years old. They knew how to build things to last, those Egyptians.

This drawing seens to be on the inner surface of a sarcophagus. Looking at it, the modernity of Egyptian art really hits you. This drawing could be in a zine or graphic novel printed this week. Why the red dot? Is she shackled down? Is she human or a god? Queries for today’s zine.

Speaking of women, here’s a nice shot of Barb. She was really enjoying herself at the Met.

Love the eyes. Like…why do we even bother to try and make art after the Egyptians? Oh, well, what else is there to do! More art, forever.

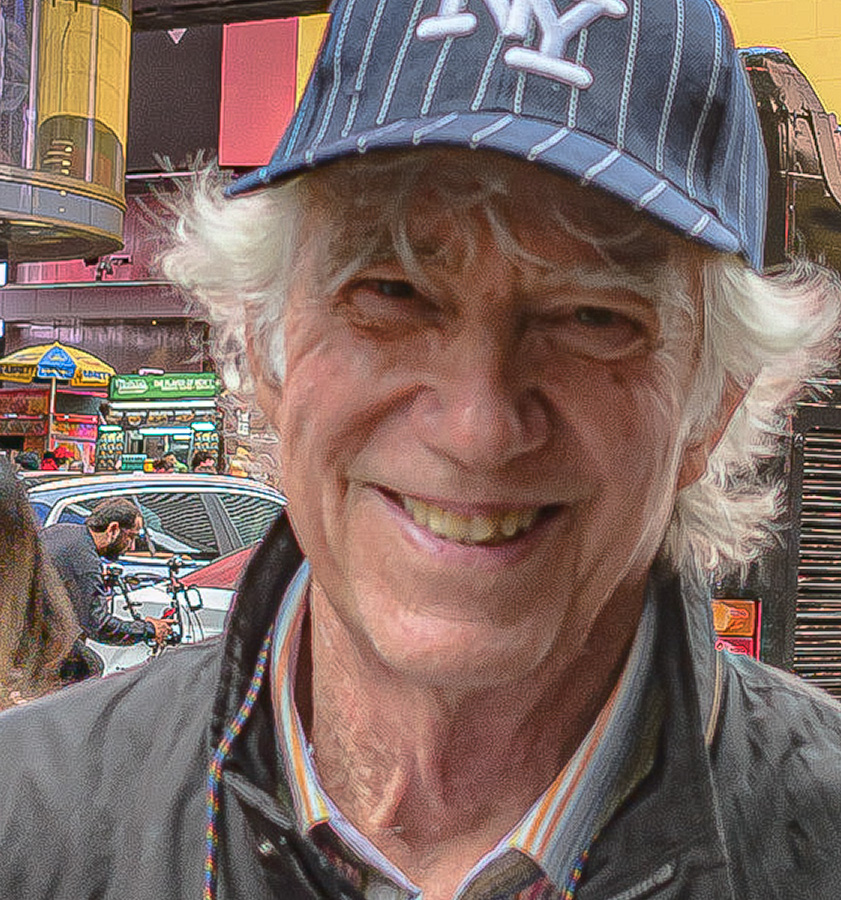

Our Uber was passing through Times Square, so we jumped out. Gotta show this to Barb. She’s a California girl, with relatives in the NY boroughs, but she’s never done Manhattan. The lights get smoother every years. It was raining…I bought a cheap hat in one of the souvenir stores, a Yankees hat no less. Perfection.

In my college days, they were starting to send guys my age off to die in Viet Nam for no good reason at all. Sometimes we’d be in New York and we’d check out the skeevy scene in Times Square — as it was back then. An unforgettable Army recruiting booth stood in the square, adorned with an electric flag … and it’s still there. I always had this fear that the booth might get me. Like I’d be drunk and stoned in the city, and heart-broken over something like a lost love, and just before dawn I’d stagger into the booth — and they’d sign me up, and it’d be next stop is ‘Nam.

But the booth never got me. And eventually I had job teaching computer science to Vietnamese students at San Jose State University. I got to like them a lot. Even so, the booth still awaits. Gives me a shiver just be near it. Like I’m a lobster near a lobster trap.

We visited ground zero as well, with Maya Lin’s stunning “footprint” monuments. Two vast square holes matcthing the bases of the gone towers. Water flows down from the top of each hole, like tears, down into a big pool, and into a black square hole in the center. (The central hole doesn’t show in this photo.) The central hole is like death’s door. Incredible.

And the new tower soars upward, lost in the mist.

Wall Street a must-see as well. Love all that heavy old stone in these structures. The epitome of solidity. What’s even inside there anymore? Isn’t it all in the cloud?

An odd French luxury department store right by the Stock Exchange. Printemps (means spring). I liked the magic soft chair with red light.

Near Wall Street stands a large statue of a brass bull. Symbol of financial gain, as in bull and bear market. This bull has a big pair of brass balls. An extremely large and animated crowd seethed around the bull, taking turns photographing each other in the act of caressing the balls. What word might adequately describe these jubilant tourists waiting in line for their photo ops?

I wanted to show Barb the Battery, that is, the shore at the lower end of Manhattan — but it was completely fenced off. Seems that, ever since the monster storm last year, with its ten-foot waves, the NYC engineers have been constructing some kind of flood wall. So now you get down there and you can’t see. No fond touches of that classic film Desperately Seeking Susan.

By standing on a bench by a chain link fence next to a tour-boat boarding ramp, I did manage capture an image of our good old Statue of Liberty. Protect us, dear Lady.

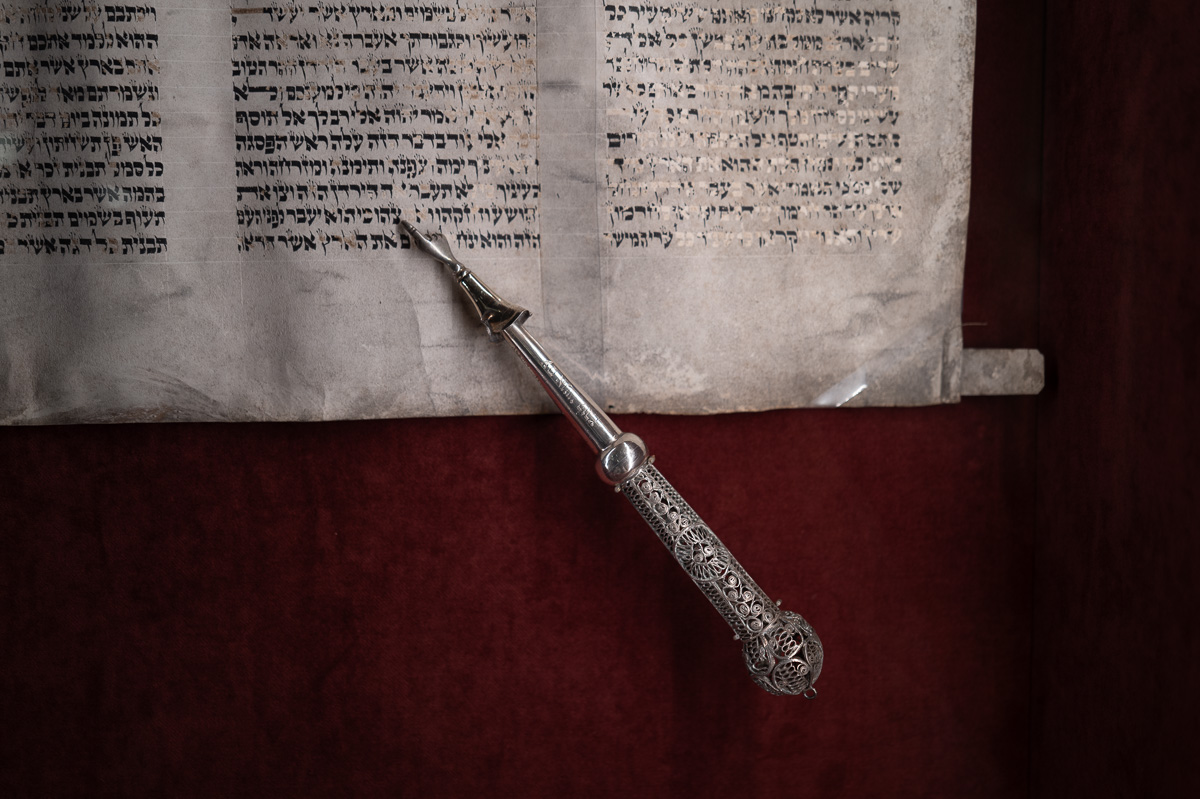

Barg has an interest in photographing synagogues. We made our way to the Lower East side where a synagogue functions also a museum of the history of the Lower East side. Wonderful interior.

We saw a display of torah-related items, and I was struck by this pointer, called a yad. You’re not supposed to touch the torah when you read from it, so you have a yad to guide your eyes. Great word.

Eventually we made our way to the wonderful NY MOMA. The piece here is a slice of a house, mounted as an artwork. Playful Barb is pretending to walk up the slice of stairs.

Then up to the Plaza Hotel on Fifth Ave by Central Park. Dig the mysterious man with a briefcase in the steam stack fog.

A perhaps annoying new feature of the city is the prevalence of these new “pencil” or “needle” buildings. Ten or fifteen years ago there were only a few of them, but now they’re all over. Like porcupine quills. Each floor holds, I suppose, one or two condos for the ultra-rich. The locals insist that hardly anyone actually lives in the condos. They own them as investments, or vacation spots. Somehow this reminds me of crypto cash.

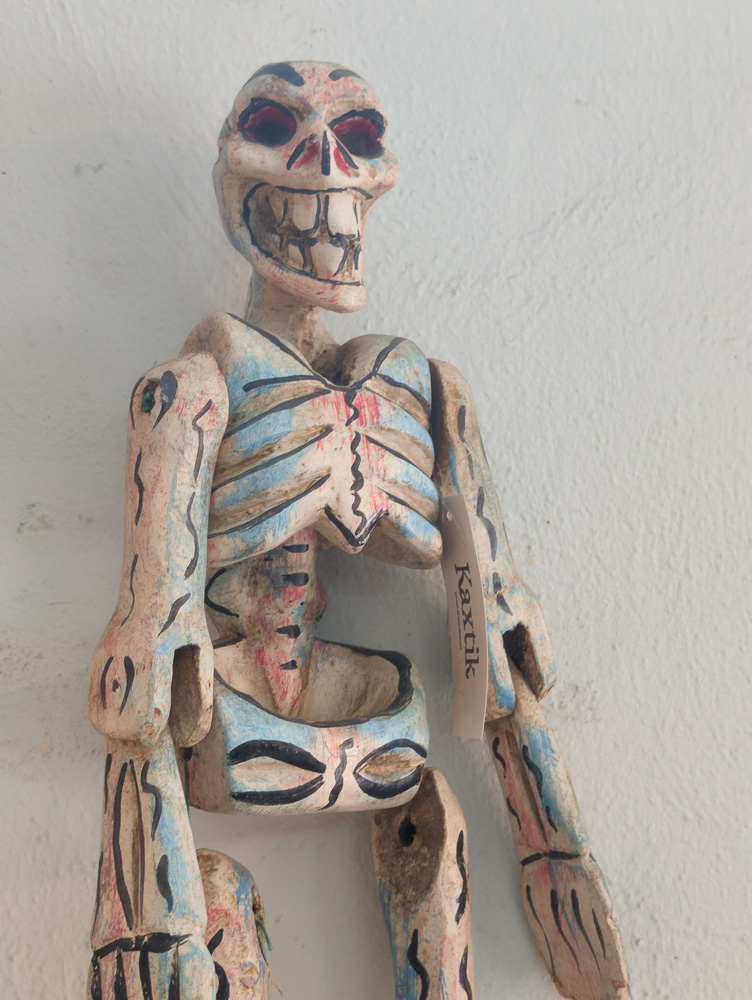

Walking along Saint Mark’s place in the East Village, Barb and I saw a great Nepalese god mask…I forget the name of the god in question. Rudy?

We were down there to have lunch at the classic Ukrainian restaurant Veselka. We met an old SF pal of mine, Ellen Datlow, one-time editor of OMNI, and known for the horror anthologies she edits. What with the deaths of my long-term agent Susan Protter, my editor Dave Hartwell, and my fellow Kentucky beatnik SF writer Terry Bisson — Ellen’s the one! It was cozy to be with her.

Here I am with my college pal Roger Shatzkin, on the top floor of the Whitney museum. Seems like I meet Roger at the Whitney every year. It’s comforting. But how the f*ck did we get to be eighty?

Barb and me in the same spot. I may be eighty (more or less), but life is still good. After lunch we two walked on the insanely futuristic High Line, a walkway buitl in place of an old elevated railroad track.

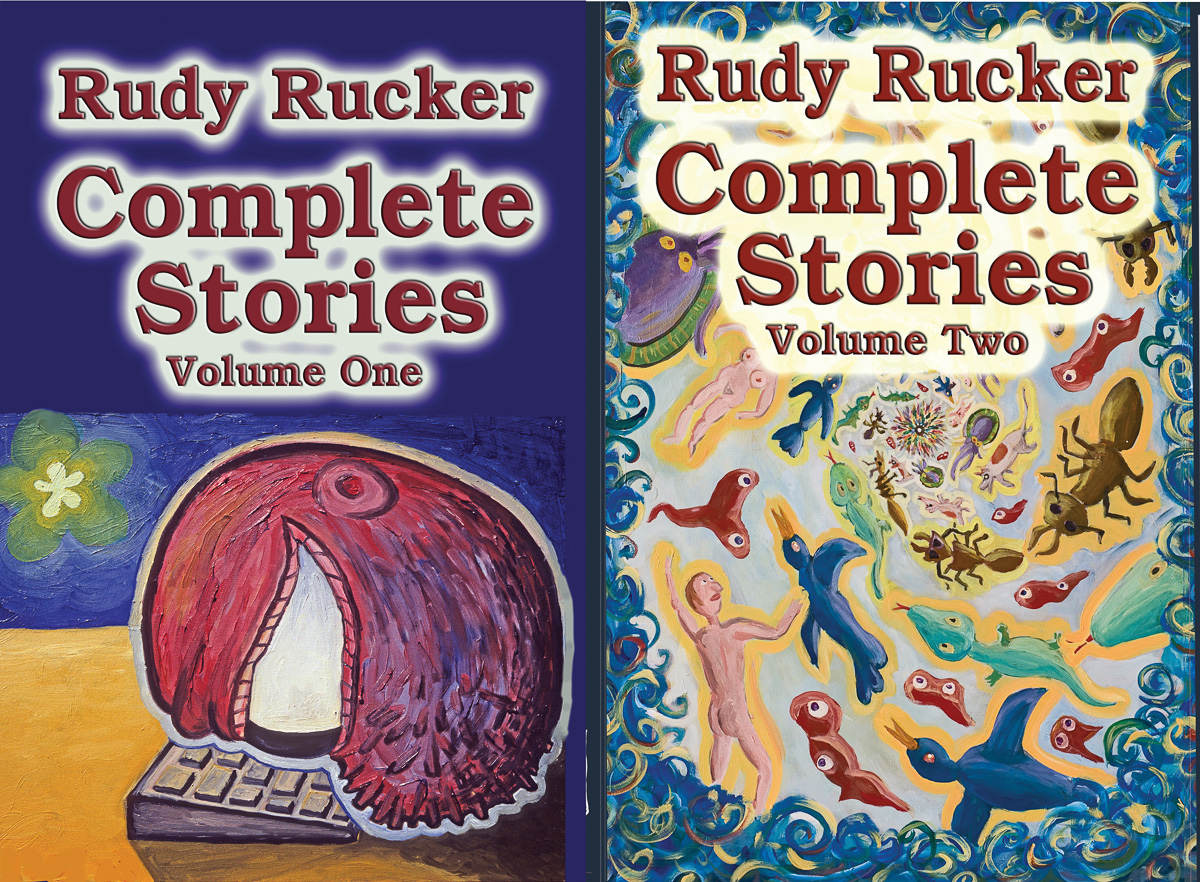

And we checked in with my current literary agent John Silbersack as well. As always he took us to a classy NYC club, and as always these days, his assessment of my literary prospects was less than salubrious. Long story short, he feels I might as well self-publish my recent masterpiece novel Skinks. A small press would pay no advance and sell only about five hundred copies. Plus I’d have to wait on line for a couple of years, and they might use a bad book design. So I’m thinking that, as I’ve done before, I’ll do a Kickstarter for the new novel and publish it under my Transreal Books imprint. Watch this space!

Back at home I did a new painting. “Hvalfisk.” Abstraction again. Color harmony. I added the two eye-circles at the end of my process. I always like painting eyes and flying saucers and tentacles. And once the eyes were in place, I was thinking of sea creatures or, more specifically, whales. The title? In Norwegian, “hvalfisk” means “hval fisk” or “whale fish,” or simply “whale.” And this happens to be a word I sometimes like to yell when I’m alone on the beach, using the accent of my Norwegian friend Gunnar. See my curiously neglected video, What Is Gnarl? .

The video is from, wow, eighteen years ago. I was so much smarter then, I’m dumber than that now.

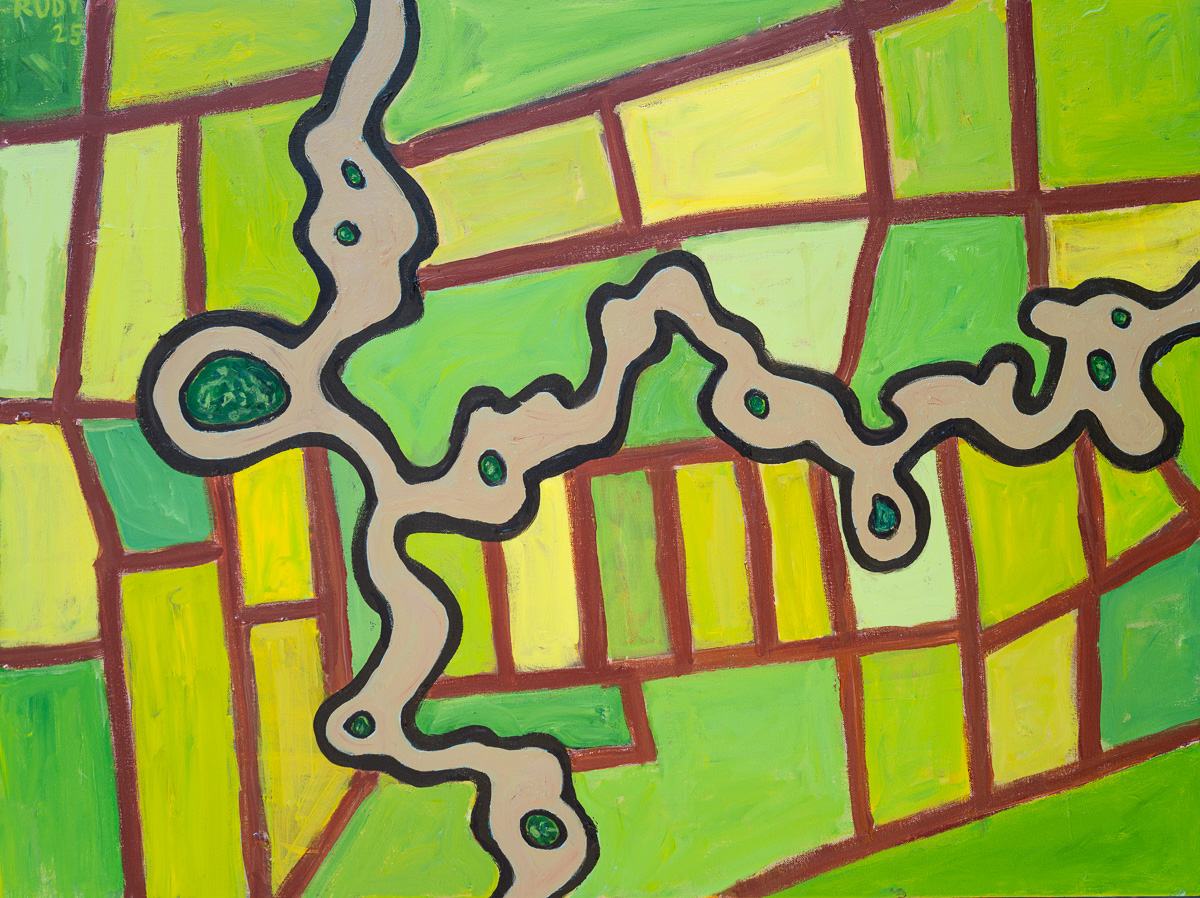

I saw this view from a plane while flying east from San Francisco at the start of our trip. Passing over the Sacramento”“San Joaquin River Delta. The multifarious winding streams in this area have oxbows, that is, bulges where the river may or may not pinch off into an oxbow lake. Fan of gnarl that I am, I love looking down at this area from a plane. And I got a photo.

And after the trip I painted the hoto. The supreme modern California artist Wayne Thiebaud painted this region many times. But it’s an inexhaustible motif. One thing I like here is the contrast between the orderly polygonal fields and the twisty river streams—mirroring the split between the digital and the analog, the computer and the soul, the word and the image. Gnarly, dude.