In Amsterdam I’m staying in a B&B on a street off Van Wou Street. It’s pronounced like “von vaow”. The name amuses me. I see it as being like an intense form of wow. Imaginary conversation: “Wow.” “Better than that, man. Van Wou.”

Potato is “aardappel.” I think of the Penguins singing, “Aard Appel, Aard Appel—will you ever be mine?”

I took the train to s’Hertogenbosch (called Den Bosch for short) and spent the night. My pilgrimage to the home of Jeroen Bosch (1450-1516). The locals say his name like “Yeroon Bos.” The ride was already like being in a Bosch landscape, the Brabant landscape, with the rows of trees along the edges of the green fields. Milky sky. Willow stumps with fresh spring shoots.

I rented a bike and rode outside the town too, using a hand-winched ferry to cross a canal.

Den Bosch has a small triangular town center, with a triangular marketplace in the middle, mirroring the fact that the town originally had three gates that led to the three other main Brabant cities: Brussels, Leuven, and Antwerp. The town’s also triangular because it’s wedged into the delta where two small rivers meet: the Aar and the Dommel.

Walking around the town, I’d get these flashes that the crowds were the people of a Bosch painting. Particularly when I saw them in silhouette, and their unseemly raiment dropped from visibility.

Two Bosch houses stand on the town’s marketplace. I sat on the edge of marketplace’s old well at night, looking from one house to the other, imagining Jeroen running around as a serious boy, and walking around as a confident grown-up.

“Sint Thoenis” (for Saint Anthony) ; they lived there when our Jeroen was 12, and maybe when he was younger. It’s been burned and rebuilt a number of times, the building on the spot now houses a souvenir shop called “De Kleine Winst,” meaning “The Little Prophet.”

The second house was called “In den Salvatoer,” Bosch moved into it when he got married around age 31, it belonged to the family of his wife, Aleid van de Meervenne. It too has been destroyed and rebuilt. It now houses a shoe store called In Vivo. This house is on the north side of the market, with its windows facing south so the sun streams in.

I went into both shops of course, the owners weren’t that interested in the topic of Bosch. There exists a painting of the marketplace in Bosch’s time, with tents on it for the merchants, and this morning, by God, the market tents looked just like the picture.

I rented a room in a bare-bones hotell called the All Inn. I had a view of the spire of Sint Janskerk, which was under constrution during Bosch’s whole life.

There’s a newly opened Hieronymus Bosch Art Center in the town, housed in a deconsecrated church.

In the basement they have a little reconstruction of Bosch’s studio with a fake window like the window in the In den Salvatoer house, and a copy of that old painting of the market place on the other side of the window and—great touch—a tape of marketplace sounds playing. Church bells, geese honking, wooden cartwheels on cobblestones, pigs squealing, children shouting, cows mooing, people talking, sheep baaing, a smith hammering an anvil. Wonderful.

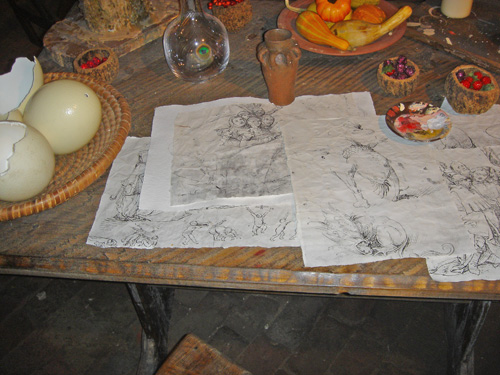

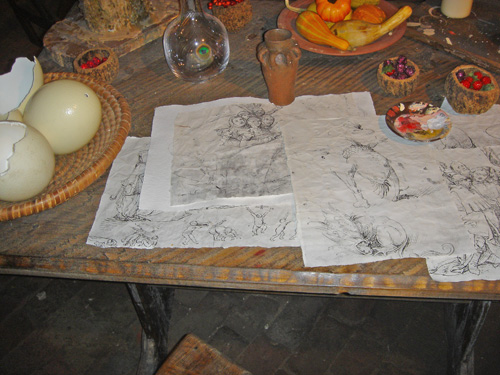

I was alone in the mock studio for half an hour, just me and—Jeroen. A nice mannequin of him stands before a canvas; he’s wearing a robe and a hat with earflaps. I sat at his work table watching him, listening to the sounds through the window, talking to him a bit, like, “Hello, Master.”

On the table were copies of some of his drawings, bowls of berries, a bowl of eggshells, a peacock feather in a glass jar, gourds. A cow skull on the wall. A stuffed heron and a stuffed owl. A lute.

Before going to the Hieronymus Bosch Art Center, I visited the building of the Swan Brotherhood or Swanbroederschap, founded 1318. They’re also called the Brotherhood of Our Lady. Bosch became a member when he was about 40, and it was a big deal. Not all that many mere painters got to join the upper-crust group. In his time a painter was just a kind of craftsman, who might take all kinds of decorating jobs.

The only way to get inside the building—which like the houses has been destroyed and rebuilt several times since Bosch’s day—was to take a guided tour in Dutch. I might have been the youngest guy on the tour! Only old people care about the past. They were Dutch, with thin lips. We looked at a small meeting room and paneled banquet room. The walls had columns with statues of swans bending their necks down to menace with their beaks. They looked a little like bagpipes.

The Dutch say swan like “zvaan.” The slogan of the society is “Sicut Lilium Inter Spinas,” like a lily among thorns, and it refers to Our Lady. There were coats of arms embroidered on the backs of the chairs—so we weren’t allowed to sit in them—these were the insignia of current members; the Swan Brotherhood is still active, initiation only, and packed with local nobles. I had the impression the people touring with me were happy to be breathing in such rarified air.

[Model of the demon from “The Haywain”]

The fireplace lintel was adorned with a sculpture of a skinny Borzoi dog with prominent ribs and little bat wings, his tail growing out long and tapering into a leafy vine. Needle-like teeth. I can see a dog taking on that appearance in my book.

I talked to one of the guides in English a bit after the tour. A big feature of the Brotherhood of Our Lady used to be their annual swan banquet; Bosch himself is known to have paid for the swan one year. I asked if they still do that, but she said no, the swan is a protected species.

Also in the Hieronymus Bosch Art Center were full-size copies of some twenty-five of the main paintings attributed to Bosch, although as Thomas Vriens told me, there could equally well be 20 or 30 instead of 25. Many of the attributions are dicey. I went through the whole collection, discussing each picture with Thomas, it was like walking through a book, wonderful. Thomas is a young art historian, working towards a Ph. D. thesis on Bosch.

I really enjoyed Thomas’s comments on “The Pedlar;” there are two versions of this painting and the man looks the same in both. He’s white-haired, intelligent, worn. It might be Bosch himself. The man is on a narrow path approaching a change; in one version it’s a little bridge, in the better version of the picture (now in Rotterdam) it’s a gate. Thomas said the gate (or bridge) stands for a transition the man is approaching: death. Not immediately, perhaps, but it’s closer than it used to be. In both he’s fending off a nasty dog with a stick; the dog is the devil, the stick is his faith.

The pedlar is looking back—on his past life, perhaps, or on the worldly things he’s avoided. In the Rotterdam Pedlar, we see an inn with pigeons flying in and out, which in medieval iconography indicates that it’s a brothel. (Beehives symbolized gluttony.) The good news is that an ox or cow stands beyond the gate the weary traveler is approaching; the ox is a symbol of Christ. The pedlar is bound for greener pastures!

I identify with the pedlar, I feel like I’m him. I’m on the narrow path, avoiding evil, and death is certainly closer than before. I fend off my enemies with my language-stick. I’m weary from life’s long journey. I’m cheered to think that when I cross that gate I’ll be safe in heaven with the Holy Cow. Mur! Maybe heaven is real.

Thomas and I also discussed the question of why Bosch had no children, and how this might have related to his feelings about sex. His wife Aleid van de Meervenne was from a well-off merchant’s family, and three years older than him, so that when they married he was 31 and she 34. I myself have sometimes wondered if Bosch disliked sex; and Thomas remarked that in his paintings one never sees real intimacy.

There’s no love or sexual passion, even in the famous “dogpile orgy” of The Garden of Earthly Delights, which is more like a cool tableau. All those toothy, red mouths in the Hell pictures suggest a fear of the vagina dentata. Yet, looked at in another way, one might say that Bosch was obsessed with sex. All those bursting seed pods speak of fertility.

And the occasionally coprophagic depictions of excretion certainly betoken a fetishistic interest in sex, which is also found, by the way, in the other great Lowlands master, Bruegel. Coming back to why Bosch had no children, Thomas remarked that health conditions were poor in those times, and it’s possible that at 34 Aleid was infertile. Also, records indicate that infant mortality was very high in Aleid’s family, so it could be that they had some children but lost them in infancy.

In those times, a man often would commission a picture, and the “donor” would then be added into the painting, often kneeling in prayer on the side with his wife. I’d heard that the donors were painted over in some of Bosch’s paintings. I’d been thinking maybe sometimes he’d finished a picture with the donor painted in, the donor had said, “That picture’s too weird, I’m not paying for it unless you change it,” and Bosch had preferred painting out the donor to altering his creative vision. Thomas didn’t see this scenario as very likely.

He said it’s more likely that when a donor died and his heirs wanted to resell the picture, in order to improve the marketability of the picture they’d get the donor painted over, if possible by the original artist himself. One possibly contentious donor-covering incident did happen.

In Bosch’s painting John the Baptist, which also contains a human-shaped mandrake root, there’s a huge mound of elaborate foliage in the middle of the picture, and infrared shows there’s a kneeling donor under the foliage. Records show that this painting was commissioned by the Swan Brotherhood of Our Dear Lady for their chapel in the Saint John’s church. The president of the society was Bosch’s neighbor, Jan van Vladeracken, and he probably got himself painted into the picture, and then the other members said, “Hey, that’s our society’s joint money you’re paying with, don’t hog the credit and have just yourself in the picture, Jan.”

[Model of a demon from “Temptation of Saint Anthony”]

Oh, one more thing about the Bosch paintings. Certainly one of his greatest works is the Lisbon Temptation of Saint Anthony. It’s a triptych showing three torments of Saint Anthony—on the left the devil lifts him high into the sky, on the right he’s besieged by lustful women, and in the middle he’s surrounded by monsters. Thomas remarked that Saint Anthony was popular in the Middle Ages of the patron saint of those afflicted by ergotism, that is, cumulative poisoning by repeated doses of a black smut or fungus called ergot which some years grew upon the rye.

As many will know, one of the compounds found in ergot is lysergic acid, a.k.a. LSD. Ergotism was accompanied by powerful hallucinations and was frequently lethal. People would blister up and their limbs would rot off. But if you survived an attack, you never forgot it. The affliction was known as Saint Anthony’s fire. They had no clue what caused it until about 1670. Ergotism may also have played a role in the Salem witch trials of 1690.

People sometimes like to propose chemical explanations for Bosch’s visions of hell. In one sense this is reductionistic—certainly I’m annoyed if someone’s only reaction to one of my weird tales is, “What were you on when you wrote that?” An artist doesn’t necessarily need to be “on” anything. In the 1960s there was a popular belief—now largely discredited—that Bosch was regularly taken psychedelic potions. That’s really not where people in his time were at. But I think it’s possible that he might have had some long, strange nights under the influence of light doses of ergot-tainted rye.

I looked at their copies of Bosch’s drawings on my own. A nice picture of an army of birds. the Peng!

Another drawing shows a dog bemusedly looking back at his butt, which has turned into a legless warty lump. As we’d say in German, “Ach du leiber, wo ist mein Arsch?” Too much ergot.

My favorite drawing is of a kind of lizard man, also with a warty, hairy gross butt. He’s posed with his butt towards you, looking back at you over his shoulder, which makes me laugh, as this is such a shop-worn “sexy” pose for women in ads, and the centerpiece of every “sizzling” Bob Fosse ballet number. “Hey there. How do you like my butt?” Thinking of the Bosch beast is way to throw cold water on that tired commercial cliché.

The next morning I went into the St. Janskerk where some of Bosch’s work had been installed. High on the ceiling above the transept is a triangle with the eye of God. Staring down, watching our every move, continually assessing whether we’re bound for Heaven or Hell.

The medieval people were really under the thumb of religion. They were endlessly obsessed with sin and punishment, and with the notion that God was always ready to judge you. A modern person might view this as a collective mental illness promulgated by the Church in order to scare people into giving them lots of money. But it’s interesting to try and get into the medieval point of view. The sensation of being watched is not, after all, so alien to modern man.