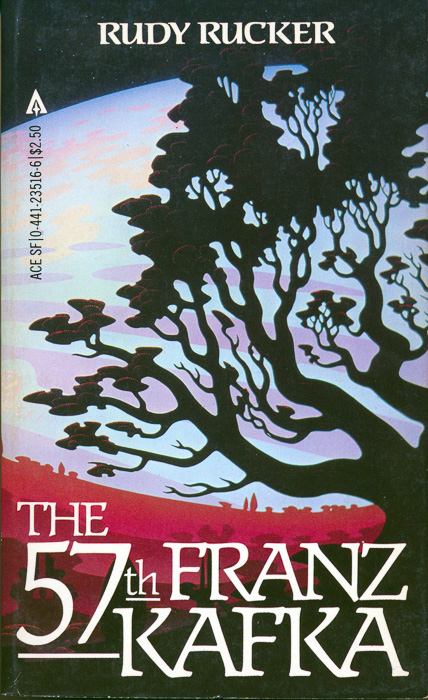

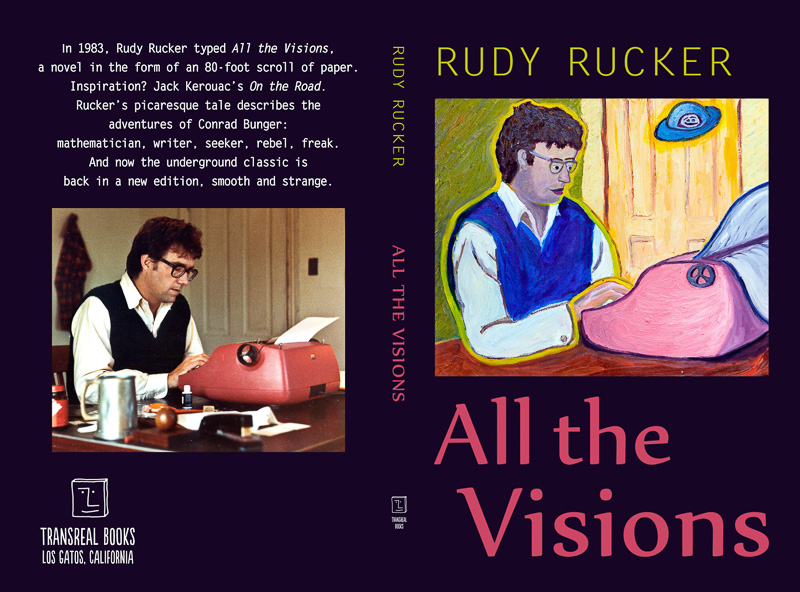

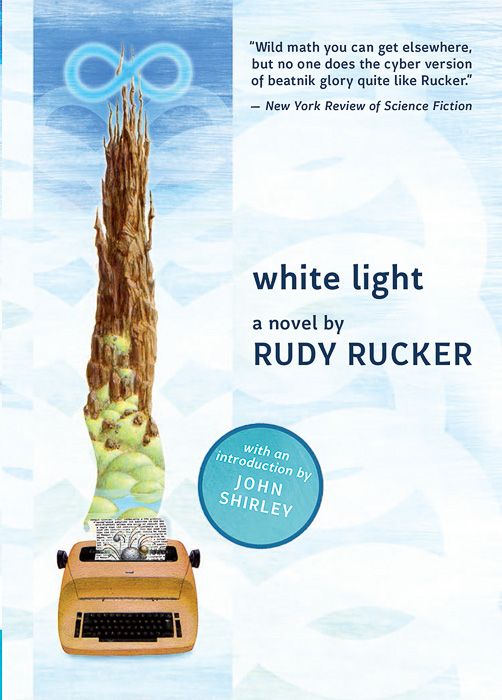

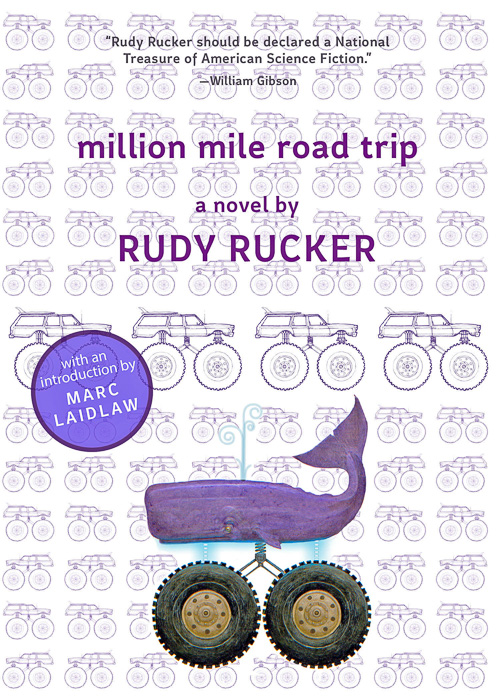

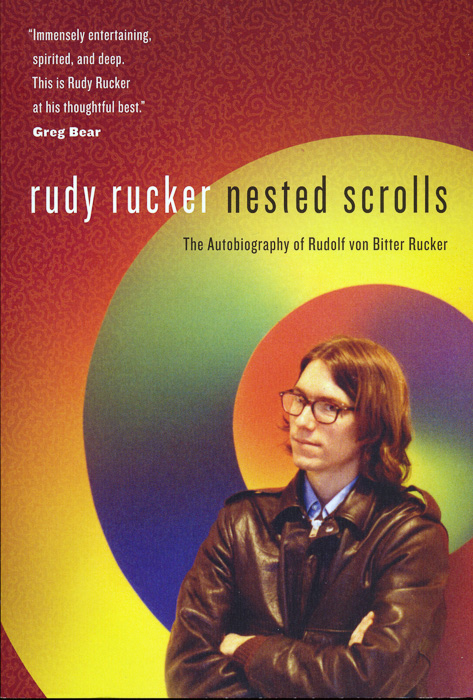

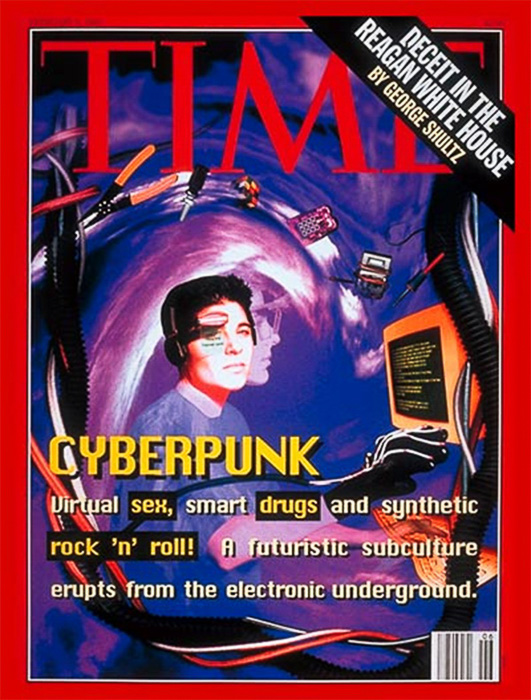

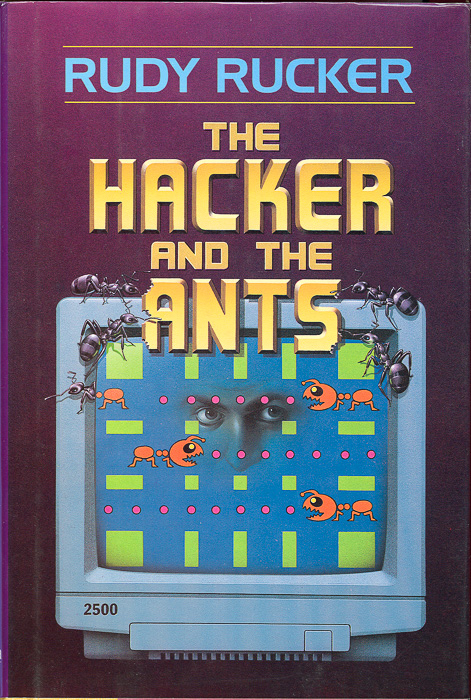

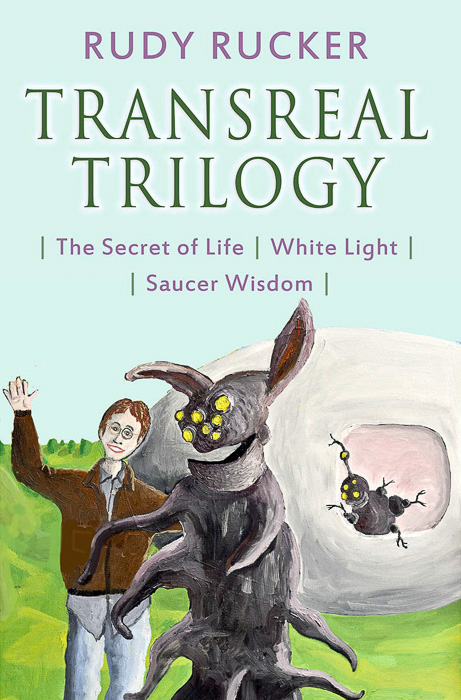

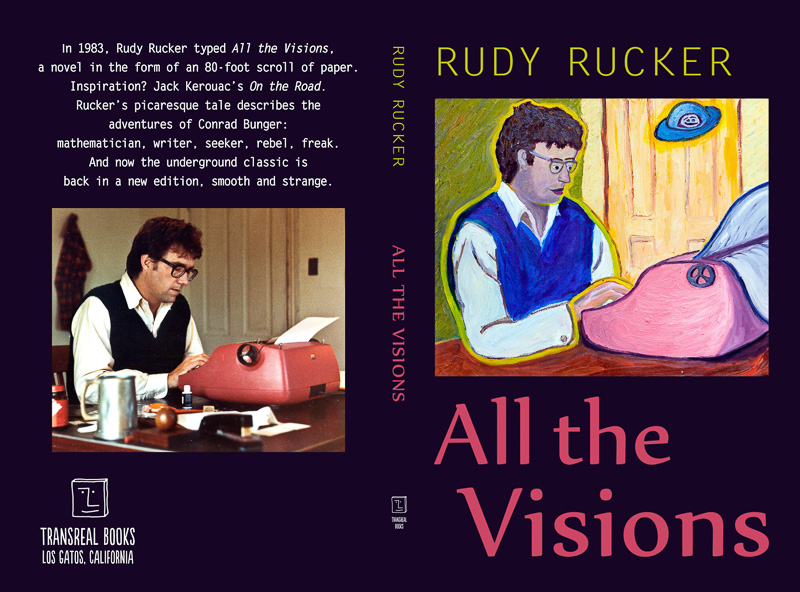

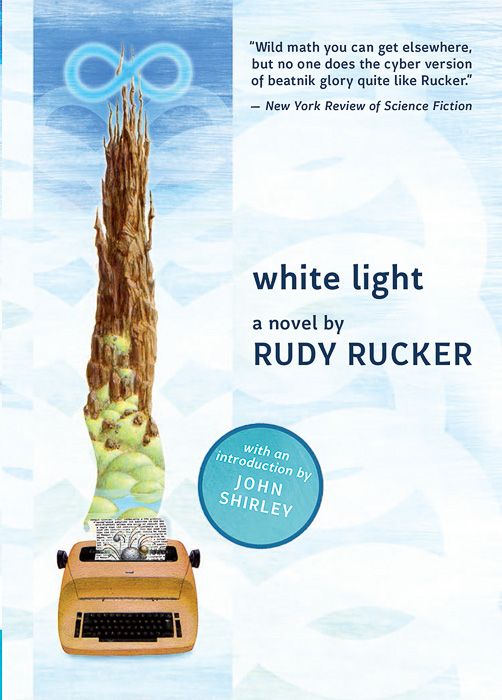

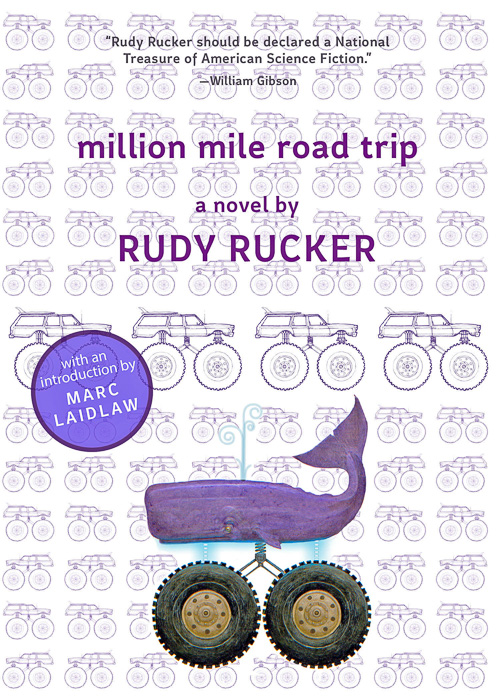

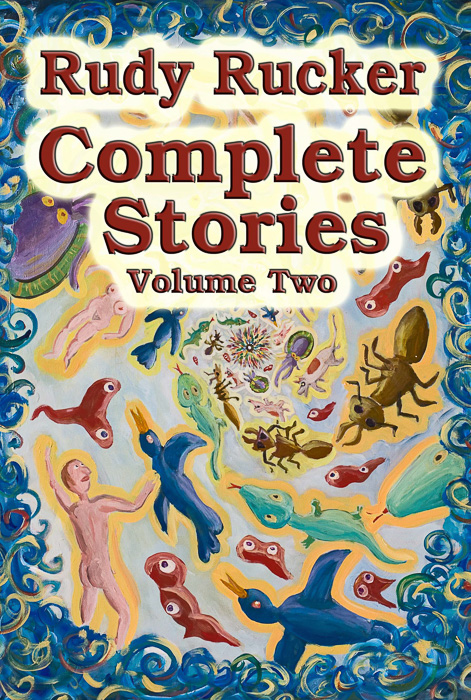

In March, Jonathan Thornton of Liverpool, England, interviewed me for The Fantasy Hive ezine. I’m reprinting most of the interview here with one change—I’ve started calling my new novel Juicy Ghosts instead of calling it Teep. For illos, I dug out a buttload of old cover images.

Q1. You’ve just finished your latest novel Juicy Ghosts. Could you tell us a bit about it?

A1. I started thinking about how digital models of people in the cloud could have more zap if they were in some way hooked into some physical living being. So they’d be “juicy ghosts.” I remember talking to Chris Brown about this after he did a reading in San Francisco, and he was, like, “That’s a great idea, and only you could pull it off.”

But I didn’t see a plot. So I spent a year or two writing stories on themes that might relate to each other and to telepathy and to juicy ghosts. And in the back of my mind I was thinking that eventually I could collage at least some of the stories into what’s called a “fix-up novel.”

In the end, I had three stories that fit together well. The first one I actually called “Juicy Ghost,” although now I’m going to call it “Treadle’s Inauguration,” as I need to keep “Juicy Ghost” for the title of the novel. And I did a story called “The Mean Carrot,” that was vaguely about the time in the ”˜60s when a CIA op was paying hookers to drug Johns with acid to see what happened. And then I wrote the longer and more humane “Mary Mary.” The first two appeared in the free underground e-zine Big Echo, in 2019 and 2020, and “Mary Mary” is in Asimov’s in March, 2021. Besides the three stories, I wrote five more story-sized chapters to produce my novel Juicy Ghosts, which I finished early in March, 2021.

Two of the main ideas I write about in Juicy Ghosts are, as I maybe said already, telepathy and digital immortality. I’ve been writing fiction about digital immortality for forty years, starting with my novel Software, which appeared in 1980. Seems like I tend to keep thinking about the same things forever. Digging deeper and deeper.

Two of the main ideas I write about in Juicy Ghosts are, as I maybe said already, telepathy and digital immortality. I’ve been writing fiction about digital immortality for forty years, starting with my novel Software, which appeared in 1980. Seems like I tend to keep thinking about the same things forever. Digging deeper and deeper.

.jpg)

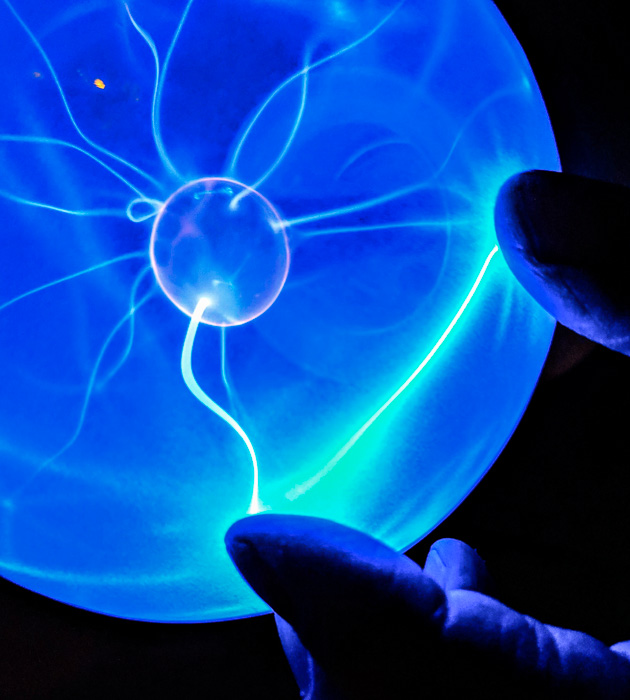

I seriously see the technology for telepathy being commercially possible in the not-too-distant future. It’s not really all that much further out than cell phones with video calls.

My take on digital immortality has to do with a thing I call a lifebox. See my nonfiction book The Lifebox, the Seashell, and the Soul. The idea, which is fairly familiar by now, is that you might be able to emulate a person if you have a really large database on what they’ve written, done, and said. And if it’s SF, then we add some AI to the lifebox so it’s an intelligent mind. Cory Doctorow also wrote quite a bit about the lifebox idea in Walkaway, and others have written about it too.

In Juicy Ghosts I delve still further into the lifebox thing. Do you have to pay to have your lifebox stored? What if the company who houses your lifebox rents it out as a gigworker? How about growing a clone to be run by your lifebox? And how do you interface a human brain with an online lifebox?

Juicy Ghosts is also quite political. I was working on the novel from 2019-2021, and all along, in my mind, I was dealing with the possibility that Donald Trump might win a second term. In Juicy Ghosts, to push it over the edge, a very similar type of President is about to be inaugurated for a third term—and, well, he gets what’s coming to him. Big time.

Not to give too much away, but my characters kill the guy three different ways—his body, his lifebox, and his clone—and then they even topple the monumental statue of him at the Top Party headquarters. I was thinking of how, in the first Terminator movie, they had to destroy the monster over and over and over. A metaphor?

To make the synchronicity weirder, my plan for the novel’s ending turned unexpectedly turned real with the Capitol riot on January 6, 2021. Fortunately in both worlds, the evil President lost. For now. So maybe you’ve got me to thank!

Who’s going to publish Juicy Ghosts? We’re sending it out.

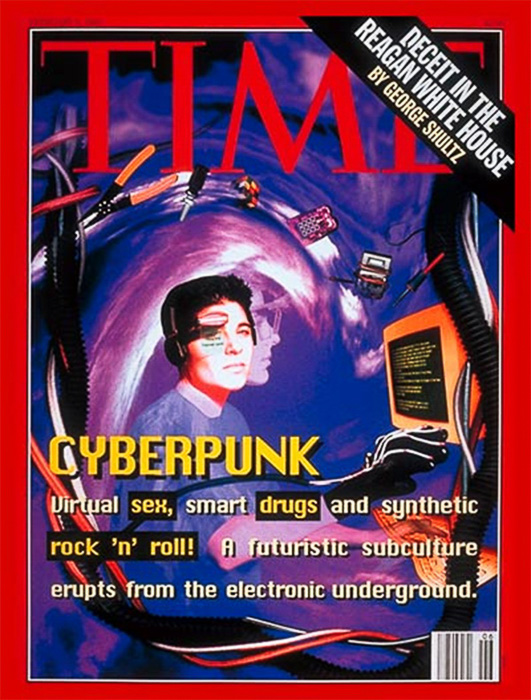

Q 2. You were part of the original cyberpunk movement, and your Ware novels are classics of the genre. On a different front, you writing transreal SF novels in which the characters mirror yourself and the people around you, and the SF goodies symbolize aspects of your characters’ psyches. How do you feel about cyberpunk and transrealism becoming popular modes of fiction in today’s world?

A 2. How do I feel? “Where are the movies of my novels? Where are my Sunday book section front page reviews? Where’s my adulation from high-brow lit- crit?”

.jpg)

I tend to be irked when I see a non-SF-literate critic being totally blown away and wonderstruck when a mainstream author pens an uninspired “speculative novel” based on some very well-known SF premise, such as a biotic robot who has a soul. The critics are, like, “Profound and wildly original. Well beyond the range of crude, subhuman SF writers.” And of course we subhumans been writing such books for forty years, and many of us dare to fancy ourselves as literary.

Wheenk, wheenk, wheenk. Wasting my breath. Bitter and old.

I’m happy to have gotten forty books published, garnered good reviews, picked up a couple of awards, and recruited loyal fans. And just this month I optioned the film and television adaptation rights for the Ware Tetralogy to a London-based production company. The deal was negotiated by Vince Gerardis and Matt Kennedy of Created By. Not the first time I’ve optioned the Wares, but maybe this time it’ll go somewhere. The guys are English! Somehow that gives me confidence.

All in all, I’ve have a great career—a lot better than I expected in my twenties. Back then I imagined I’d die in my 40s, like Edgar Allen Poe and Jack Kerouac. It helps that I got sober when I turned 50.

.jpg)

Q 3. The Ware Tetralogy novels feature a wonderful array of bizarre nonhuman life, from the boppers to the moldies to the Metamartians. Which ones did you have the most fun with?

A 3. I really liked the Happy Cloak. It’s a symbiotic or parasitic being, a bit like a coat or a scarf, and it plugs into the nerves in your neck and hangs down your back, and you get into an altered and somewhat ecstatic state of consciousness. Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore’s 1947 novel Fury introduces this notion, and William Burroughs read the novel during one of his drug-kicking treatments in a Tangier clinic.

Later Burroughs incorporated material about the Happy Cloak into in his 1962 novel, The Ticket That Exploded. As a teenager I read a lot of Burroughs. Not everyone realizes that Burroughs was, in his own way, writing science fiction. And that he’s very funny. And I read Brian Aldiss’s 1962 fascinating novel, Hothouse, where a morel fungus attaches itself to a character’s neck and begins helping him while controlling him. A bit like the Happy Cloak.

I always loved that expression Happy Cloak because of the contrast between the upbeat, childish name, and the rather sinister nature of the being. I included a Happy Cloak in my novel Software, both as an homage to Burroughs and because it was a very useful thing to have, in terms of the story. A Happy Cloak made of computational piezoplastic attaches itself to my character Sta-Hi’s neck on the Moon, and wraps itself around him as a space-suit. Happy Cloaks play a part in the later volumes on the Ware Tetralogy as well. I’m always looking for chances to talk about them.

As for the boppers, yes, they’re great. In Gravity’s Rainbow, Pynchon mentions a pinball machine painted with jiving “robobopsters,” which I liked. Maybe I got the word from that. Or from an imagined fragment about the character Cobb Anderson, “…who taught the robots how to bop.”

And the thing of having the bopper skins flow with colors was a lucky inspiration. I might have been thinking of the blinking lights on mainframe computers, or about the then-new Game of Life cellular automaton. But I wanted lots more lights, like pixels.

Later I did a lot of computer work on cellular automata, including (a) John Walker’s Cellab package for discrete-valued CAs, and (b) my own Capow package for continuous-valued CAs, which have many, many possible values in their cells. They generate gnarly, flowing patterns like lava lamps or like Belusov-Zhabotinsky scrolls.

It’s worth mentioning that the imaginary piezoplastic substance Imipolex which makes up the flickercladding or skin of the boppers is lifted from Gravity’s Rainbow as well. A lot of my career has been devoted to learning to write more and more like Pynchon did in Gravity’s Rainbow, and I think in Million Mile Road Trip and Juicy Ghosts, I’m getting close.

.jpg)

The moldies, who first appear in Wetware and come into their own in Freeware—they’re even better. Although I didn’t initially realize it, in some ways the boppers and moldies play the social role of people of color. The moldies happen to be made of flickercladding with a nervous system that’s based on fungi.

In the early 1980s, between Software and Wetware, a Texas fan who called himself Dusty Limestone mailed me a crate of brown rice with a culture of “camote” truffles growing inside it, and I foolishly ate some of them, and ended up staying up all night playing pool on the second-hand slate-bed table in our basement, and with a strong sense that I had a giant lizard tail like a T. Rex. The next day I destroyed all the rest of the camote to be sure I didn’t take it again. My friend Henry was mad I haven’t saved him any. Those were the days!

I wrote Wetware in six weeks in 1986, just before we moved away from Jerry Falwell’s Lynchburg, Virginia to—the San Francisco Bay Area. Both Software and Wetware won the Philip K. Dick award. In the late nineties, I came back to the Ware series with Freeware in 1995 and Realware in 1997. They’re largely set in Santa Cruz.

.jpg)

Concerning the Metamartians in Realware, that name amused me. They’re not Martians, man. They’re Metamartians. You didn’t want them around, but here they are! Their freeware minds arrived as cosmic rays. They come from a part of the universe with 2D time. Writing about that kind of idea is where SF can be like a thought experiment. I mean, it’s so hard to even begin to imagine 2D time, but if you try and work it into your story, then you’re forced to do the heavy lifting to get it started even a tiny little bit.

Q 4. I was fascinated by the idea of the vast “metanovel” that your character Thuy Ngyuen is working on in Postsingular. Tell me more about it.

A 4. Yeah, I had a lot of fun with the metanovel. And I really liked my character Thuy Nguyen. For about twenty years my day job was being a Computer Science professor at San Jose State University in Silicon Valley, and about half of my students were Vietnamese men and women, and I got used to seeing them and talking to them and helping them with their team projects and being friends. In Vietnam, Thuy Nguyen is a really common name. Like Jane Doe.

The Thuy Nguyen in Postsingular is a very cool woman, with a lot of attitude. If you’re a writer or a musician or an artist, and you’re good at what you do, then you know that, and you don’t necessarily care about what people think of you as a person, nor do you have to care if they like your work. You know from the inside that you’re doing it right. You’re in the groove, and with the Muse.

Thuy calls her giant metanovel Wheenk, which is kind of a joke word for me. Years and years ago I maybe have read about a rabbit being caught in a trap and making a desperate noise that was written out as, wheenk, wheenk, wheenk. Maybe it was in the SF novel Brainwave. Or maybe I saw wheenk used to represent the sound made by an agitated pig.

Anyway, I started thinking that this word is funny. And I say it or yell it at various times, like if I’m uneasy, or maybe if I’m enthused. It’s as if I have this faint, borderline touch of Tourette syndrome, in that, if a certain word or phrase enchants me, I might say it or ten or twenty times on some given day. And I’ll try to fit it into whatever I’m writing. Like a magpie tucking a shiny wire or a scrap of bright cloth into her nest. Caw!

Over time, when talking about my writing process, I began using wheenk to stand for a character’s repetitious inner thought loops. Like: “Will I ever find love?” “Will I get a job?” “Does everyone hate me?” And when a character is thinking that, they’re bascially going wheenk, wheenk, wheenk.

It’s very common for a bestselling novel to have lots of scenes where the hero or heroine is repeating some worry to themselves. And it can get boring, at least to me. By way of dissing a book like that, I say it has too much wheenk.

At the other pole, I myself have to beware of writing a thrilling superscience adventure so rife with gimmickry, incidents, and jest that my characters never pause to reflect on what’s happening to them, nor to ponder where they’re trying to go. In this case, I say my draft needs more wheenk. And I try to work some in.

I remember discussing this with my younger friend Richard Kadrey some years ago, when he was still starting out, writing the first of his hugely successful urban fantasy novels, and I was telling him that it’s good to include a romance plot as well as action.

“You need the wheenk,” I told him. “Do you have wheenk in the book?”

Richard paused, thinking it over. “Well, okay, I have my guy out in an alley behind a bar, and he’s just killed a demon, and then, in his head, he wonders how this woman he likes is doing.”

“That’s a start,” I said. “But more wheenk.”

Which brings us, via a commodious vicus of recirculation, back to Thuy Nguyen’s metanovel Wheenk. Here’s two bits of description lifted from Postsingular.

“Thuy was working on her own metanovel, an as-yet-untitled combine of words, links, video clips, images and sounds—she meant for it be a bit like a movie that a user could inhabit, the user coming to feel from the inside how it was to be Thuy, or, rather, how it was to be a version of Thuy leading a more tightly plotted and suspenseful life.”

“Thuy was making Wheenk into what she termed a transreal lifebox, meaning that her metanovel was to capture the waking dream of her life as she experienced it—while sufficiently bending the truth to allow for a fortuitously emerging dramatic plot. Thuy wanted Wheenk to incorporate not only the interesting things she saw and heard, but also the things that she thought and felt. Rather than coding her inner life into words and real-world images alone, Thuy was including beezie-built graphic constructs and—this was a special arrow in her quiver—music. The goal was that accessing Thuy’s work should feel like being Thuy herself.”

Welcome to my world.

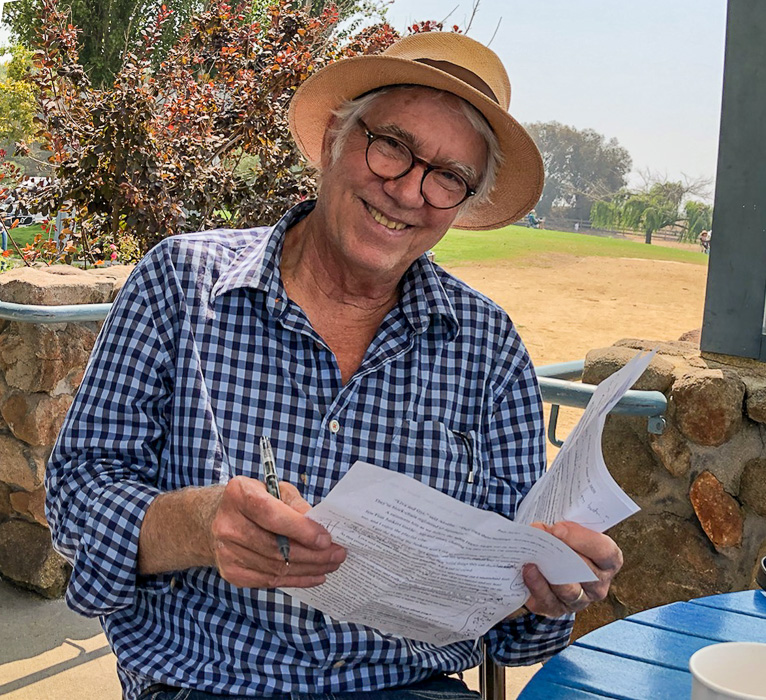

Q 5. What’s next for Rudy Rucker?

A 5. Whenever I complete a novel—and I just finished writing Juicy Ghosts—after a long haul like that, I say enough’s enough, I’m too old and tired, don’t make me cross the Pacific Ocean in a rowboat again. But then some months go by, or even a couple of years, and I start missing having a novel to live in.

.jpg)

When I’m busy with a novel, I’m inside it a lot of the time. Thinking about the scenes and the characters. Sitting down to work on it nearly every day. The characters become my friends, and they make me laugh, or mist up, or worry. And it’s nice to have this illusion of an emotive social life.

The granular craft of writing is something I relish more and more—the matter of choosing the right word, having a tasty rhythm in the phrases, and knowing how to swerve—so as to keep the reader alert and off balance.

I love the subtle, indescribable way that the scenes and the dialog come to me. I don’t exactly get there by trying, as all followers of Yoda know. But I do have to keep showing up. And while I’m waiting for the Muse, I work on my writing journal, with notes about possible ideas or what I’m doing or how I feel. And when the Muse kicks in, I stop thinking and I do. The process turns subconscious. I’m just typing it out, chuckling and rocking—a grinning idiot. And as the novel goes on, I dive deeper and deeper. It’s paradise.

Before I can start a novel or a story at all, I need to have a place that I want to go. When I was younger, there was that default space-opera future that SF was supposed to be about. And cyberpunk was about breaking out of that. I never had any interest in being a hereditary aristocrat in the Space Navy! Misfits doing crazy things, that’s what I like. Mad scientists.

What might I do next? Maybe space travel as long as we don’t use a boring metal spaceship or, please no, not a generation starship. In Million Mile Road Trip I had them travel across the galaxy in a car. In Frek and the Elixir I had them do huge hops in a living UFO. And of course Robert Sheckley’s characters had space hoppers in their driveway, or they bought one at something like a used car lot—maybe I could go back and do that. Sheckley is forever the great hero of my youth.

Biotech has endless possibilities, and I touched on some of them in Saucer Wisdom (which is a “novel” in the same way that Nabokov’s Pale Fire is a novel), and in Postsingular, and again in Juicy Ghosts. I’m also fascinated by the notion of ubiquitous physical computation, and the “hylozoic” notion that things might be conscious and alive. I ran with that in Hylozoic.

I’ve always liked the 1940s or 1950s stuff, with the mad scientist in his or her garage. Gyro Gearloose! It would be fun to write about that totally new thing that a lone mad scientist might discover in the next thirty years, a fun idea like a new wind-up toy I can put through its paces.

.jpg)

The science news is eternally a holiday parade that doesn’t end. Grab hold of anything you see. Tweak it a little bit, and make it your own. Connect it in some way to your actual personal life—that’s the transreal move. And go a little meta—that’s a tricky tactic I’m forever trying to master—flip your idea up a level and into something having to do with states of consciousness, or with the nature of language, or with the meaning of dreams.

There’s still so much. We’re just getting started. We’re doing it wrong. We’re getting better.

![]()

![]()

Two of the main ideas I write about in Juicy Ghosts are, as I maybe said already, telepathy and digital immortality. I’ve been writing fiction about digital immortality for forty years, starting with my novel

Two of the main ideas I write about in Juicy Ghosts are, as I maybe said already, telepathy and digital immortality. I’ve been writing fiction about digital immortality for forty years, starting with my novel .jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)