More from my memoir-in-progress, Nested Scrolls.

One of the last things I did in Lynchburg, Virginia, in 1986 was to join in a riverboat regatta. In 1775, two of my local ancestors, Anthony and Benjamin Rucker, had designed a flat-bottomed wooden boat that could be poled down the James River from Lynchburg to Richmond. They used it to ship hogsheads of tobacco from the local farms to Richmond. In numerous spots, the river becomes shallow rapids, so you have to slide your boat over the stretches of rocks—thus the sturdy, flat bottom. The Ruckers’ boats were called bateaus, and, with the help of their friend Thomas Jefferson, they patented the design.

In 1986, some people in Lynchburg had the idea of getting a bunch of crews to build their own bateaus, and to have a five day boat race down the river from Lynchburg to Richmond. (Since then, this has become an annual event.) My friend Henry Vaughan and I joined the rotating crew of the Spirit of Lynchburg for one day—camping out the night before in a pasture by the river.

It was nice out on the James. Henry and I wore kerchiefs against the sun, and I started calling him Otha, after a black guy named Otha Rucker whom I’d met in traffic school. The only hassle was that our so-called captain was a gung-ho jock who was seeing this event as a serious athletic competition, and kept exhorting us to pole like crazy, push through the wall of pain, put out a hundred and ten percent, bullsh*t like that.

Our home-made boat was so heavy and leaky that after the first hour, we were in last place, with the other boats out of sight far ahead. Maybe the preppy jock thought he was the captain—but, being a Rucker, I figured I was the Shadow Captain. I mocked and chaffed the tyrant, evoking merriment from the crew. At the end of the day, the jock wanted to slug me, but I slipped out of his reach amid my fellows.

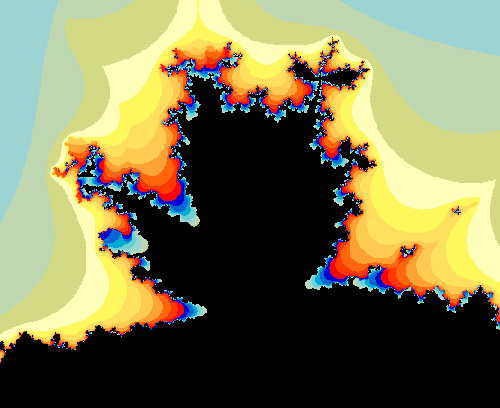

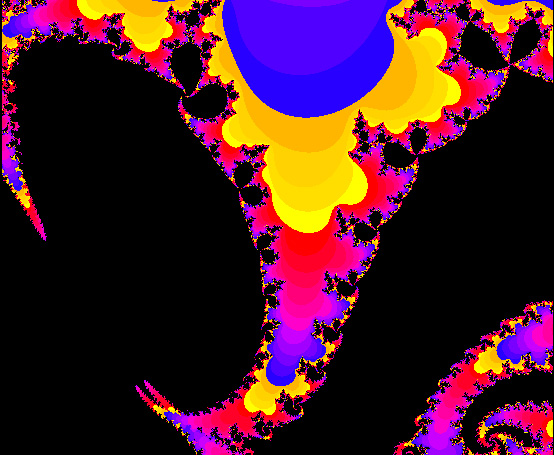

Back in my Lynchburg office, three young artists from Richmond come to see me, as if sent by Eddie Poe to meet the Shadow Captain. They’d brought me some beautiful drawings of tesseracts unfolding, and of four-dimensional cubes. It was exhilarating to learn that, bit by bit, my ideas were getting out there.

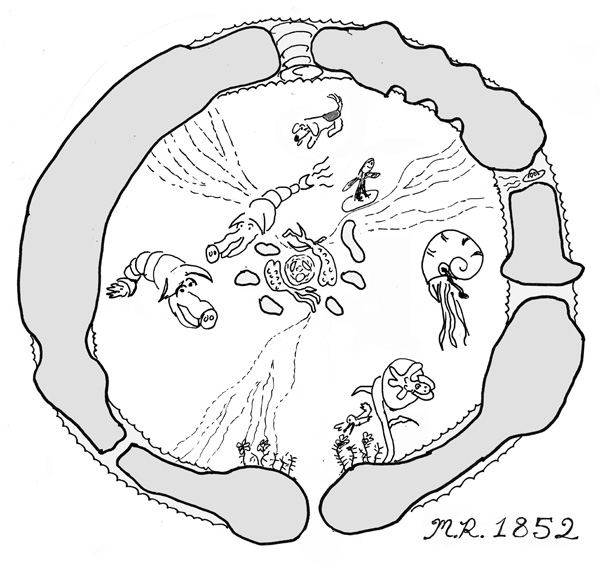

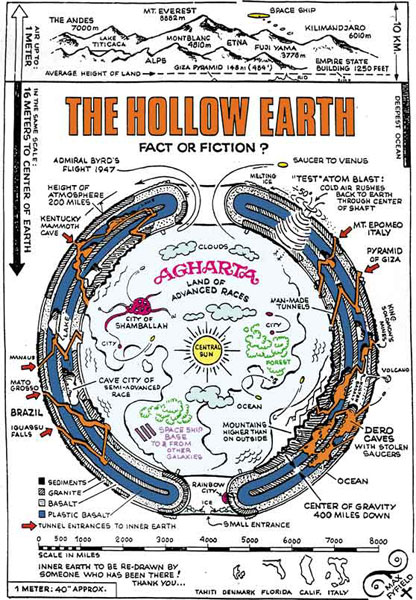

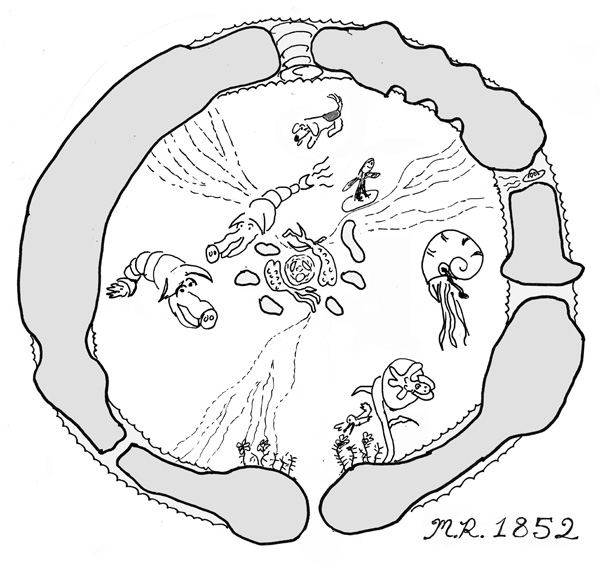

[Drawing for the 2nd Edition of the Hollow Earth, see explanation.]

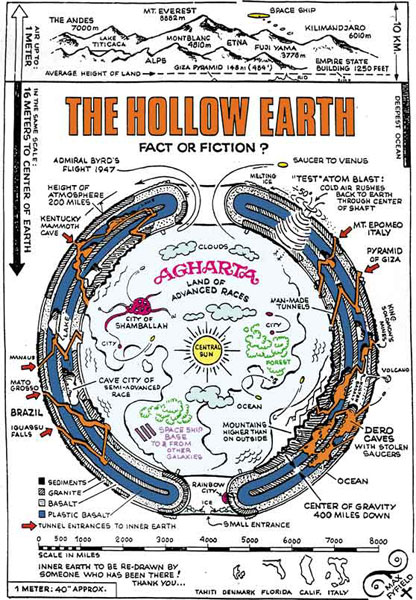

I began thinking about writing a historical SF novel involving one of my favorite notions from fringe science: the Hollow Earth. The idea is that our planet is in fact hollow like a tennis ball or like a fisherman’s float. A race of people live inside. But how do we get in there? Perhaps through holes in the ocean floor, or perhaps via an immense hole at the south pole.

My special inspiration was Edgar Allen Poe’s novel, The Journey of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, which describes a sea voyage to the walls of ice around the Southern pole, with the implication that there is a huge opening to be found there, a great shaft leading into Mother Earth’s womb. Wanting this to be true, I reasoned that, even if Poe had erred about the hole being clearly visible, it might well be hidden beneath a sheet of accumulated snow and ice.

[See my paintings page for more info about my artwork.]

My old friend Gregory Gibson, in his capacity as antiquarian bookseller, sent me Wilkses’s The Narrative of the U. S. Exploring Expedition 1838-1842, Benjamin Morrell’s, A Narrative of Four Voyages to the South and North Seas, plus a fine twenty-volume edition of the collected works of Poe, who in fact used Morrell’s book himself.

I pored over these volumes, coming to identify with Eddie. He wrote of being possessed by an imp of the perverse, who impelled him to do deliberately alienating and antisocial things—which described my punk attitude to a tee.

While in Lynchburg, my expanding researches led me to the rare book room in the library of the University of Virginia, where I found writings about John Cleves Symmes, Jr., who began proselytizing his doctrine of the Hollow Earth in 1818.

Symmes lived in Newport, Kentucky, and he styled himself the Newton of the West. He was too busy lecturing—or too sly—to publish any books under his own name, but I found a nonfiction Symmes’ Theory of Concentric Spheres, and a novel, Symzonia: A Voyage of Discovery, which are purportedly written by Symmes’ followers. My feeling is that, as the books speak so very highly of Symmes, he either wrote them himself or collaborated heavily.

[A classic drawing of the Hollow Earth, see this post for further H.E. info.]

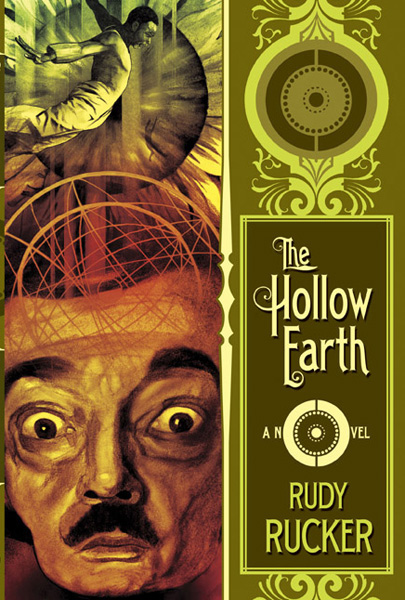

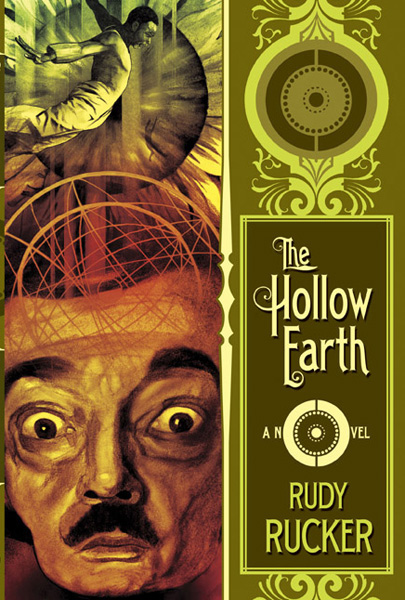

In California, I started work on my novel, The Hollow Earth: The Narrative of Mason Algiers Reynolds of Virginia. The book eventually appeared in hardback and in two paperback editions, and in ebook. There’s even a free “Creative Commons” ebook version online.

The novel is about a country boy who leaves his farm, travels down the James as a stowaway in a bateau, accompanied by his dog Arf and his childhood companion Otha, who’s now an escaped slave. They meet Edgar Allan Poe in Richmond, and they travel onward to Antarctica and to the Hollow Earth.

I wasn’t sure how to light up the inside of the Hollow Earth, a land which I called Htrae. If you put an Inner Sun in the center, then it seems like everything would fall up into the sun. One day when I was walking around San Francisco with Marc Laidlaw, I found the solution.

It was a new science toy called a plasma sphere, on display in a New Age shop. By now nearly everyone’s seen these one of these things—it’s a hollow glass ball with an electrode in the center. Branching lines of electrical discharge reach out from the electrode to the outer surface, and if you move your fingertips around on the sphere, the glow lines trail after them. That’s the way to light up the Hollow Earth! Have great aurora-like streamers of light reaching from the Central Anomaly to the inhabited inner surface of Htrae.

The writing went slowly. I find it hard to keep my novelistic momentum if I only have a spare hour here and there in which to write. The only extended patches of free time that I had were during the school vacations—especially in the summer—but often we’d want to take family trips then, taking road trips around California or flying to visit Sylvia’s father and brother in Geneva.

When my first August in California came to an end and the fall semester loomed, I thought of the early sailing ships trying to reach the fabled southern continent of Antarctica. Sometimes they’d overstay the brief polar summer, become iced in, and spend the dark, howling winter hunkered in their vessels, hunting seals for food.

[Go to my “Hollow Earth” page to see the paperback and ebook editions available .]

Repeatedly iced in by my teaching duties as I was, it took about three years to finish writing The Hollow Earth. When I was done, I used the hoaxing Poe-like expedient of pretending that The Hollow Earth was a manuscript that I’d found in that rare books room at the University of Virginia.

To this day, I get occasional emails from readers taken in by this. They wonder why I haven’t done anything to help mount an expedition to retrace Mason’s steps. One guy even assumed that since The Hollow Earth was just an old public-domain manuscript that I’d edited, it was okay to post a page-scan of my book on the web!

[Kids with Arf, canine hero of The Hollow Earth.]

My kids liked hearing me talk about the Hollow Earth. Once when we were on a cross-country skiing vacation at Lake Tahoe, I pointed out to Isabel the blueness of the light that seemed to emerge from the holes our ski-poled made in the snow.

“Proof that the Earth is hollow!” I told her.

“As if more proof were needed,” she responded cheerfully. “When will they see?”

Oh, one more thing. There was an article about my novel in the paper in San Jose, and a bum came by my office to tell me this news:

“The sun is cold and hollow. That light you see overhead is just the interaction of some special rays from the sun with our upper atmosphere. I used to be a very famous surfer, you know. Look.”

He pulled out a page torn from an encyclopedia with a grainy picture of someone on a wave.

“That’s me. Inside the Hollow Sun.”