Yesterday I was out a favorite spot on Four Mile Beach, north of Santa Cruz. That forest fire they had inland has pretty much died down. I did a little routine that I’ve often done while working on a new novel in recent years—I draw a logarthmic spiral in the sand and I letter the slogan, “EADEM MUTATA RESURGO”, which is Latin for “The Same, Yet Changed, I Re-arise.”

The mathematician Jakob (also called James) Bernoulli (1655-1705) has this inscribed at the very bottom of his tombstone in Basel along with a picture of a spiral (the engraver mistakenly depicted a regular Archimediean spiral instead of a wildly growing logarithmic spiral, like the kind you see on seashells).

I started this particular routine while writing Frek and the Elixir, and in fact the slogan is mentioned in that novel. If you feel like it, you can search my blog for “resurgo” to see the other spots where I’ve mentioned it.

I did some good work on my novel-in-progress Jim and the Flims today. Here’s a fun passage I wrote today, about a sinister alien plant. [Note that what I’m printing here is only the first draft, and I will in fact be revising it repeatedly on my way to finishing the novel.]

In the morning, Durkle woke me with a nudge of his foot. I heard a babble of voices nearby. Sitting up and looking around, I saw something like an umbrella projecting from the ground a short way off.

“It’s an offer fan,” said Durkle. “Did I tell you about them? A mobile plant—see those writhing roots at its base? They can walk, a little bit. It must have teeped us here. Mostly they live in the swamp, a few miles off. Isn’t it cool? I’ve heard you can get anything you want from an offer fan—if you’re quick enough. Watch me.”

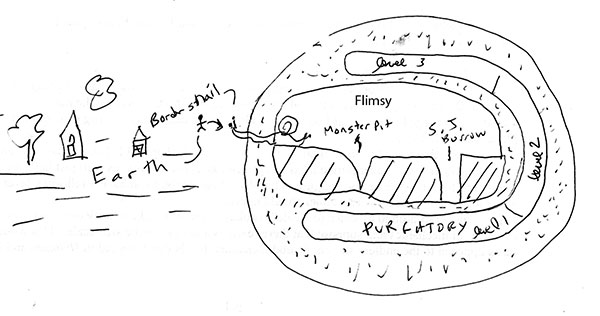

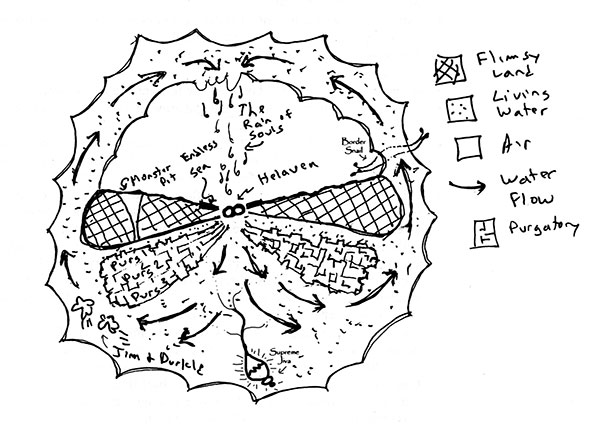

All sorts of desirable objects were dancing beneath the offer fan’s greenish umbrella. It seemed that the offer fan could read my mind, for as I stared, it produced some items that I myself might want right about now: a cup of tea, fried eggs on rye, a map of Flimsy, a bag of pot with rolling papers, and a cantaloupe—all marching in giddy circles with the others across the roots beneath the thick umbrella, everything seemingly quite real. Perhaps the odd, alien plant had perfected a kind of direct matter control?

It was of course obvious to me that I shouldn’t try grabbing for the goodies, but Durkle was a willing fish for the bait. Having grown up in a land without computers or television, the boy was naive. Manfully he approached the offer fan, skipping to the left and the right as if he hoped to outmaneuver it.

The fan’s umbrella made continual slight adjustments in its position—the broad cap sat alertly atop a flexible stalk the thickness of a leg. I noticed that the underside of the umbrella was spongy and damp, as on certain unwholesome mushrooms. The thing’s roots were twitching and obviously eager to act. I was guessing that the fan’s kill technique would involve poison spray as well as strangling.

Durkle seemed oblivious of the risk—his eyes were fixed upon a scuffed-up board identical to Flam’s, a tasseled orange racing cap, a little chessboard, a shiny sword, and a fleshy glob that was forming itself into the body of—a naked woman, but with rounded off arms and legs and a smooth bulb for a head.

“Stop right there, Durkle!” cried Ginnie, sitting up beside me.

“I know I can beat this thing,” said Durkle, glancing back at her. “You want me to get you something too, Ginnie? Make her something, fan! I dare you.”

Sensitive to our group’s dynamics, the fan extended its offers to include a steaming mug of coffee and a very fashionable pair of sunglasses in wide tortoise-shell frames. Durkle crouched, preparing for his final dash.

I couldn’t let this continue. I ran forward and grabbed him around the waist.

“Senile loser!” he hollered. “You’re just jealous that I’m young and fast! Ginnie wants me, not you!”

Maybe I was old, but I had a jiva inside me. Durkle wasn’t going to break free of my grip. But he did manage to knock me off balance. The two of us fell to the practically into the shadow of the offer fan’s umbrella—a very bad place to be.

Fast as a whip, the thing had its roots around our wrists and ankles. And now, sure enough, an evil-smelling mist began wafting down from the cap. Most of the offers had disappeared now that the fan was getting down its real business. It’s central stalk tilted over, maneuvering the umbrella so that it could flop down right on top of us. I felt drowsy, and the spray was stinging my skin. As well as being a soporific, the spray was a digestive fluid.

Suddenly the umbrella tumbled off to one side. Ginnie’s jiva had cut the stalk! The offer fan let out a telepathic scream that filled my mind with red and yellow jaggies. Ginnie was circling around us, lashing at the carnivorous plant with her jiva tendrils and now—slow as always to defend me—my own jiva, Mijjy, began attacking the offer plant as well.

Durkle had managed to free one of his wrists and he’d gotten hold of that little sword the plant had made as bait—this desirable item had remained on offer to the end. It was indeed a real and solid blade. The boy slashed away at the roots, freeing our hands and ankles. He crawled a few feet away and tugged me after him. Slowly the fan’s frenzied alarm waves within my head died down—and the mist drifted away. I could think again. In a belated coup de grace, Mijjy set the remains of the offer fan on fire.

“Got any more good deals for us?” I asked Durkle.