This week I’ve been working on the final revisions of Nested Scrolls: A Memoir, my autobiography. I’ve contracted for it to come out in a collector’s edition from PS Publishing in England, and then in a trade edition from Tor/Forge Books in the US. I’m not sure about the publication dates yet, either 2011 or 2012.

Today I’m running an excerpt from some material that I just added, a passage about blogging and photography. The photos are mostly from a recent walk on St. Joseph’s hill near Los Gatos.

After five and a half years of blogging, I’ve put up some seven hundred posts which, taken as a whole, bulked to a word count comparable to that of three medium-sized novels.

Have I been wasting my time? What’s the point of a blog?

The issue of wasting time is a straw man. A big part of being a writer is finding harmless things to do when you aren’t writing. To finish a novel in a year, I only have to average a page a day, and writing any given page can take less than an hour. So I do in fact have quite a bit of extra time. Of course a lot of that time goes into getting my head into the right place for the day’s writing—and then contemplating and revising what I wrote. But blogging isn’t a bad thing to do while hanging around waiting for the muse.

[Marble rye sandwich with avocado smears.]

I often post thoughts and links that relate to whatever writing project I’m currently working on. And my readers post comments and further links which can be useful. So to some extent my blog acts as a research tool.

Another thing about a blog is that it serves as a tool for self-promotion. By now, my blog has picked up a certain following, and every month it receives about a hundred thousand visits. The only ads I run are for my own books.

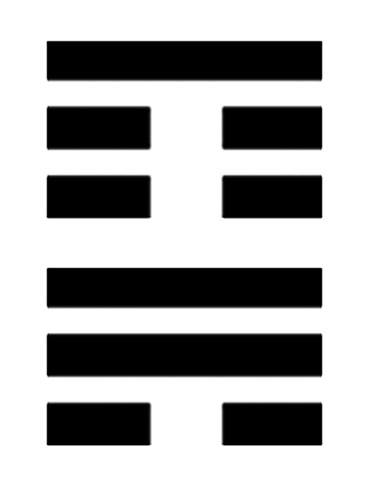

But my blog isn’t really about research or commerce. The main reason I keep doing it is that the form provides a creative outlet. I like editing and tweaking my posts, and I like illustrating them. I alternate text and pictures, usually putting a photo between every few paragraphs.

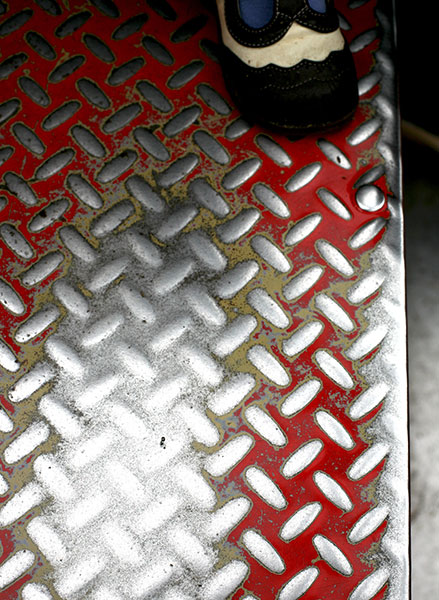

I need to mention that I switched over to digital photography around the time when I started my blog in 2004. I’ve used a series of pocket-sized SONY Cybershot models, a heavy-duty Canon 5D single-lens reflex camera, and a medium-sized Canon G10.

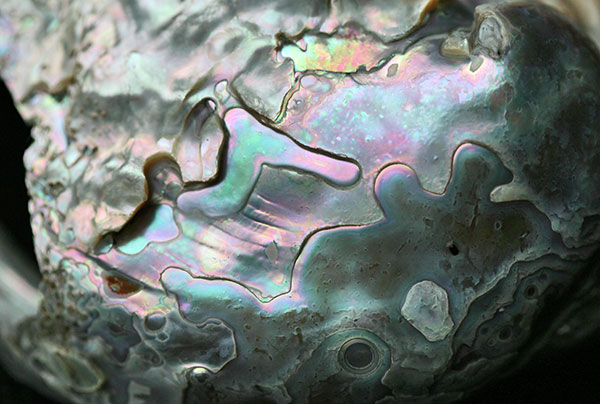

I carry a camera a lot of the time, and I’m often on the lookout for photographs. I sometimes think of photography as instant transrealism. When it goes well, I’m appropriating something from my immediate surroundings and turning it into a loaded, fantastic image.

When incorporating my photos into my blog, I don’t worry much about whether the images have any obvious relevance to the texts that I pair them with. My feeling is that the human mind is capable of seeing any random set of things as going well together. So any picture can go into any post. It’s like the Surrealist practice of juxtaposition, or like the old Sixties game of putting on music while you watch a TV show with the sound off. Our perceptual system is all about perceiving patterns—even if they’re not there.

This said, if I have enough images on hand, I will do what I can to bring out harmonies and contrasts among the words and the pictures. Subconscious and subtextual links come into play. Assembling each blog post becomes a work of craftsmanship. It gives me a little hit of what the John Malkovich character in Art School Confidential calls “the narcotic moment of creative bliss.”

Having the blog and the digital cameras has revitalized my practice of photography. With the blog as my outlet, I know that my photos will be seen and appreciated. It’s not like I’m just throwing endless packs of photo prints into a drawer. For many years, Sylvia assembled our photos into yearly family albums, but now, with the children gone, she’s let this drop. “The kids don’t want to see albums of us two taking trips,” she points out. And I’ve gone online.

Digital cameras are a whole new game for me, after using film cameras for forty years. I like how my digital cameras give me immediate feedback—I don’t have to wait for a week or a month to learn if my pictures were in focus. And I like using my image-editing software. I crop my pictures, tweak the contrast, mute or intensify the colors, and so on. It’s like being back in the darkroom with, wonderfully, an “Undo” control.

And now that I have my photo-illustrated blog, my camera acts as even more of a companion to me than before. When I’m out on the street, I’ll sometimes slip into a photojournalist mode of searching out apt images while making mental or written notes for a post.

An interesting effect of the internet is that, if you’re a heavy user, your consciousness and sense of self become more distributed and less localized. Even when I don’t have the camera along, the blog is a kind of companion, a virtual presence at my side. My old sense of self used to include my home, my workplace and the coffee shops I frequent—but now it includes my blog and my email. Bill Gibson was right. Cyberspace has become a part of daily life.