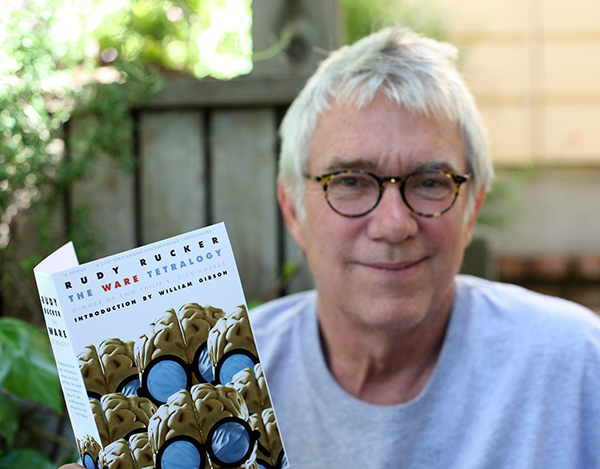

I finished the proofing on The Ware Tetralogy, and got a preprint of the cover.

The four Ware novels had been scanned from the old paperbacks by bookz-pirates, and I had to correct a number of typos that had crept in. Being a writer, I can’t reread something of mine without seeing things to fix, so I made a few small tweaks as well—making the novels consistent from one to the next, and smoothing the flow.

It looks good, and should be out in June. Go ahead and pre-order a copy now! It was interesting for me to go over those old books again—some of it has this great wild and mad energy of a young writer.

Oh, and I should mention that my most recent novel Hylozoic is out in paperback and all e-book formats now.

My friend Leon Marvell just sent me a tape of a talk I gave at the University of Melbourne on November 24, 2009. The topic is, “My Life as a Writer.” It’s about forty minutes long, with ten minutes of Q&A. I put it up as a podcast; click on the icon below to access the podcast via Rudy Rucker Podcasts.

I’m working on a couple or three stories these days, hoping to do some of them as collaborations with other SF writers. I’m also working on a big painting inspired by Terry Bisson’s amazing anthology, Billy’s Book. Terry is some kind of master.

I just finished reading Cory Doctorow’s cool new novel Makers which, by Cory’s usual policy, you can also download for free at his site. It’s an epic-length story about two guys using 3D printers to make smart knick-knacks and ghost-house-type amusement park rides.

An unusual thing about the book is how much of it is about standard and alternate ways of organizing large businesses, with many conversations about law suits and legal stratagems. A more typical SF writer would run with the self-reproduction aspect of 3D printers, push on into biotech “printers,” or expand upon Cory’s exploration of what kinds of gadgeteering the ubiquitous 3D printers might bring about. But, perhaps because of his time working with the Electronic Freedom Foundation, and because of his years-long agit-prop against commercial ebooks with digital-rights-management systems, Cory loves spinning out variations on scenarios involving intellectual property rights.

I enjoyed the book’s manic, off-kilter pace. I liked the tinkering, and I rooted for the characters. But, as an aside, I have to say that I no longer feel a great enthusiasm for Cory’s ideas about giving away one’s personal intellectual property. I raise this point because one of his characters, Perry, is very committed to such principles, to the point of walking away from seemingly good deals.

But I do like the way the Cory’s essays and novels are opening up the range of possibilities that we can easily envision. And I love the whole do-it-yourself ethos. My own impossible dream on this front is that we might find a way to realize a simulacrum of Ted Nelson’s notion of having there be in some sense only one electronic copy of, say, a novel. And everyone would be reading that one copy, and we could easily charge admission, like the owner of a living, breathing two-headed calf in a sideshow tent. And you could keep the tent right in your own back yard.

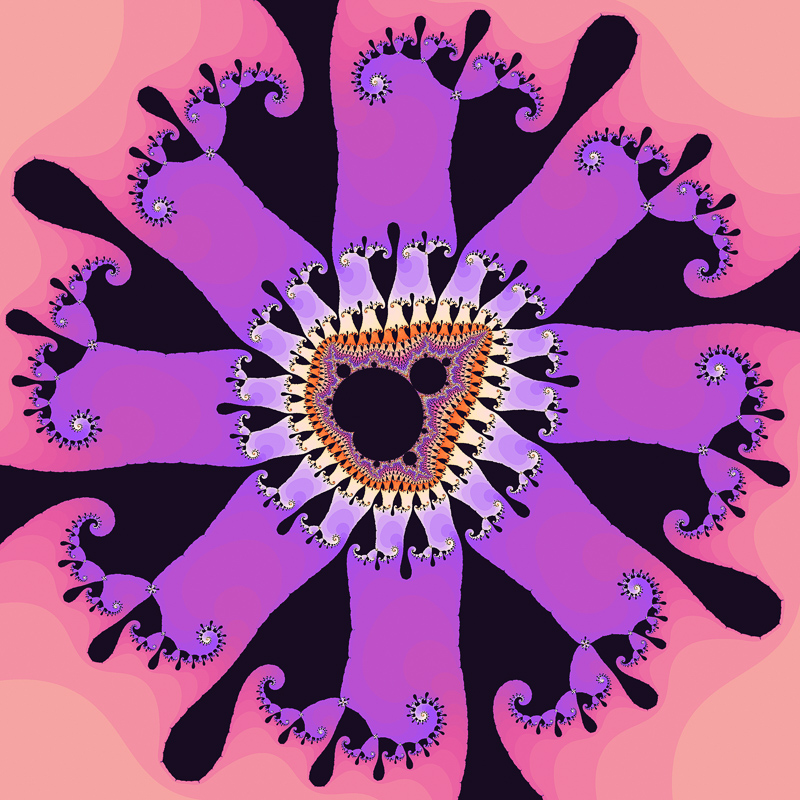

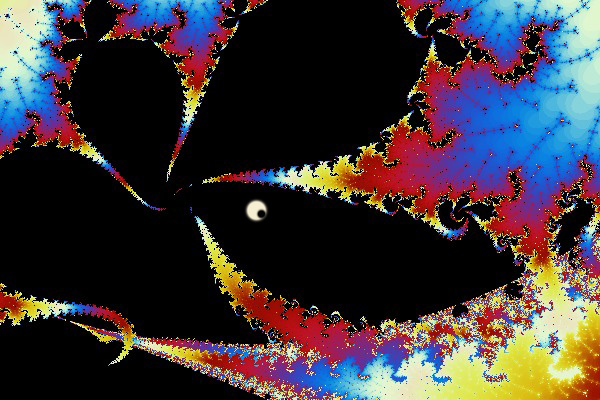

[Mickey Rat, the anti-Disney icon, was spotted today inside the quadratic Rudy set fractal!]

[Going off on a tangent for a moment…on the writing front, looking ahead ten or twenty years, it seems possible that a writer’s main market outlet (especially for back-list books) will be electronic books of some kind. Not that this is a sure thing. Maybe paper really will have the lion’s share forever. But at this point, the the notion of giving away your electronic books free is starting to seem illogical for a writer who wants to make a few bucks off his or her work in the future. Yes, if you’re personable enough, you may be able play off your renown to get paying gigs as a speaker or a consultant. But many of us don’t want to go out and consult or make appearances. That’s a whole other job. For some of us, going on the road and meeting people is too much work. We’d like to stay home and write, with the expectation that a steady trickle of money will flow in for as long as people read our writing and take the road of buying non-pirated electronic editions. Like with music. And, yes, I’m conflicted and confused about this. We writers do love to be read, even if we have to give our stuff away.]

Back to Makers . It’s striking how much of the novel is about Disney and about amusement park rides. I’d kind of thought Cory got this out of his system with Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom. But he has this really deep obsession with Disney—when I saw him at WorldCon in LA a couple of years ago, he mentioned that, while living in LA, he’d gone to Anaheim Disneyland and it’s associated venues an exceedingly large number of times. Although he resents the authoritarian, closed-standards aspects of the corporation, he does love the rides and the alternate realities.

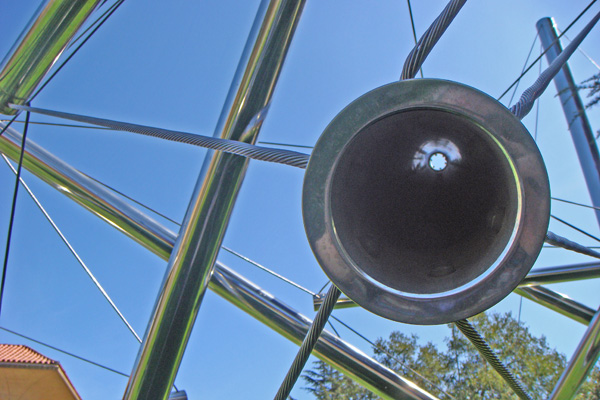

When a writer returns to a certain theme over and over again, it’s tempting to try and find a deeper, subtextual meaning for the theme. I myself was obsessed with amusement park rides as a boy—for me it was all about the midway at the annual Kentucky State Fair in Louisville. And I still love going to the Boardwalk in Santa Cruz. I do remember being pleasantly surprised when I finally made it to a Disney park when I was about thirty, I was thinking, “This is the Waterford crystal of plastic.” It’s not the same as the Old Weird America carnival and pay-by-the-ride parks. But their big budget does bring some nice frills. The sincere-vs.-lavish is one of things that Cory is getting at in Makers.

What does a ride stand for? What does it signify?

One simple idea is that a ride is as symbol for a story. People often refer to stories or novels as “wild rides.” You strap yourself in and go clickety-clacking off into the darkness of an author’s mind. Cory knows this, and he makes the connection quite explicit in Makers.

The main characters have set up a ride in a big abandoned building where you kind of drive around in little electric cars and look at exhibits. It’s like, as I say, the old ghost-house rides or maybe a little like the “It’s a Small World” ride. But you can steer your car to some extent. The ride isn’t about gravity or acceleration like a roller-coaster, it’s about looking at little scenes. Very much like a novel.

In Cory’s vision of a futuristic ride/novel, the users are continually changing the scenes. His final ride is like a physical wiki, indeed the ride is instantiated at multiple sites across the world, and the changes that the users make on any given site can be percolated out through the network to change all the other rides to match—taking advantage of those handy 3D printers and maintenance robots.

And the “story” sketched out by ever-mutating scenes of the final ride is one that’s emerged from the minds of all the users, acting in concert like an ant colony. This is a cool SF trope and I’d like to see it pushed further. In reality, I guess there must be some wiki-written fiction on the web, but I’m guessing it isn’t be very good—but maybe? Post a comment with a link to further-reading wikifiction links if know of any.

In some sense, film scripts are wiki-written, in that they have so very many inputs—but of course that’s in some sense the reason why most film scripts suck. To a mild extent, when you co-author a story with another writer, you’re getting into the emergent story zone. I recall that some of us tried writing a wiki-style story using Google Docs, and posted it as “Irene Leaves the Werehouse” on Flurb, but it has that disjointed feel of the classic dada/surreal “Exquisite Corpse” pictures.

Oh, here’s a flash: the so-called “news stories” that society presents us with are wiki-written fiction. News is the fiction that a society writes.

Cory’s got me thinking!