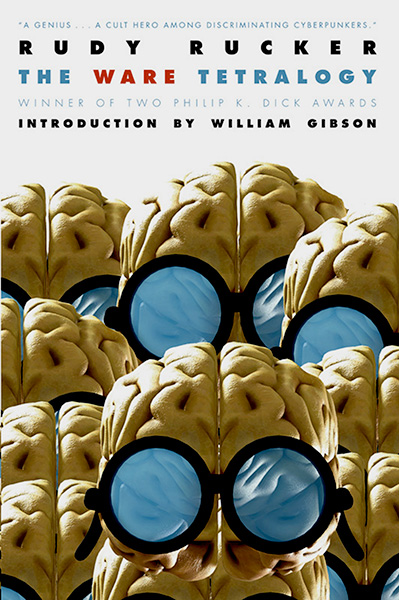

The Ware Tetralogy is now in print! I have more info about it with an excerpt and a podcast on an earlier post, “Monkey Brain Feast…Southern Style.”

I’ll drop in some blurbs for the four component novels here:

Software.

One of cyberpunk’s most inventive works.

— Rolling Stone.

Wetware.

Delightfully irreverent. This is science fiction as it should be: authoritative and tightly linked with our real lives and our real future.

— Washington Post Book World.

Freeware.

One of science fiction’s wittiest writers. A genius … a cult hero among discriminating cyberpunkers.

— San Diego Union-Tribune.

Eminently satisfying … intelligent and witty … the climax of what may well have been one of the most important SF series of the past 15 years.

— Washington Post Book World.

Much has been made of Rucker’s affinity with Dick, insofar as they both identify with and honor the common man, and both men write with a lucid simplicity that allows them to convey the weirdest ideas in the easiest to understand form. Rucker wishes — for himself, his characters, and everyone else — the maximum freedom that reality will allow.

— Isaac Asimov’s SF Magazine.

It is fast-paced, funny, and celebrates the complexity of the universe without dumbing it down. It adds up to a unique voice in SF, exuberant, vigorous and dense with strange but vividly realized ideas.

— Interzone.

Freeware is a fearlessly weird and very funny romp through a seedy, decadent 21st century America. Rucker’s evocation of the 21st century has an internal logic that provides a firm foundation for his gonzo inventiveness and dark humor.

— San Francisco Chronicle-Examiner.

Realware.

Rucker’s writing is great like the Ramones are great: a genre stripped to its essence, attitude up the wazoo, and cartoon sentiments that reek of identifiable lives and issues. Wild math you can get elsewhere, but no one does the cyber version of beatnik glory quite like Rucker. Rucker does it through sheer emotional force … it’s not his universes, it’s his people and how the relate to each other — and to the spiritual. That’s what Realware has going for it: healing and a calm sense of spirituality.

— New York Review of Science Fiction.

Strangeness is one of the main attractions of science fiction, and Rucker delivers plenty of it — exotic technologies, a funky future culture, mathematical head trips. Yet Rucker invests his main characters with surprising depth and complexity. From time to time the novel’s often madcap tone becomes unexpectedly serious, even tragic.

— SCIFI.COM

Rucker has written a generational saga that spans sixty years of mind-blowing change. Without sacrificing any of his id-driven wildness, Rucker has developed into a benevolent, all-seeing creator … Realware brings to a fully satisfying conclusion this landmark quartet.

— Isaac Asmiov’s Science Fiction Magazine.

Yeah, baby! Be diggin’ on the electric pig!

This weekend we happened to be in the SF Civic Center, and the Juneteenth festival was going on. One of the bands playing was Sila and the Afrofunk Experience . The lead singer, Victor Sila, is from Kenya, the ancestral home of President Obama. The band was great, hypnotic.

Almost the only other white person at this event was the guy running the sound board. It was unusual for me to be quietly sitting with this crowd, kind of liberating. Hardly anyone was eating or drinking anything, not consuming, just relaxing and enjoying the festival.

Later that night we went to a completely different kind of event, the SF Opera’s staging of Wagner’s Walküre, fully four and a half hours long, counting intermissions. During act two, while I was sitting there in my dress shirt, I felt something moving on my skin under my shirt. The next morning I figured out that I’d brought back four ticks from my walks in the woods in Kentucky.

[Downtown Lagrange, Kentucky.]

Wandering around in SF in the afternoon, we went into the Japanese tea garden in Golden Gate Park—if you actually live in the SF area, you tend not to go into this spot very often, as it’s something of a tourist attraction. But if you push through to the back, there a nice tiny Zen rock garden.

Near the garden was a statue of Buddha, with a spiderweb covering his face. That’s kind of where my writing muse is at these days, covered over, inactive. I’m still recovering from finishing the last novel, Jim and the Flims, I guess.

Another walled-off muse is in the Civic Center park—it’s this statue called “Three Heads Six Arms,” and the city has put a fence around it because people were writing graffiti on it, also they’re worried about people climbing on it. Supposedly the fence is temporary, and the web will blow away. Let’s hope so.