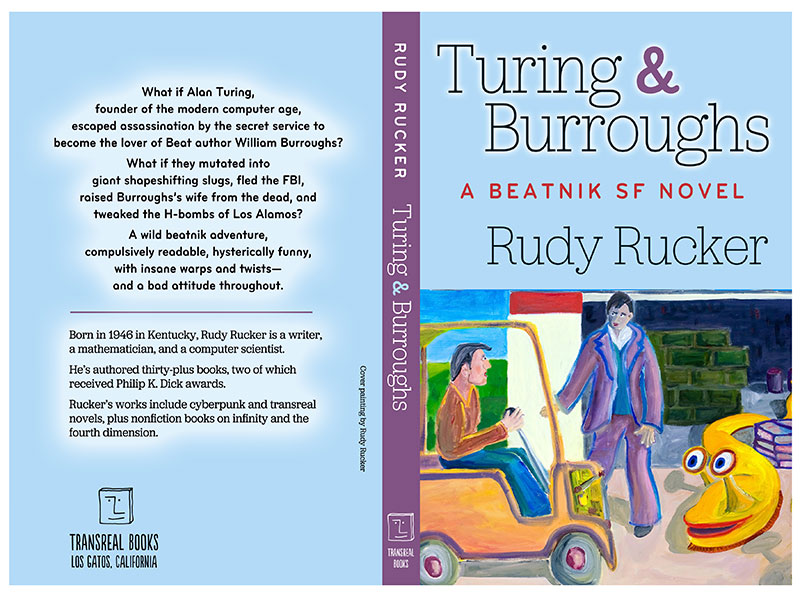

I’m presently working on a novel called The Big Aha in which I might have my characters be involved in a religion based on the experience of telepathy. The telepathy is brought on by a (SFictional) biophysics maneuver that I’m calling quantum wetware.

The idea of having a religion based on an actual physical phenomenon is intriguing. One model for this kind of sociocultural phenomenon would be the quasi-religious attitude of the first acidheads in the late 1960s. But in my novel want the movement to emerge from something other than drugs.

Over the years, I’ve thought of two religions whose birth I could be involved with. The first is The Church of the Fourth Dimension, an idea invented by the famed and beloved science writer Martin Gardner in one of his columns. Maybe I’ll blog about that another time.

The religion I want to post about today is what I might call Xiantific Mysticism. “Xiantific” has a nice sound to it—the rebellious leading X, the conflation with Christian=Xian, and the pronunciation Xiantific=Scientific. I called this “religion” Scientific Mysticism in my novel Master of Space and Time. It relates to my essay, “The Central Teachings of Myticism,” which I posted about a few days ago.

Here’s a passage from Master of Space and Time, featuring an encounter between my characters Joe Fletcher and Alwin Bitter. Alwin Bitter is actually a carry-over character from my earlier novel The Sex Sphere. And he’s a member of the Church of Scientific Mysticism.

Sunday morning we went to church, the First Church of Scientific Mysticism. The religion, vaguely Christian, had grown out of the mystical teachings of Albert Einstein and Kurt Gödel, the two great Princeton sages. My wife Nancy and I didn’t attend regularly, but today it seemed like the thing to do. According to the evening news, a giant lizard like Godzilla had briefly appeared on the Jersey Turnpike.

The sun was out, and the two of us had a nice time walking over to church with our daughter Serena.

The church building was a remodeled bank, a massive granite building with big pillars and heavy bronze lamps. Inside, there were pews and a raised pulpit. In place of an altar was a large hologram of Albert Einstein. Einstein smiled kindly, occasionally blinking his eyes. Nancy and Serena and I took a pew halfway up the left side. The organist was playing a Bach prelude. I gave Nancy’s hand a squeeze. She squeezed back.

Today’s service was special. The minister, an elderly physicist named Alwin Bitter, was celebrating the installation of a new assistant, a woman named — Sondra Tupperware. I jumped when I heard her name, remembering that my friend Harry Gerber had mentioned her yesterday. Was this another of his fantasies become real? Yet Ms. Tupperware looked solid enough: a skinny woman with red glasses-frames and a Springer spaniel’s kinky brown hair.

Old Bitter was wearing a tuxedo with a thin pink necktie. The dark suit set off his halo of white hair to advantage. He passed out some bread and wine, and then he gave a sermon called “The Central Teachings of Mysticism.”

His teachings, as best I recall, were three in number: (1) All is One; (2) The One is Unknowable; and (3) The One is Right Here. Bitter delivered his truths with a light touch, and the congregation laughed a lot — happy, surprised laughter.

Nancy and I lingered after the service, chatting with some of the church members we knew. I was waiting for a chance to ask Alwin Bitter for some advice.

Finally everyone was gone except for Bitter and Sondra Tupperware. The party in honor of her installation was going to be later that afternoon.

“Is Tupperware your real name?” asked Nancy.

Sondra laughed and nodded her head. Her eyes were big and round behind the red glasses. “My parents were hippies. They changed the family name to Tupperware to get out from under some legal trouble. Dad was a close friend of Alwin’s.”

“That’s right,” said Bitter. “Sondra’s like a niece to me. Did you enjoy the sermon?”

“It was great,” I said. “Though I’d expected more science.”

“What’s your field?” asked Bitter.

“Well, I studied mathematics, but now I’m mainly in computers. I had my own business for a while. Fletcher & Company.”

“You’re Joe Fletcher?” exclaimed Sondra. “I know a friend of yours.”

“Harry Gerber, right? That’s what I wanted to ask Dr. Bitter about. Harry’s trying to build something that will turn him into God.”

Bitter looked doubtful. I kept talking. “I know it sounds crazy, but I’m really serious. Didn’t you hear about the giant lizard yesterday?”

“On the Jersey Turnpike,” said my wife Nancy loyally. “It was on the news.”

“Yes, but I don’t quite see — ”

“Harry made the lizard happen. The thing he built — it’s called a blunzer — is going to give him control over space and time, even the past. The weird thing is that it isn’t really even Harry doing things. The blunzer is just using us to make things happen. It sent Harry to tell me to tell Harry to get me to — ”

Bitter was looking at his watch. “If you have a specific question, Mr. Fletcher, I’d be happy to answer it. Otherwise … ”

What was my question?

“My question. Okay, it’s this: What if a person becomes the same as the One? What if a person can control all of reality? What should he ask for? What changes should he make?”

Bitter stared at me in silence for almost a full minute. I seemed finally to have engaged his imagination. “You’re probably wondering why that question should boggle my mind,” he said at last. “I wish I could answer it. You ask me to suppose that some person becomes like God. Very well. Now we are wondering about God’s motives. Why is the universe the way it is? Could it be any different? What does God have in mind when He makes the world?” Bitter paused and rubbed his eyes. “Can the One really be said to have a mind at all? To have a mind — this means to want something. To have plans. But wants and plans are partial and relative. The One is absolute. As long as wishes and needs are present, an individual falls short of the final union.” Bitter patted my shoulder and gave me a kind look. “With all this said, I urge you to remember that individual existence is in fact identical with the very act of falling short of the final union. Treasure your humanity, it’s all you have.”

“But — ”

Bitter raised his hand for silence. “A related point: There is no one you. An individual is a bundle of conflicting desires, a society in microcosm. Even if some limited individual were seemingly to take control of our universe, the world would remain as confusing as ever. If I were to create a world, for instance, I doubt if it would be any different from the one in which we find ourselves.” Bitter took my hand and shook it. “And now, if you’ll excuse me, I’ve got to get home for Sunday dinner. Big family reunion today. My wife Sybil’s out at the airport picking up our oldest daughter. She’s been visiting her grandparents in Germany.”

Bitter shook hands with the others and took off, leaving the four of us on the church steps.

“What’d he say?” I asked Sondra.

Sondra shook her head quizzically. Her long, frizzed hair flew out to the sides. “The bottom line is that he wants to have lunch with his family. But tell me more about Harry’s blunzer.”