I recently did three interviews in connection with Million Mile Road Trip. One was with the writer Jeff Somers from B&N SciFi & Fantasy Blog. One was a fixed list of questions (so call my interviewer “Bot”), from Shelf Awareness webzine. And the third was a single-question interview by Chris Richards a pop music writer at the Washington Post, who publishes a rather amazing little zine called Debussy Ringtone — in print only. As usual I’m putting in a surreal mix of recent photos, and I’ve included two recent paintings (with notes) as well.

Jeff. Night Shade Books calls this the “Year of Rudy Rucker,” which feels way overdue. You’ve published 23 novels—where would you recommend a Rucker newbie get started

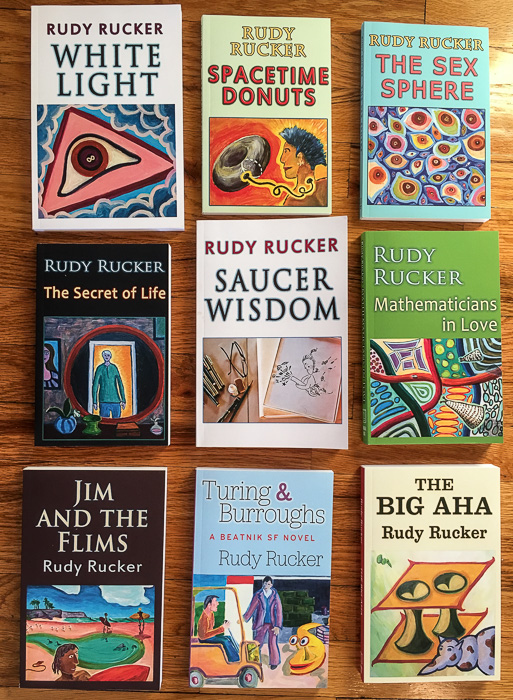

A. Yep, Night Shade is issuing ten books by me this year—nine reprints along with Million Mile Road Trip. A matching set of print books with great covers. I’m not sure I’d say this is way overdue, but I’m really glad it’s happening. If you’re an author, having your books in print is the blood of life. Which of my books to start with? Whichever one you get your hands on. I do like Mathematicians in Love a lot..And Saucer Wisdom is a hoot. But this week I’m gonna say that Million Mile Road Trip is a good place to start! Could be the best book I ever wrote.

[This is the same pink IBM Selectric model that I wrote my first few novels of. Seen in the Milwaukee Art Museum Design section.]

Jeff. Your companion book, Notes for Million Mile Road Trip, is actually longer than the novel! The idea of following up reading a novel with that kind of metadata is fascinating; can you tell us more about it?

A. It’s hard to write a novel. It takes a year or maybe two years of tickling the keyboard at your desk, or using a laptop in a cafe, doing that pretty much every day, even on the days when you don’t know what comes next. This is where writing a volume of notes comes in. When I don’t have anything to put into the novel, I write something in the notes. I might analyze the possibilities for the next few scenes. Or craft journal entries about things I saw. Or describe some the people sitting around me, being careful not to stare at them too hard. Or wheenk about how hopeless it is to try to write another novel, and how I’ve been faking it all along anyhow. The more I complain in my notes, the better I feel. I publish the finished Notes in parallel with with the novel, not that I sell many copies of the notes. Longterm, the notes will be fodder for the locust swarm of devoted Rucker scholars who are due to emerge any time now from their curiously long gestation in the soil.

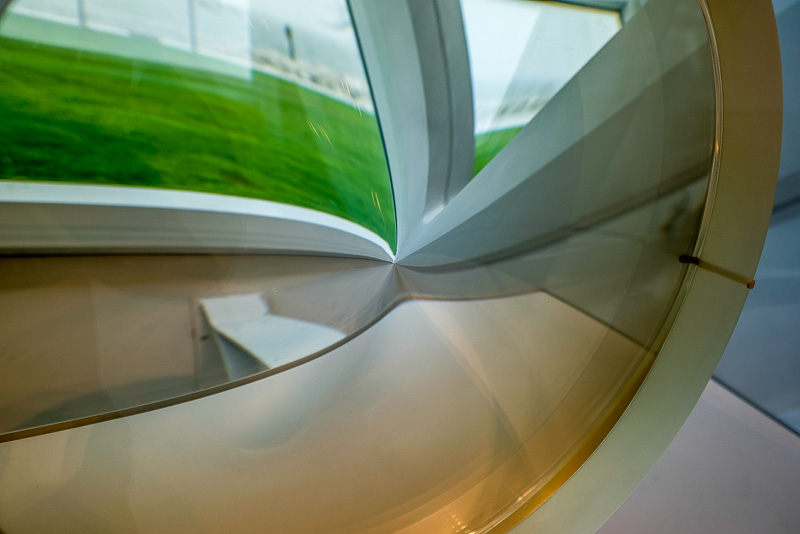

[Fresnel Lens for the lighthouse at Point Arena, CA.]

Jeff. What’s amazing about a book like MMRT is how you take some pretty high-level math and science and turn it into a rollicking sci-fi adventure. How do you manage that balance?

A. I studied math in college and grad school. Math always appealed to me. So clear and so intricate—the hidden machinery of the world. It is, as you say, a delicate balance to have a book be lively, with romance and fun characters—and also to have it be based on logical science ideas. In studying math, I learned about starting out with some set of assumptions like, say, Euclid’s postulates or the axioms of transfinite set theory, starting out with a set of rules and then deducing what follows from them. In my SF novels, I’ll make some wild, far-out initial assumptions. But from then it’s logical, and I get to see what ends up happening. I don’t really know in advance, not before I write the novel. That way its surprising and fun. I’m not trying to teach things to my readers. I want them to be amazed and to laugh and to be carried away.

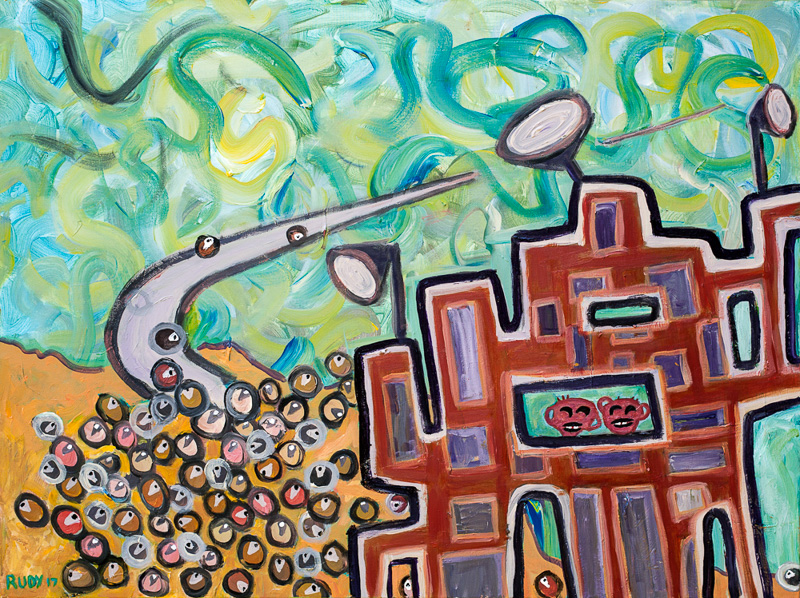

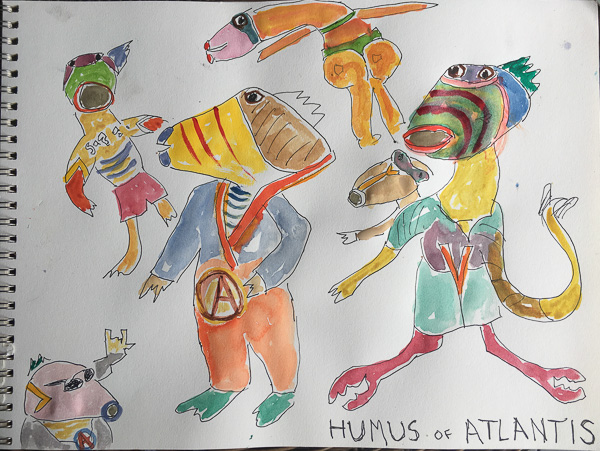

“Cute Meet” Acrylic, pair of 24″ x 30″ canvases, May, 2019. Click for a larger version of the painting.

[I saw a diagram of a so-called Hele ”Shaw ferrohydrodynamics pattern formed by, I don’t know, something like a rotating magnetic field under a fluid with metal dust in it. I don’t remember the details. But I liked the cool pattern. I love when nature makes these chaotic, odd things that look like paleolithic cave-wall drawings. So I picked one pattern, and painted two versions of it, copying the pattern by hand each time. I liked doing it so much that I did it twice, so we have a diptych here. And the colors are kind of the opposites of each other. And if you rotate either of these patterns by 180 degrees, it’s approximately the same as the other one. So they’re the same species. But the butterfly one on the left is girl, and the yearning one on the right is a boy. And they’re having a cute meet.]

Debussy. Most of your novels and stories are optimistic. Why?

A. The media are awash with bad news. But this is a custom, and not a reflection of reality. My theory is that bad news (a) makes people more fearful and more likely to accept repressive rulers, and (b) makes them more likely to buy distracting expensive things. Media, the Man, and Mammon work in concert. It’s not really true that the world is worse off than it’s ever been. Flip back through history, and things are always a mess. We’re all going to die. That never changes. Why obsess on it? I prefer to have some fun in the time that I have. And to hell with the daily news.

When I’m writing an SF story, I’m describing an alternate world that I’m inventing on the spot. I want to see interesting characters, good dialog, rad mind warps, surprising plot twists, rich vocabulary, eyeball kicks, and unheard-of science. I’m like a painter who prefers bright colors to blacks and grays. There’s good as well as bad. Unknown natural laws await. Aliens might be friendly. A novel can have a happy ending.

This said, I’m not above killing off a main character in any given book. You need chiaroscuro, that is, some dark against the like. It’s nice to pump up a big operatic scene where a good person dies. But, do note that I do like someone’s death to be a big deal—and not just have a stranger shoot a person in the back of the head and have everyone be, like, “Oh, sigh, that’s the way it is in this boring vale of tears, and now let’s parrot some media headlines.”

I think you said you only wanted three hundred words for my answer? Wow, that’s not many! I’d hoped I’d be able to go on and write about—erk

Bot. Your favorite books when you were a child?

A. I loved the world of C. S. Lewis’s Narnia books. And Beverly Cleary books like Ribsy, Henry Huggins, and Ramona the Pest. And a picture book by Robert Lawson, McWhinney’s Jaunt—about a professor who rides across the country on a flying bicycle, held aloft by “Z gas” in is tires. I read all the Robert Heinlein novels, and especially liked Revolt in 2100 and Tunnel in the Sky. I was a huge fan of the SF master Robert Sheckley’s Untouched by Human Hands. And when I was fourteen, I got hold of the Beat author William Burroughs’s Naked Lunch, which I found on my big brother’s bookshelf. Burroughs showed me that you can write about anything at all.

Jeff. You’ve been called a groundbreaker in genre—from your foundational writing in cyberpunk and transrealism, to being the winner of the first Philip K. Dick Award ever. What’s your take on the modern state of sci-fi, and what do you see for the future of the genre?

A. I’m not much involved with factions and fashions in the SF community—although I do have my old cabal of cyberpunks, transrealists, and the writers I published when I was running my webzine Flurb. An odd recent phenomenon is that lots of mainstream authors are writing SF. But they won’t admit it’s SF. Lifelong literary-SF writers like me find this … irritating. It’s like the upper crust authors can dip down into our world—but they don’t want to let us out. Even if we’re writing high lit. I always think of Kurt Vonnegut’s line, “I have been a soreheaded occupant of a file drawer labeled ”˜science fiction’ … and I would like out, particularly since so many serious critics regularly mistake the drawer for a urinal.”

[Above: Model of my character Groon from Million Mile Road Trip. Model by Chuck Shotton, painstakingly 3D-printed, and with a sound chip inside. My painting of Groon in the background. Below: With artist Paul Mavrides at the Andy Warhol show in San Francisco. That’s Mrs. Warhola in the background.]

Bot. What book do you most want to read again for the first time?

A. A volume of stories by Jorge Luis Borges. Labyrinths, say, or Collected Fictions. When I first read Borges, I was stunned at the richness of the trove. “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” might have been the very first of his stories I found. It’s a crazy-sounding title, but that’s as it should be. The tale is about the discovery of an encyclopedia about an unkown planet with “its emperors and seas, its minerals and birds and fish, its algebra and fire, its theological and metaphysical controversies.” All this in a single short story! And “Funes the Memorious,” where Borges describes a youth with a perfect memory. “He knew the forms of the clouds in the southern sky on the morning of April 30, 1882, and he could compare them in his memories with the veins in the marbled binding of a book he had seen only once, or with the feathers of spray lifted by an oar on the Rio Negro on the eve of the Battle of Quebracho.” Borges stories are my notion of what fantasy and science fiction ought to be. Truly other, and utterly wondrous.

Jeff. It’s been thirty-six years since you published A Transrealist Manifesto, and some argue that with the mainstreaming of sci-fi into popular-culture transrealism, we’ve reached a turning point where transrealism will soon be the baseline for sci-fi stories. Do you agree, or is it more complicated than that?

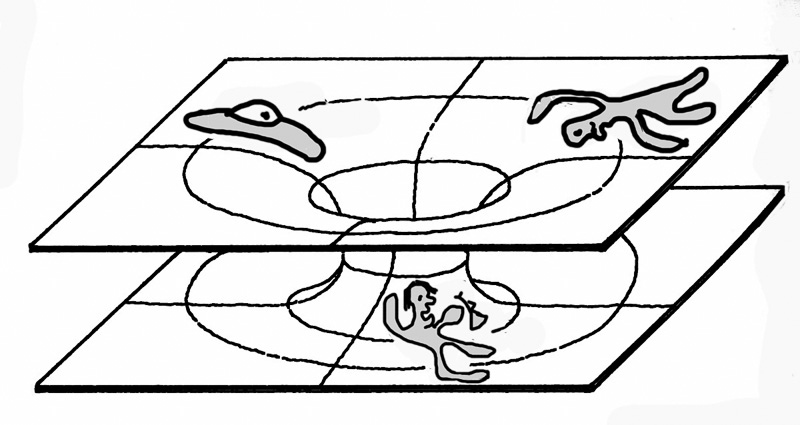

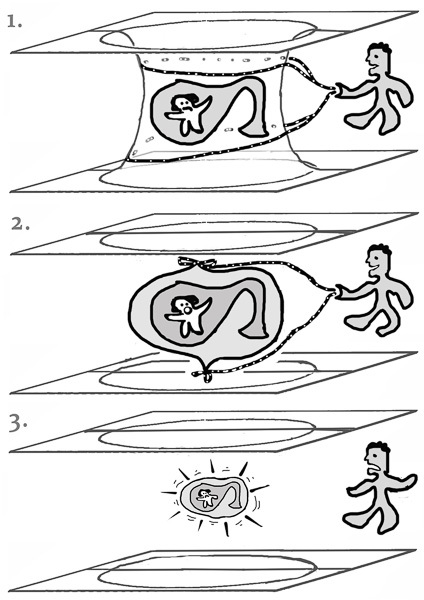

A. The idea behind transrealism it that you write in a fairly realistic way about your life and your feelings and about the lives of those around you—but then you bring in SF elements that can stand for subtextual aspects of your mental life. Like time travel stands for nostalgia and hope. And uploading your mind to a computer stands for going to heaven. And telepathy stands for someone actually understanding what the eff you’re talking about. And alien stands for people from different backgrounds. When you come down to it, everyone’s background is different, and everyone you ever meet is an alien. Or maybe a zombie or a robot. The SF tropes are objective correlatives for things we have trouble writing about. And, yes, this transreal approach can be a baseline for present-day lit.

Bot. Books you’d still like to write?

A. I want to write about a heretofore unnoticed force of nature. It’s at the subquantum level. It relates to dark energy, and to consciousness. And once we get it tune with it, we’ll have all the free energy we need, and we’ll be able to live inside electrons, like in my novel Jim and the Flims, and to predict the future from soap films, like in Mathematicians in Love, and to levitate, like in Million Mile Road Trip, and to talk to rocks, like in Hylozoic. But I know there’s something more than even that, something wilder and deeper, something super new that will, in retrospect, seem obvious and natural. We’ll be, like, “Why didn’t we think of that before!” I hope the muse shows it to me.

[Detail from Peter Bruegel’s Het Luilekkerland, also known as Schlaraffenland or The Land of Cockaigne.]

Bot. A book you hid from your parents?

A. I grew up in Kentucky, and in the University of Louisville bookstore I found a text on types of mental illness. As a budding young author, I had to consider the option of going mad as an early career move. I got the book, and I’d look through it to find symptoms that I might be having, or that I might be able to convince myself that I had. It drove my parents nuts to see me do that. As if I weren’t already enough trouble!

“The Two Lovers Walk Their Dog” acrylic on canvas, June, 2019, 30” x 24”. Click for a larger version of the painting.

[They had an En Plein Air painting festival in my town, and I was thinking I should do a quick painting of something I saw outside. So I went in my backyard and started painting the ivy leaves on the wall. And that got a little boring. So I started putting in critters. I made a spiraling black line, and then I put an eye in the middle, and that’s how I got started on the figure on the right. I gave her pink flesh, and put in some 3D shading to round her out. the real stroke of inspiration was just filling in a crescent of orange-red for her mouth. And then I drew her lover on the left. His smile is even bigger. And the dog? Well, he was just a lucky hit. I made that red glob and put two things like ears on it, and then added another—voila! And I made the background an insanely bright and saturated shade of yellow-orange. I love how cheerful the lovers look. And the ivy leaves turned out to be hearts. And, all in all, there’s seventeen eyes bobbling around! This one is a gift from the Muse, an unexpected masterpiece. Not that it would ever be accepted by the En Plein Air festival. But who cares.]

Jeff. You also paint, and have received notice for your artwork, which favors surreal sci-fi themes. Are there connections between your painting and your writing?

A. I started painting in 1999 because I was writing a historical novel, As Above, So Below, about the life of the artist Peter Bruegel. I wanted to get a sense of what it’s like to paint. Over time I got to enjoying it more and more. I’ve done almost a hundred and seventy paintings by now. I’m not a great draftsman. But with paint, you can push it around and layer it until it looks like what you want. And then of course you ruin it, and fix it, and ruin it again, and fix it, and eventually you stop.

I like how painting is completely analog. No keyboard and screen. Smearing paint on a canvas. I love it. When I’m unsure about an upcoming scene in a novel, I do a painting that relates to it. Not an exact representation, more like an evocation. Like dreaming while I’m awake. Writing is like dreaming, too. You get out of your way and type.

Bot. What are five books you’ll never part with?

A. Oh, let’s just do one. A fat one. Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. I reread it ever five or ten years, reveling once again in the man’s wit, and the richness of his prose. I’ve persistently been trying to write like Pynchon over the course of my twenty-three novels, and in Million Mile Road Trip, I think I finally got close. Some Pynchonian elements: Write in the present tense, like a person describing a movie. Use close-in third person viewpoint where thoughts of the focus characters spill onto the page. Use some very long sentences, with phrase after phrase being added on, like you’re a carpenter working your way out on an increasingly rickety scaffolding that you’re assembling as you go along. And allow yourself an occasional fourth-wall-breaking exclamation, like, “Maybe this is going a little too far.”

[Work by the artist Rina Banarjee.]

Jeff. You’ve been a professional writer and a publisher for decades; how has the business of getting your words out there changed in that time?

A. The biggest new thing is the ebook. Ebooks are literary immortality; they don’t ever go out of print. And writers can publish ebooks themselves for free. Not only that, writers can publish print books for free, too. And you can sell your self-published ebooks and paperbacks on big online sites such as Barnes & Noble. Personal freedom to publish to the world audience is a huge deal. No gatekeepers.

The catch, however, is that if you self-pub, it’s hard getting people to notice you. Including my nonfiction, I’ve published about forty books. And the first thirty or so were from commercial publishers. But in 2012, the publishers temporarily turned their backs on me. Like, “We’ve heard enough out of you!.” But I wasn’t ready to quit. And thanks to the new channels, I didn’t have to. I learned how to self-pub my own ebooks and paperbacks—I did my Collected Stories, my Journals, three novels, and an art book. I call my imprint Transreal Books. I ran Kickstarters for the self-pub books, which took the place of getting publishers’ advances. It was a lot of work.

And now, hallelujah, Night Shade Books has taken me into their fold. I’m back in the tribe and off the ice floe. I’m glad.