I feel like I’m the only person I know who saw the movie version of Kerouac’s On the Road recently. I liked it a lot, I saw it twice—the first time on it’s release date, which was also my 67th birthday.

[Photo I took on one of our own Wild West road trips, first posted 2010.]

The movie didn’t get much publicity, and it wasn’t in the theaters very long. Hard as it is for this old geezer to believe, most people in the younger movie-going generation haven’t even heard of On the Road, and they have only a hazy notion, if any notion at all, of who Jack Kerouac was. Father Time plows us under.

The movie includes a lovely 1949 Hudson car that Jack Kerouac, Neal Cassady, Luanne Henderson and Ed Dunkel drive from NYC to Algiers, Louisiana to visit William Burroughs, and then on to San Francisco.

As it happens, this very car, the one used in the film, is on display in the Beat Museum in San Francisco, just across Columbus Ave from City Lights Books. You can see the car for free, and if you pay a couple of bucks you can go in and see such Shroud-of-Turin level relics as Jack’s plaid coat.

Thinking about On the Road, I happened to recall a great passage in Chapter 11 where Jack describes him and Neal spending a night sleeping in an all-night movie theater in Detroit. I found the book online as one giant webpage, and searched that to find the key word “osmotic.”

For thirty-five cents each we went into the beat-up old movie and sat down in the balcony till morning, when we were shooed downstairs. The people who were in that all-night movie were the end. Beat Negroes who’d come up from Alabama to work in car factories on a rumor; old white bums; young longhaired hipsters who’d reached the end of the road and were drinking wine; whores, ordinary couples, and housewives with nothing to do, nowhere to go, nobody to believe in. If you sifted all Detroit in a wire basket the beater solid core of dregs couldn’t be better gathered. The picture was Singing Cowboy Eddie Dean and his gallant white horse Bloop, that was number one; number two double-feature film was George Raft, Sidney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre in a picture about Istanbul. We saw both of these things six times each during the night. We saw them waking, we heard them sleeping, we sensed them dreaming, we were permeated completely with the strange Gray Myth of the West and the weird dark Myth of the East when morning came. All my actions since then have been dictated automatically to my subconscious by this horrible osmotic experience.

Love that last sentence.

Onward. These days, as I’ve been mentioning, I’m working on a novel called The Big Aha, and I’m nearing the end. And I want to come up with an explanation of what I mean by the psychic state that I call “the Big Aha.”

What I term the “cosmic mode” in the novel is an intuitive, immediate knowledge of the world — what we might call a mystical grasping of the world in its unity. A characteristic feature of cosmic-mode knowledge is that it avoids distinguishing between the knower and the known, the subject and object. You see the world as One.

In what I call the ”robotic mode”, we have a discursive, analytical knowledge of the world — rational thought. In the robotic mode you stand apart from the thing known. You see the world as Many.

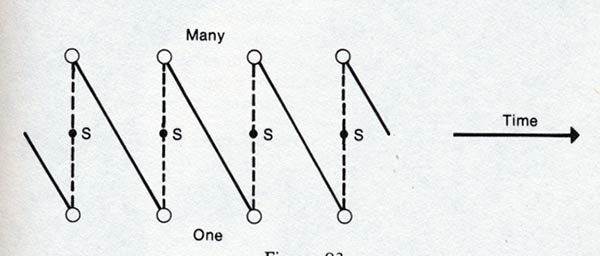

The point is not that mystical, all-is-One, cosmic-mode knowledge is preferable. Both the cosmic and robotic modes of knowledge are real, and both are important. But it is very hard — perhaps impossible — for us to see the world in both ways at once. At any instant we see the world either as One or as Many.

Moving from Many to One tends to be a gradual process, the result of some kind of deliberate calming of the mind. But the passage from One to Many is usually sudden. At a given instant you may be sunk into a complete unity with the world. And then an instant later you are talking about your experience, standing outside yourself, making distinctions. The difficult thing is to catch the instant when you are still between One and Many. I sometimes think of this instant as the slash mark in the One/Many problem, that is the problem of how the world can be both One and Many at once.

[World seen through my legs while doing yoga.]

In his essay, “The Meaning of Satori,” which appears in his book The Field of Zen, the author D. T. Suzuki says this instant is the fleeting enlightenment that Zen calls satori. “The oneness dividing itself into subject/object and yet retaining its oneness at the very moment that there is the awakening of a consciousness — this is satori.”

This sort of satori is fleeting, but not rare. One could almost say that the natural rhythm of thought is an oscillation between One and Many. As you look around the room there are constant microlapses of attention. You reach out and merge with the world, then draw back and analyze. At one instant there is only is-ness, at the next there is a person cataloging his perceptions. One-Many-One-Many … at a rate of, say, three cycles per second.

Here’s a picture of this taken from my nonfiction book Infinity and the Mind, my bestselling book ever. It represents the mind of indicating a person who repeatedly sinks down into blissful union with the One, only, each time, to snap back to ordinary rational consciousness. The points labeled “S” might be the satori points.

There is a sense in which waking up each morning is a satori. On a good day (no alarms, no clock to punch) you float up from sleep into an idle state of is-ness, not even thinking who or where you are. But this is too good to last . . . whisk clickety-click, and you’re planning your day Is it possible to notice the moment of switch-over?

When I was doing my research for book Infinity and the Mind, I came across a guy called Benjamin Paul Blood who was, one might say, one of the first-ever drug-mystic’s in the United States. He would equip himself with a handkerchief soaked in ether, hold it to his face, sink into unconsciousness, and then, as his nerveless hand fell away, he would wake back up. The experience of moving abruptly from artificial trance to normal awareness struck him as central, and he wrote something very interesting about it in an 1874 pamphlet, The Anaesthetic Revelation and the Gist of Philosophy. In the long quote below, I added three little clause numbers to make it easier to follow what he’s saying:

I think most persons who shall have tested it will accept this as the central point of the illumination: [i] that sanity is not the basic quality of intelligence, but is a mere condition which is variable, and like the humming of a wheel, goes up or down the musical gamut according to a physical activity; [ii] and that only in sanity is formal or contrasting thought, while the naked life is realized only outside of sanity altogether; [iii] and it is the instant contrast of this tasteless water of souls with formal thought as we “come to” that leaves in the patient an astonishment that the awful mystery of Life is at last but a homely and a common thing, and that aside from mere formality the majestic and the absurd are of equal dignity.

Satori, man.

Up until now I have been describing the interface between One and Many as something that one moves back and forth through in time. This is a bit misleading. In Suzuki’s words, “Satori is no particular experience like other experiences of our daily life. Particular experiences are experiences of particular events while the satori experience is the one that runs through all experiences.”

In other words, the One and the Many run about together in and out of every word ever uttered. The world is One and the world is Many. The One/Many split is the heartbeat of the universe, the charged tension that makes things happen.

What happens in my novel The Big Aha is that my characters find a way to “jam open” the switch between the cosmic and the robotic mode, and they stay in cosmic mode for long periods of time, being One with reality, but without losing their ability to function.

And that’s the Big Aha experience that my book’s title is referring to. The Big Aha is that you can remain in cosmic mode and not be flipping out about it.

In writing my novel, I’d had some faint hope of finding a “higher” Big Aha in an alternate world that my characters visit. But I ended up with more of a D. T. Suzuki or Benjamin Paul Blood routine. Although your knowledge of the Big Aha may be sparked by some a unique and a trippy White Light experience, it ends up being being a part of daily life. You recognize the fact that you’re in the cosmic “All is One” mode a lot of the time.

This is all there is. What was I so excited about? What else did I expect?

Coming at this form of the Big Aha from another angle, think of what the great science writer Martin Gardner calls the “superultimate why question” in his essay, “Science and the Unknowable.” You start with, “Why does anything exist?” And, given any answer to that, you can say, “But where did that come from?” So you might as well short-circuit the process. There is no explanation beyond what we’re experiencing here and now.

So….the Big Aha is? Be here now. Mindful. In the now moment.

You figure out the secret of life—fine. But you still have to go ahead and lead the whole rest of your life. Living in the Big Aha.

April 29th, 2013 at 4:35 pm

I see your distant relative G.W.F. leaking through the generations here. From Jonathan Sperber’s Karl Marx, explaining Hegel; “A subject’s consciousness of objects outside itself would ultimately be transformed into an expanded version of self-consciousness…the individual perceiving subject would come to understand its self-consciousness as part of a cosmic, collective subject….”

Just sayin.

May 5th, 2013 at 2:15 pm

Mike G, nice to hear from you. I don’t often think of that, but it could well be that there’s a genetic component to my lifelong fascination with thoughts of “the One.” Odd how we imagine that our philosophical positions are arrived at for precise logical or emotional reasons, when in fact they may simply be wired into our wetware. I’d expect my eye color or my brain-size to be gentically determined, but not my closest-held ideas!

Oh, well, I feel like they’re “right” anyway. Right in the same sense that an old shoe is a comfortable fit.

Thinking of you, I always recall various fun times. Conversing via squeaks in the floorboards that we made by jiggling up and down. Drinking beer together while wedged into forks in two tall adjoining trees by the autum-leaf dappled James River. Hope all’s well!

June 11th, 2013 at 12:39 pm

Having never been a Kerouac fan I may be biased, but I don’t think Father Time will be plowing “Naked Lunch” under. Great books don’t go away just due to time passing. Although maybe overrated ones do.