As I’ve mentioned, my wife Sylvia died eleven months ago, and I have to find ways to fill the empty time at home. Somehow I still haven’t gotten back to writing stories and novels. I paint in the daytime, and I watch a fair amount of TV in the evening, but I get sick of that, so I’m reading a lot.

Recently I went to good old Bill Gibson’s Neuromancer, and then went and read Count Zero and Mona Lisa Overdrive. They call this the Spawl Trilogy now, the Sprawl being the fused coast city that runs from Boston to Atlanta.

I read on my Kindle these days, and a nice feather of this device that you can highlight passages, and then download the passages to a single text file. So for today’s post, I’m presenting my Sprawl highlights along with a few comments.

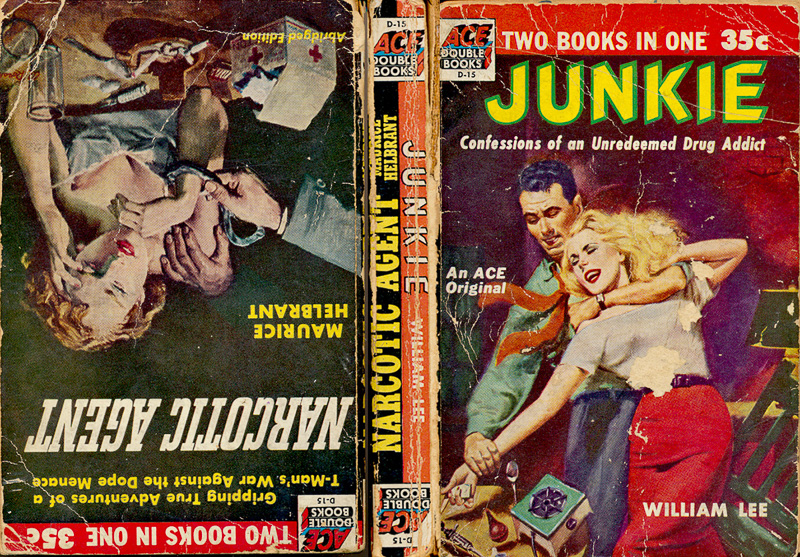

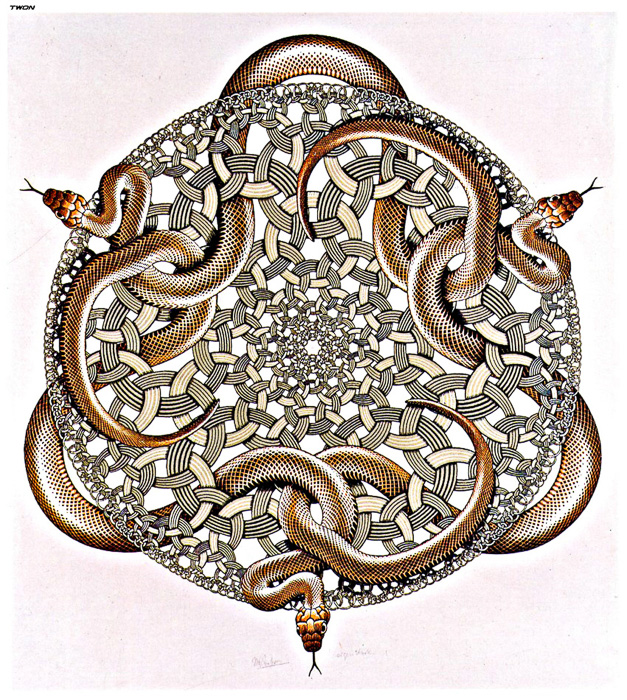

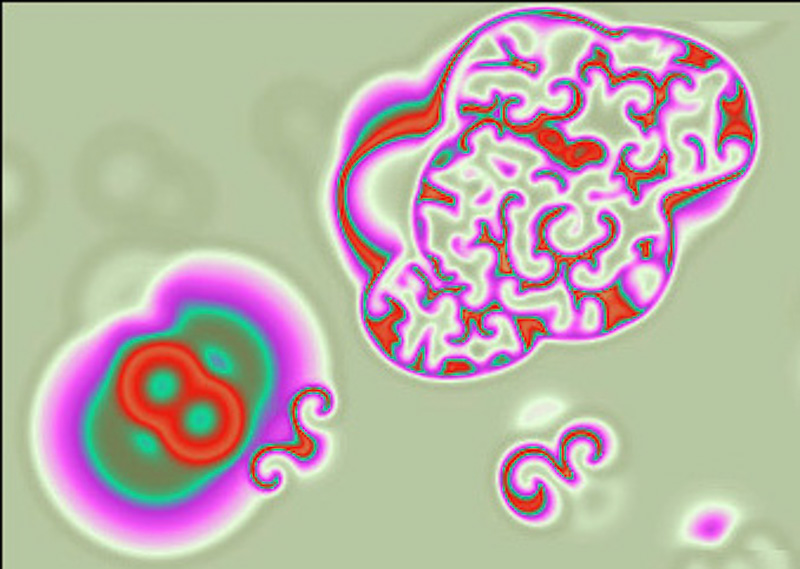

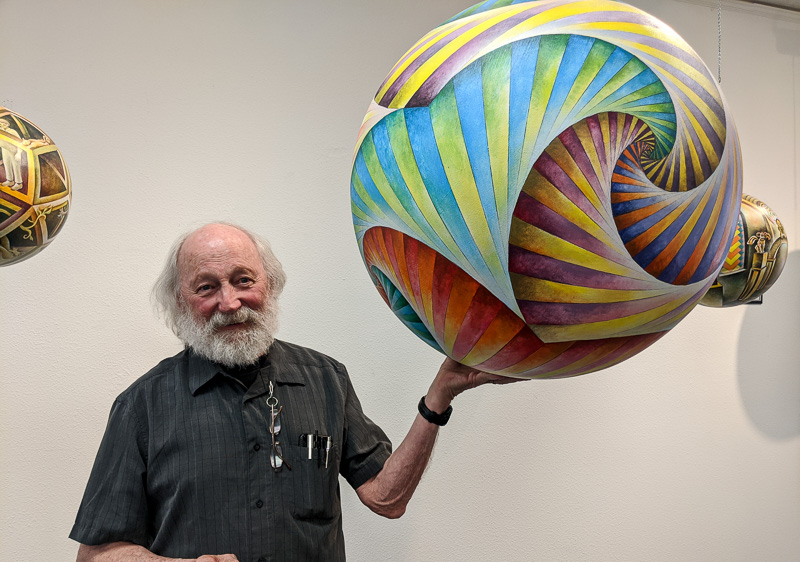

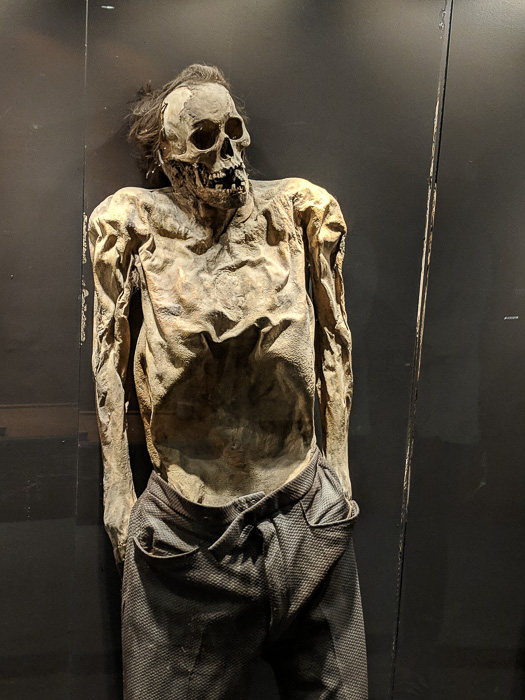

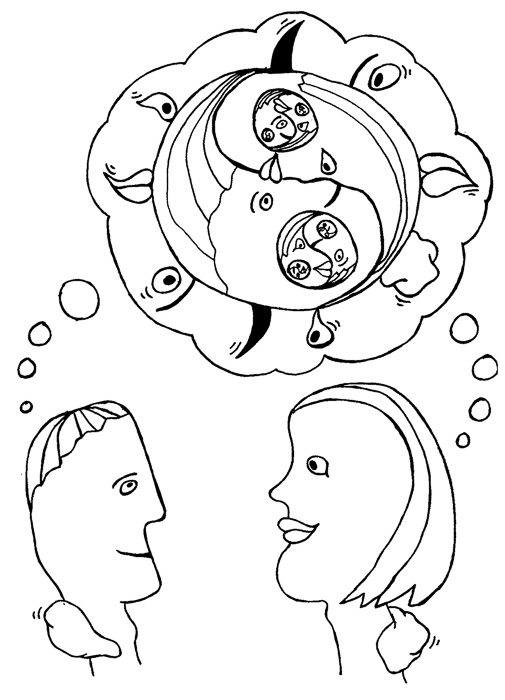

And I put in randomly photos from my stash. As I always say: the fundamental principle of Surrealism is that anything goes with anything. And meaningfully so.

I’ve used the Book Notes format for a blog post several times before. It’s a way of thinking more deeply about books that I love. Here are the six prior posts like this that I’ve done.

David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest.

Cory Doctorw’s Walkaway

Christopher Brown The Tropic of Kansas

Several novels by Raymond Chandler.

Gibson’s The Peripheral.

Gibson’s Agency. This post includes comments by Gibson himself.

And now for the Sprawl trilogy! I’ve provided page numbers for of the quotes, but with Count Zero, I ended up with “location numbers,” which only make sense if you’re reading a book on a Kindle. In any case, you can always find a passage in an ebook by searching for a key word or phrase.

Neuromancer

Page 8 —…her upper lip like the line children draw to represent a bird in flight.

There’s several things that make Bill’s writing great. One is that he has the ear of a poet. He turns lovely phrases akin to haiku. But there’s more than that. He’s an expert at getting your to have total sympathy for his down-and-out or drug-addicted or oppressed characters. Rooting for them! And if they’re in some way childish, so much the better. Nobody understands them! They’re just like me! Those are the kinds of characters that I like to write too.

Page 103

“How you doing, Dixie?” “I’m dead, Case. Got enough time in on this Hosaka to figure that one.” “How’s it feel?” “It doesn’t.” “Bother you?” “What bothers me is, nothin’ does.” “How’s that?” “Had me this buddy in the Russian camp, Siberia, his thumb was frostbit. Medics came by and they cut it off. Month later he’s tossin’ all night. Elroy, I said, what’s eatin’ you? Goddam thumb’s itchin’, he says. So I told him, scratch it. McCoy, he says, it’s the other goddam thumb.” When the construct laughed, it came through as something else, not laughter, but a stab of cold down Case’s spine. “Do me a favor, boy.” “What’s that, Dix?” “This scam of yours, when it’s over, you erase this goddam thing.”

The Dixie Flatline is one of the lovable characters here. A former “cowboy” or cyberspace explorer he’s known for having effectively died during one of his sessions…and then bouncing back. The sign of his being temporarily dead is that the monitor of his brave waves collapsed to zero, to a flat line.

In Neuromancer, Dixie really is dead, but in a way he’s alive…as a construct or lifebox model of himself in cyberspace. Philosophers and SF people like to debate how it would feel to be a commuter simulation. And Dixie comes up u with a great, original answer. SF writers can out-do philosophers. We’re conducting thought experiments.

Page 114 — Holograms twisted and shuddered to the roaring of the games, ghosts overlapping in the crowded haze of the place, a smell of sweat and bored tension. A sailor in a white t- shirt nuked Bonn on a Tank War console, an azure flash.

Nice scene-setting here. A classic motif, the game arcade. With lovely sensory overlay, and a little touch of future history.

Page 115 — crumpled yellow candy wrapper, balanced on the edge of a console, dropped to the floor and lay amid flattened butts and styrofoam cups.

More haiku-like scene setting

Page 128 — the minute, I mean the nanosecond, that an AI starts figuring out ways to make itself smarter, Turing’ll wipe it. Nobody trusts those fuckers, you know that. Every AI ever built has an electromagnetic shotgun wired to its forehead.”

Interesting to read this in 2023, when the so-called doomers are worried sick about our ever-improving AI might in some way take over the world and ruin our lives. See my recent “Roaring Twenties” post with John Walker.

But the metaphor of “shotgun to the head” is hopelessly outdated. Our new AIs don’t “live” anywhere in particular. They are techniques that are instantiated all over the place, in machines and in cloud processes.

Page 143 — “I wasn’t conscious. It’s like cyberspace, but blank. Silver. It smells like rain. . .

That lovely language. Full-court-press on the Sensorama, pushing all the buttons.

Page 148 — The drug hit him like an express train, a white-hot column of light mounting his spine from the region of his prostate, illuminating the sutures of his skull with x- rays of short- circuited sexual energy. His teeth sang in their individual sockets like tuning forks, each one pitch- perfect and clear as ethanol. His bones, beneath the hazy envelope of flesh, were chromed and polished, the joints lubricated with a film of silicone. Sandstorms raged across the scoured floor of his skull, generating waves of high thin static that broke behind his eyes, spheres of purest crystal, expanding. . . .

Inventing a really terrific future drug is a hallowed SF trope. Reading about it gets you high. In a sense it’s like a mantra for a meditation routine. In reality, drugs tend not to live up to their advance billing, but every now and then you might get to a place like this. The error would lie in trying over and over to revisit it.

Page 149 — He seemed to become each thing he saw: a park bench, a cloud of white moths around an antique streetlight, a robot gardener striped diagonally with black and yellow.

Love this one so much. Kind of an LSD thing, I’d say. Merging with the world around you. Heavenly. But youthful drug experiences are like a country you used to live in, but which you can’t revisit…as that land has a death warrant out on your ass. This said, you can still re-enter the merged state while straight and sober. Takes some years of practice at being high instead of getting high,

Page 154 — “You are busted, Mr. Case. The charges have to do with conspiracy to augment an artificial intelligence.

Here again we have a kind of prediction about the future of AI. But now this particular line seems comical. Like something you’d hear in a Firesign Theater skit. I think the issue that we don’t in any sense have real control over where AI is going. Yes, you can fire your lead scientist for unshackling your AI program—but tomorrow he’s going to have a job somewhere else.

Page 161 — The matrix blurred and phased as the Flatline executed an intricate series of jumps with a speed and accuracy that made Case wince with envy. “Shit, Dixie. . . .” “Hey, boy, I was that good when I was alive. You ain’t seen nothin’. No hands!”

This bit hits home with me—as I feel that way about Gibson’s writing as opposed to my own writing. At his best, he makes me wince with envy. But I don’t get stuck on that place. I know I can do cool stuff too. In the end it’s not so much envy as it is admiration, and sense of happiness that I know a guy like this, and that we’re both on the same side.

Page 164 — This is memory, right? I tap you, sort it out, and feed it back in.” “I don’t have this good a memory,” Case said, looking around. He looked down at his hands, turning them over. He tried to remember what the lines on his palms were like, but couldn’t. “Everybody does,” the Finn said, dropping his cigarette and grinding it out under his heel, “but not many of you can access it. Artists can, mostly, if they’re any good.”

Really love this. I do happen to have a very good memory, and old college friends might say, “I don’t remember that at all. How do you do it?” And I’d agree with Gibson’s notion that they do really have all those memories—I mean why wouldn’t they, as our brains are pretty much the same, and memory is pretty much a standard biochemical thing. But not all of us have the will to push hard enough to get at those old memories. One thing a therapist might do for you is to help you push. But if you’re an artist or an author, you tend to do the pushing on your own.

I’m not the most outgoing and sociable person, and people at a party might think I’m out of it, just staring, and not contributing. But I know that inside my head the holoscanner is running, and everything is being permanently recorded. Jack Kerouac was known among his friends for being like that. Memory Babe.

Page 178 — Bad timing, really, with 8Jean down in Melbourne and only our sweet 3Jane minding the store.

That name 3Jane really cracks me up. Such a simple move on Gibson’s part, but so effective. And we’ve got an 8Jane too!

Page 183 — Brain’s got no nerves in it, he told himself, it can’t really feel this bad.

Good observation to someone with a severe hangover, or heavily coming down from a heavy trip. Once a fan mailed me some camote underground fungus, and I was idiot enough to eat it, and was really at the bottom of the sea in the morning. Sylvia got me out on the porch and I lay back on a chaise-longue, and she brightly said, “Nap time!”

Page 231 — Something he’d found and lost so many times. It belonged, he knew— he remembered— as she pulled him down, to the meat, the flesh the cowboys mocked. It was a vast thing, beyond knowing, a sea of information coded in spiral and pheromone, infinite intricacy that only the body, in its strong blind way, could ever read.

Sex vs cyber thrills, yes. Over and over we have to remind ourselves that it’s not all about head trips, and screens, and sense-stim. The physical world is so much richer than our simulations. And biology is so gnarly and devious. I mean, come on, this shit evolved in parallel on the entire surface of the earth, with updates every nanosecond, for millions of years. You’re not going to get there by running a room-sized Google computer for a day.

Page 232 — She shuddered against him as the stick caught fire, a leaping flare that threw their locked shadows across the bunker wall.

Here again, that thing about the richness of the real world. Shadows. Flames. Yah, mon.

Page 233 — He looked at the backs of his hands, saw faint neon molecules crawling beneath the skin, ordered by the unknowable code. He raised his right hand and moved it experimentally. It left a faint, fading trail of strobed afterimages.

Now this has got to be an acid experience. Transreal, baby. I really had only one totally massive acid trip in my life, in a grad-student apartment with wife Sylvia in New Jersey on Memorial Day 1970, with baby Georgia already on the scene, I was feeding her mush in the kitchen, and I saw exactly what Bill’s talking about. All the normal image preprocessing and postprocessing was offline. I was seeing images with a warped meat eyeball. The capillaries beneath the skin. The biological code unknowable, yes. And those normally-ignored trails coming off a moving hand. A good time? Well, not exactly. But memorable indeed.

Page 248 — His eyes were eggs of unstable crystal, vibrating with a frequency whose name was rain and the sound of trains, suddenly sprouting a humming forest of hair-fine glass spines.

Rock it, Bill! “Whose name was ran and sound of trains.” Doesn’t get any better than that.

Page 249 — His vision was spherical, as though a single retina lined the inner surface of a globe that contained all things, if all things could be counted.

The poet attains the mathematical mode of four-dimensional vision. Seeing it all, inside and out. Nothing hidden from the Eye of God.

Count Zero

Location 369 — the condos of Barrytown crested back in their concrete wave to break against the darker towers of the Projects. That condo wave bristled with a fine insect fur of antennas and chicken-wired dishes, strung with lines of drying clothes.

Another loser-type hero to root for. In Jersey, natch. This image of the “insect fur of antennas” is very strong. Bill pays attention to what he sees. And the clash between “insect” and “fur,” so lovely. Like two dissonant notes in chord. Yes, the antennas are like fur because they’re tiny projections that grow out into the silhouette. And they’re insectile because they’re still and robotic and in some sense evil. Is there a band called “Insect Fur”? Should be.

Location 385 — Then his head exploded. He saw it very clearly, from somewhere far away. Like a phosphorus grenade. White. Light.

White light is of course a phrase I love: I used to for the title of my first novel, which was, to some extent, inspired by LSD. Just like Neuromancer. Cyberpunks, man. Acid is the only answer. Showed us the deep meaning of the impending software wetware tsunami wave. Bill’s got that 4D god-eye thing going here too.

Location 398 — As the sound faded, Turner heard the cries of gulls and the slap and slide of the Pacific.

So beautiful. Key move for good fiction: filling in sensory input. Sight, sound, touch…as much as you can, but without overdoing it. Slap and slide is just what the water does.

Location 658 — Moths strobed crooked orbits around the halogen tube.

More haiku. The “crooked” is key. And the strobe of the rapidly flickering light. Bill pays attention.

Location 2132 — He slowly shook his narrow, strangely elongated head.

This line might some from a letter or remark I made to Bill in the early 1980s. His head really is kind of long and thin, and, I used to claim, maybe even flexible. I was working on my novel Wetware, although initially I thought it was a short story called “People That Melt.” And I tried to get Bill to collaborate on it with me, and he didn’t want to, but he did write me a page or two of stuff I could use. And I think that when he wrote me, he mentioned that he was “nodding my narrow, strangely elongated head.”

Feeling that Gibson was now part of the flow, I put in a thin-headed character called Max Yukawa. I haven’t read Wetware for a while, but I seem to remember that Max Yukawa was a drug supplier; in particular he made a substance called merge. You and a partner would get into a kind of hot tub, a “love puddle,” and you’d add merge to the water, and your bodies would melt for a while, all the curled up proteins relaxing and stretching out, you two would be a blob with your four eyes floating on top. It felt good. My character Darla and her husband Whitey Mydol liked to do it.

Wetware was the most cyberpunk book that I—or anyone else—ever wrote. In my opinion.

Location 2148 — There’s things out there. Ghosts, voices. Why not? Oceans had mermaids, all that shit, and we had a sea of silicon, see? Sure, it’s just a tailored hallucination we all agreed to have, cyberspace, but anybody who jacks in knows, fucking knows it’s a whole universe. And every year it gets a little more crowded, sounds like . . .

Location 2154 — Ten years ago, if you went in the Gentleman Loser and tried telling any of the top jocks you talked with ghosts in the matrix, they’d have figured you were crazy.

I think this is a really interesting idea. What if autonomous, self-perpetuating patterns did take form in our internet. Lots to think about.

Location 2433 — He handed Rudy the bottle. “Stay straight for me, Rudy. You get scared, you drink too much.

Here we get to a part of Count Zera that’s weird for me. In SF fan-argon, you might say that Bill “Tuckerizes” me and perhaps my wife Sylvia, that is, bases characters on us. The POV character Turner goes to visit his older brother Rudy in an old country house, not unsimilar my then-house in Lynchburg, Virginia, where Bill visited us. And the Rudy character is a hopeless alcoholic

Years ago, Bill denied to me that this Rudy was an image of me, but in recent years he okay, it was. He and said it was because he was in some sense wary of me back then, and worried about ending up like how he imagined me to be, based on the samplings of my behaviors that he’d seen, me always drunk as a skunk at SF cons.

Oh well. From my old-man-now vantage point, I appreciate his elegiac sympathy for the old Rudy, his sorrow and pity, and I’m glad that I got well.

But wait, the kicker is that Turner sleeps with Rudy’s wife! And let’s be clear, I’m not saying this is something that happened or even came near to happening in real life, Bill was only at our house for a few hours. The seduction episode is just a writer’s fantasy— but it does remind me of Sylvia.

Location 2450 — “Tongues,” Sally said, Rudy’s woman, from the creaking rattan chair, her cigarette a red eye in the dark. “Talking in the tongues.” . . . The coal of the cigarette arced out over the railing and fell on the gravel that covered the yard.

Turner was aware of the length of her tanned legs, the smell and summer heat of her, close to his face. She put her hands on his shoulders. His eyes were level with the band of brown belly where her shorts rode low, her navel a soft shadow . . . He thought she swayed slightly, but he wasn’t sure. “Turner,” she said, “sometimes bein’ here with him, it’s like bein’ here alone . . .”

So he stood, rattle of the old swing chain where the eyebolts were screwed deep in the tongue and groove of the porch roof, bolts his father might have turned forty years before, and kissed her mouth as it opened, cut loose in time by talk and the fireflies and the subliminal triggers of memory, so that it seemed to him, as he ran his palms up the warmth of her bare back, beneath the white T-shirt, that the people in his life weren’t beads strung on a wire of sequence, but clustered like quanta, so that he knew her as well as he’d known Rudy… “Hey,” she whispered, working her mouth free, “you come upstairs now.”

As I say, maybe the wife isn’t modeled on Sylvia at all, and maybe I’m just thinking this way because I miss her so much, and I see her everywhere. But it’s nice to think about her. Like coming across a dear one’s touching photo, tucked into an old book.

Moving on now.

Location 3250 — “His head,” she said, her voice shaking, “his head . . .” “That was the laser,” Turner said, steering back up the service road. The rain was thinning, nearly gone. “Steam. The brain vaporizes and the skull blows . . .

This isn’t Rudy’s head we’re talking about, thank god, it’s some bad guy who ambushed Turner, and Turner’s crew took down the baddie. Kind of cool way to die. Exploding head! Why aren’t all of Bill’s books movies? And mine too?

Location 3572 —…the damp-swollen cardboard covers of black plastic audio disks beside battered prosthetic limbs trailing crude nerve-jacks, a dusty glass fishbowl filled with oblong steel dog tags, rubber-banded stacks of faded postcards, cheap Indo trodes still sealed in wholesaler’s plastic, mismatched ceramic salt-and-pepper sets, a golf club with a peeling leather grip, Swiss army knives with missing blades, a dented tin wastebasket lithographed with the face of a president whose name Turner could almost remember. . .

Jorge Luis Borges, William Burroughs, and Thomas Pynchon are key influences on the cyberpunk writers. Borges liked to do a routine of writing incredibly recondite and non-linear lists, and I think all of us have tried emulating him. Bill does a nice job here.

I wonder if ChatGPTs would be any good at generating Borges lists. Probably not yet. Not deep enough.

Location 3609 — Turner snapped the biosoft back into his socket. This time, when it was over, he said nothing at all. He put his arm back around Angie and smiled, seeing the smile in the window. It was a feral smile; it belonged to the edge.

The constant refrain and undertone of how far-out and weird the cyberpunk characters are.

Location 3636 — Uncounted living spaces carved out of the shells of commercial buildings that dated from a day when commerce had required clerical workers to be present physically at a central location.

Another correct future vision. This is exactly what’s happing to many of our big cities, San Francisco in particular, given that techie work lends itself so well to remote collaboration.

Location 3828 — She managed to get her boot back into the purse, then twisted herself into her jacket. “That’s a nice piece of hide,” Jones said.

I just love that last phrase. “a nice piece of hide.” I’m laying in wait now, hoping for a chance to use it. The flatness of the expression, the simplicity, it’s writing degree zero, language with a flat tire.

Location 3856 — Eyes wide, Marly watched the uncounted things swing past. A yellowing kid glove, the faceted crystal stopper from some vial of vanished perfume, an armless doll with a face of French porcelain, a fat, gold-fitted black fountain pen, rectangular segments of perf board, the crumpled red and green snake of a silk cravat . . . Endless, the slow swarm, the spinning things . . .

The closing scene of Count Zero. Bill has this obsession with the artist Joseph Cornell’s boxes: assemblages of objects displayed together in a shadow box case. And here we have the ultimate Cornell, a flock of objects bobbing and weaving in zero gravity. Also it’s a Borges-style list. “Endless, the slow swarm, the spinning things.” Wonderful.

Mona Lisa Overdrive

Page 116 — It was what Eddy called an art crowd, people who had some money and dressed sort of like they didn’t, except their clothes fit right and you knew they’d bought them new.

But exactly. The jeans with big holes in them? These days you take it further, and the clothes don’t fit right. My granddaughter wears jeans with a 47 inch waist, and uses a mouse cable for a belt. I’m more out of it all the time.

Page 126 — Becker explored the planes of her face in a tortured, extended fugue, the movement of his images in exquisite counterpoise with the sinuous line of feedback that curved and whipped through the shifting static levels of his soundtrack.

He’s describing a film, or rather a sim that you watch with electrodes. What catches my eye here is the “sinuous line of feedback.” I don’t like automatic music that repeats, like while you’re on hold on a phone. As a commutation, it’s really not hard to get something gnarlier. Feedback!

Page 225 — There wasn’t anything random about the Judge and the others. The process was random, but the results had to conform to something inside, something he couldn’t touch directly.

In this part of the book there’s a guy called Slick Henry who’s a little like the California artist Mark Pauline a great hero of cyberpunks. I heard about him from Marc Laidlaw and Richard Kadrey when we moved to San Jose in 1986. Pauline cobbles together one-of-a-kind machines that incorporate flame throwers, giant pincers, and the like. They’re not exactly robots; Pauline operates them using remote controls. Slick Henry’s best machine is called the Judge, and is also operated by a remote.

251—The man with the bullhorn came strolling out of the dark with a calculated looseness meant to indicate that he was on top of things. He wore insulated camo overalls with a thin nylon hood drawn up tight around his head, goggles. He raised the bullhorn. “Three minutes.”

The mercenaries are attacking the good guys who are holed up in abandoned factory. I’ve always hated voiced from bullhorns…so bullying. Good touch here, to help urn you against them.

Our guys are gonna send out one of Slick Henry’s machines to fight them off. The Judge. For some reason Slick Henry can’t run the controls, so his friend Gentry is doing it.

253—The Judge was well back, out of the light, visible only because it was moving, when Gentry discovered the combination of switches that activated the flamethrower, its nozzle mounted beneath the juncture of the claws.

Slick watched, fascinated, as the Investigator ignited ten liters of detergent-laced gasoline, a sustained high-pressure spray. He’d gotten that nozzle, he remembered, off a pesticide tractor.

It worked okay.

Love the understatement, “It worked okay.” I remember Marc Laidlaw and Sylivia and I going to a Marc Pauline under a freeway overpass in San Francisco. It was so awesome the machines stacked up a couple of grand pianos and set them on fire.

256—In the hard wind of images, Angie watches the evolution of machine intelligence: stone circles, clocks, steam-driven looms, a clicking brass forest of pawls and escapements, vacuum caught in blown glass, electronic hearthglow through hairfine filaments, vast arrays of tubes and switches, decoding messages encrypted by other machines.… The fragile, short-lived tubes compact themselves, become transistors; circuits integrate, compact themselves into silicon.… Silicon approaches certain functional limits

A history of computation in a nutshell here. Leading up to biocomputation, a new frontier that we’re still just nibbling at. It’s definitely a theme in the Sprawl trilogy.

276—The world hadn’t ever had so many moving parts or so few labels.

We’re in Mona’s point of view now. She’s feeling out of her depth, surrounded by ten or twenty other characters, all of them weird and willful with intricate personal agendas. Like the reader, at this point. In a minute or two Mona will get high on wiz. See the next excerpt.

282—And it was the still center again. Just like that time before.

So fast it was standing still.

Rapture. Rapture’s coming.

So fast, so still, she could put a sequence to what happened next: This big laugh, haha, like it wasn’t really a laugh. Through a loudspeaker. Past the door. From out on the catwalk thing. And Molly just turns, smooth as silk, quick but like there’s no hurry in it, and the little gun snicks like a lighter.

Then there’s this blue flash outside, and the big guy gets sprayed with blood from out there as old metal tears loose and Cherry’s screaming before the catwalk thing hits with this big complicated sound, dark floor down there where she found the wiz in its bloody bag.

“Gentry,” someone says, and she sees it’s a little vid on the table, young guy’s face on it, “jack Slick’s control unit now. They’re in the building.” Guy with the Fighting Fish scrambles up and starts to do things with wires and consoles. And Mona could just watch, because she was so still, and it was all interesting stuff.

How the big guy gives this bellow and rushes over, shouting how they’re his, they’re his. How the face on the screen says: “Slick, c’mon, you don’t need ’em anymore.…”

Then this engine starts up, somewhere downstairs, and Mona hears this clanking and rattling, and then somebody yelling, down there.

And sun’s coming in the tall, skinny window now, so she moves over there for a look. And there’s something out there, kind of a truck or hover, only it’s buried under this pile of what looks like refrigerators, brand-new refrigerators, and broken hunks of plastic crates, and there’s somebody in a camo suit, lying down with his face in the snow, and out past that there’s another hover looks like it’s all burned up.

It’s interesting.

Nice drug rush, the way Mona is watching everything with total detachment. It’s interesting. They had a friend drop an airborne container-truck’s worth of kitchen appliances on the bad guys. At this point the book’s almost over, and all of the many characters are racing around doing stuff and explaining things. Kind of like the end of a Raymond Chandler novel where all the threads are being braided together.

300—“You want this hover?” Sally asked. They were maybe ten kilos from Factory now and he hadn’t looked back.

“You steal it?”

“Sure.”

“I’ll pass.”

“Yeah?”

“I did time, car theft.”

“So how’s your girlfriend?”

“Asleep. She’s not my girlfriend.”

“No?”

“I get to ask who you are?”

“A businesswoman.”

“What business?”

“Hard to say.”

So here’s Sally Shears (formerly known as Molly Millions) driving off in a hovercraft and talking with Slick Henry. Cherry Chesterfield is in back. Vintage Gibson conversation, utterly minimalist and hip. We’re done! All’s well that ends well.

What a ride.

Thanks, Bill.