I got an emailed question about my novel Spacetime Donuts from a fan of mine, who prefers to be known as Skinner Darkly. I said, hell, let’s make it an online interview, haven’t done one of those for a couple of months. So here you are. I’m publishing it here, and on Medium. This time around, all but two of the illos are recent paintings by me. Most of them are for sale. See info about them on my Paintings Page

The overall theme? Well, seems like in a lot of the answers I’m bitching about the woes of an aging writer’s life. Oh god, am I turning into that guy? Well there’s some stories and jokes too, also those nice paintings.

Q1. You’re very open about using real people as springboards for your characters, are the characters in Juicy Ghosts inspired by anyone, or were they created whole cloth for the occasion?

A1. My friends and family got tired of me writing about them, so In recent years I’ve gotten better at inventing characters, or at collaging them together from pieces of the people I know. Another move to lighten the load on my family and friends is to base characters on people I don’t actually know very well. I might just pick up something about their appearance or their way of talking. Like sketching from life. But of course the Ross Treadle character in Juicy Ghosts is strongly based on Donald Trump. Keep in mind that I wrote and published this novel shortly before the 2020 Presidential election, and I was hoping that my work might help, in some small way, to turn the tide. Ross Treadle actually gets killed three times in the novel: flesh, clone, and software emulation. Feels so good that once isn’t enough.

Q2. In Juicy Ghosts, as well as Mathematicians In Love, you use music as a kind of bridge to explain/solve complex problems for the characters. Does this reflect your own feelings about music and its place in the world?

A2. That’s an interesting question. Being a mathematician and a computer scientist, I often want to bring highly abstract ideas into my stories. Like if, for instance, I’m talking about an algorithm that creates a self-perpetuating model of someone’s mind—or I’m talking about a tech design for actual telepathy. And here music and art can come in.

Music is indeed an alternate language system that we’re all familiar with. Music often seems to be saying things that we can’t concisely put into words. And music digs into the emotions more easily than words. The insistent force of music is striking.

At times I turn to visual art rather than to music. In Mathematicians in Love, I described a Berkeley grad student’s doctoral thesis in terms of illustrations lifted from Dr. Seuss’s The Cat in the Hat. Those images have some of the same mad playfulness that you find in higher math.

Q3. Still on the topic of music, despite having a brief stint as the front man of a punk band, I’ve seen very little discussion about your specific tastes. Who are some of the musicians you return to most often, for fun or focus?

A3. Front man of a punk band? Yes, that would be The Dead Pigs, an integral part of my farewell to employment at Randolph-Macon Woman’s College. You can see two videos of us here, along with the background story.

[The old man nods off in euphoric recollection.]

Snort—what? Taste in music, yes. First let me make clear that I never listen to music while I write. Silence is best. I like to hear the rhythms of the words in my head. Writing prose isn’t so far from poetry.

But who I like? Certainly the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Frank Zappa, the Ramones, Lou Reed, Blondie, Hole, L7, the Breeders, Nirvana, the Pixies, the Clash, Dylan, Neil Young, Little Feat, Muddy Waters, Robber Johnson, Charles Mingus, Oasis, Elvis, Flatt & Scruggs, Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, Mozart’s Magic Flute, Rancid, NOFX, The Jesus and Mary Chain, Iggy, the Stooges, Green Day, Velvet Underground, Weezer, The Police, Talking Heads, Jefferson Airplane, Beach Boys, Bo Diddley, Beck, John Coltrane, Jimi Hendrix, Bob Marley, Linton Kwesi Johnson, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Dead Kennedys, Patti Smith, Junior Murvin, Jimmy Cliff, and Washer Drop.

I could tell you stories about listening to songs by every one of these artists—had we but world enough and time. For instance: Paul Simon’s “Graceland” was one of Sylvia’s very favorite songs. And the kids and I played it for her one last time, right after she died.

Q4. Going back to your first novel, Spacetime Donuts, you don’t often talk about it in a creative context. With an entire careers worth of hindsight, what do you feel its place is in the Rudy Rucker Canon?

A4. Spacetime Donuts was the one that helped me get going. I had no idea how to write a novel, but I did have an electric typewriter. I started writing a story, and kept going with it, putting in chapter breaks to catch my breath. As is still my habit, I didn’t really plan the story, I made it up as I went along. Like talking aloud. And, there were a couple of particular ideas I wanted to get to.

One was the notion of circular scale, that is, the idea that if you shrink long enough you’ll get to a level that looks very much like our own. This is a fairly common idea. I think I first encountered it in the movie The Incredible Shrinking Man, which I saw with a bunch of my friends on my twelfth birthday—to lasting effect. My twist on this trope was that the seemingly familiar level way down there would in fact be very same size level you started from.

Another idea inspiring the novel was the proto-cyberpunk notion that there could be a society-spanning computer system that was running things and making life more boring.

Q5. You lived in Llynchburg, Virginia, for a while, yes? I’m not to far from there now. Do you have any musings on your time in the area?

A5. Yes indeed, Lynchburg from 1980 to 1986. Home town of the evangelist Jerry Falwell, oddly enough. And this very hamlet was fated to be a cradle of cyberpunk.

I worked as a math professor at Randolph-Macon Woman’s College for two years, and then they fired me—no special reason, they just didn’t like my attitude. Of course not! And then I became a freelance writer for four years. Tough row to hoe. I rented a room in an abandoned, tumbledown house that had been the offices of some friends. The Design Group.

Our family had a nice big house, and I think it was a happy period in our three kids lives. We had a good social life—that’s a thing about living in a really small town. Sylvia found a sign-painting job, and then a teaching job. But she wasn’t all that glad to be in a small, Southern town.

Was I happy? Yes and no. On the down side, I’d lost my job, and I was worried about how much I drank and got high. Sometimes I was behaving badly, and I felt guilty about that. And we were poor.

On the upside, as far as the writing went, I was living the dream. Dark fun with black flames flickering over everything. It was the most productive period my life. I wrote and sold six books in four years. I was out of control.

I look at someone like Vincent van Gogh or David Foster Wallace, and I wonder how you could kill yourself at the very peak of your career. But when I remember Lynchburg, I understand.

If you’re out on the creative edge day after day for years, you push yourself too far. You’re never satisfied. Every finish line sets up a new start. I was loving it, and proud of my writing, but I was ready to snap.

And then a miracle job came through. I morphed into a professor of computer science at San Jose State in Silicon Valley. A salary, insurance, and a new crowd of friends. And a chance to learn computer science on the fly. Yeah, baby. They know how to treat cyberpunks in California!

Sylvia became a professor of English as a Second Language out here. She was an extremely good teacher. Eventually she had a higher salary than me.

Q6. You’ve written several queer main characters in your career, including an entire SF romance novel, Turing & Burroughs. Do you have a different approach to writing queer romances vs. Straight ones? What about having real people underlying the characters of Turing & Burroughs, as opposed to using the invented characters Liv and Molly in Juicy Ghosts?

A6. I grew up in Louisville, Kentucky, in the 1950s. and I was heir to a certain amount of homophobia. I barely even know what queers were, but I knew I didn’t want to be one. I was scared of them. But when I was about fifteen, I got hold of the Beat author William Burroughs’s Naked Lunch. I loved his contempt for all social norms. He made being a queer junkie seem cool—and funny. Funny from the inside, you understand. Not like the squares, frowning from the outside.

Alan Turing was another famous gay man that I latched on to. He was amazingly out. If he met a man that interested him, he’d ask the man for sex straight up. Describing this, he said something like, “Either I’ll be thrown out, or I’ll have an interesting evening.”

When I started work on my gay romance novel, I wasn’t sure I could write it. I worried I wouldn’t be able to totally put myself into the mindset of being queer. But I read the massive Andy Warhol Diarys, and that was big help.

Just like other people, as they say. Except you’re an outsider. Burroughs’s writing was a great model, as was Turing’s personality. Sure I could write gay. In your face, squares!

My agent sent the manuscript for Turing & Burroughs to a number of people, and they all said, “This is well written, but we don’t want it.” In my sad enthusiasm, I’d dreamed that it might come out as a mainstream bestseller, rather than SF. And in the end, I had to fucking self-publish my masterpiece in 2012. But in 2019 Night Shade books picked it up.

I still don’t understand why the regular publishers didn’t jump at my book. Was it too outrageous? Lesser authors write things that middlebrow reviewers contentedly call outrageous. But when Rucker goes there, it’s always too far!

Another thought here is that sometimes a book about homosexual romance takes on a lugubrious tone. As if you’re writing about unfortunate souls who have cancer. This tone might even be viewed as the expected thing. But my Burroughs and Turing were having a good time. Too good, I suppose. Maybe their merriment annoyed the publishers.

As for Liv and Molly in Juicy Ghosts, I’m not fully confident that I got their romance right. Yes, as I already said, it’s just a matter of writing about a love affair, which I know how to do. And I certainly know how it feels to be an outsider. But here I didn’t have the inspiring Burroughs and Turing personas to work with. So I hope Liv and Molly worked.

Q7. Earlier this year, you said Juicy Ghosts is probably your last book, as your primary output has shifted to painting. Do you have any reflections on your experience with the publishing industry?

A7. There’s a certain arc to most writers’ careers. When you’re starting out, and if you’re a good writer, the publishers are interested in your books. Your novels are like lottery tickets for them. Possible best-sellers. And then the numbers game sets in.

Depending how your books sell over the years, it gets harder or easier to place them. An author does what they can, altering their themes, and looking for new outlets. There’s nothing more valuable than a sympathetic editor—and at any given time you only need one of them, but it’s much safer to have two or three.

For me, those magical benefactors were David Hartwell, John Oakes, Jeremy Lassen, and Cory Allyn. But then, sadly, Hartwell died, Oakes got into a different branch of publishing, and Lassen and Allyn lost their jobs. And now my books are close to being commercially unpublishable. Even though my recent novels have been as good or better any I wrote before.

I don’t like to dwell on this—I don’t want to be that guy, the old man who’s totally lost it and can’t sell a book. I mean there are workarounds. I know how to do Kickstarter, design my own books, and self-pub them for distribution in print and ebook via Amazon and the other online booksellers—all like that.

Well, what about publicity? All you’ve got is the social networks. I’ve gotten skilled at those short messages formerly known as tweets. Clever ideas, snarky griping, haiku-like apercus, crystalline photos, images from the gone world. I enjoy creating them. It’s a form of art.

What else? Well I’ve put most of my books online to read for free as web pages. The main thing is to keep the stuff bouncing. Build the brand. Sell merch.

Am I glad my writing is still out there and being read? Of course. Am I bitter about having to distribute so much of it myself? What do you think!

Faint gleams of light. Now and then a real publisher picks up one of my self-pub books and reissues it. And there’s always that tyro dream of posthumous fame. I don’t go for that dream like I used to. Having known a lot of people who died, the posthumous thing doesn’t work for me anymore.

Hey, it’s enough that you’re reading me right now. Even though I’m not getting paid. It’s enough that my mind viruses are infecting you in realtime. And thereby making this a better world.

Q8. In the late 90’s to early 2000’s you talked a lot about how wider availability would make the internet a truly democratic place. Twenty years later and now most of what we see is controlled by a mega corporations and their complex algorithms, do you think that there’s still hope for a truly democratic cyberspace?

A8. The loss of control is an illusion. Believing it’s happened is just a way of being passive and lazy or even cowardly. The free, democratic cyberspace is still there. It never went away. You have free rein.

Sure, you can’t always post whatever you want in some commercial walled garden like Facebook. But you don’t have to spend all your time there. Also, most commercial sites really don’t give a fuck what someone like you or me would post. The only censorship I’ve encountered in all these years was when Apple asked me to paint a bikini onto the cover-image alien of my political SF novel The Sex Sphere.

And remember, it’s quite easy to create your own website. Get a webpage on an independent webhost, register a domain name for your page, and post whatever the hell you want. You have free rein. There are absolutely no barriers to setting up a webpage and posting whatever you want.

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again. The freedom of the web is one of the great blessings of modern times. The web got loose before the Pig had a chance to lock it down. And they’ll never ever take control of it. Even if they tried, they wouldn’t be able to. Because we’re everywhere.

Q9. Lastly, different creative outputs often scratch different itches; what drew you to, and what do you enjoy about the medium of painting? Do you find a different kind of fulfillment compared to writing?

A9. (For this final answer, I’m going to draw on an interview Robert Penner did with me for his excellent ezine Big Echo, now sadly extinct.)

There is a certain commonality between my writing and painting. I think it’s the attitude that’s the important thing. The specific ideas—well, I always just think about the same few things, whatever I’m doing. Sex, gnarl, color, sounds, and the Now. I’m here in this rich, amazing reality and—I can’t believe it!

My family teases me. “Be quiet, Rudy. You always say that. You can’t believe anything.”

So, okay, I have no mind. It’s my attitude that’s the key. What kind of attitude is needed in order to write, or paint, or take photos?

Be loose. Spontaneous bop prosody. Forget yourself. As I say, Keep it bouncing. Ruin it, fix it, ruin it again. Make it fun. Revise, revise, revise. God is in the details.

Painting has made some of these practices clearer to me. Like the whole concept of painting over an awkward patch—yeah. And the importance of popping the colors and working the chiaroscuro.

If I’m painting to match a sketch, it’s a drag, and it doesn’t really work. It’s better when I’m mindlessly dabbling, just following the shapes and the colors, and letting my brush loose. Ditto for writing. I don’t worry too much about outlines. I prefer surprise. If the action takes over, and the characters are talking, and I’m dreaming while I’m awake, and transcribing what I see—that’s when it’s good. I’m in it so deep that I’m gone.

I feel like I’m morphing into a painter. I took up painting in 1999 while writing my historical novel As Above, So Below about the Flemish master Peter Bruegel the Elder. I wanted to see how painting felt, and I quickly came to love it.

I enjoy the exploratory and non-digital nature of painting, and the luscious mixing of the colors. Sometimes I have a specific scenario in mind. Other times I don’t think very much about what I’m doing. I just paint and see what comes out. Working on a painting has a mindless quality that I like. The words go away, and my head is empty. And I can finish a painting in less than a week.

I’ve done about 260 paintings by now, and I’m steadily getting better. I like making them, and I’m doing okay with selling them online, in fact these days I make more money from my paintings than I do from my new writing.

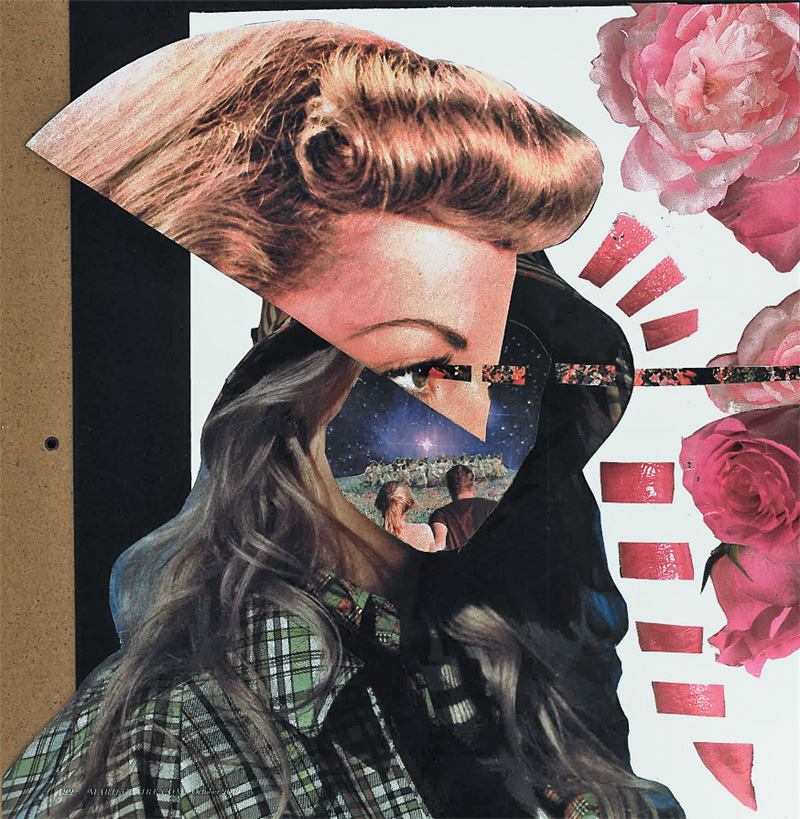

And now, in closing, here’s Feminen Mistique, a work by my interviewer, Skinner Darkly. Thanks, friend. Fun interview!