I just spent a couple of weeks rereading John Updike’s Rabbit Qunitet, that is the four novees Rabbit Run, Rabbit Redux, Rabbit is Rich and Rabbit is Rest, plus a final novelette, “Rabbit Remembered.” The five works appeared, approcimitely, in 1960, 1970,1980, 1990, and 2000.

Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom is the hero. A one-time high-school basketball star, aging through the decades. Marriage problems, family problems, puzzling about the meaning of life, taking joy from the world’s details. Viewed from 2020, Rabbit’s thoughts about women are occasionally questionable. But one keeps in mind that he’s a character of his times, and is not necessarily Updike himself.

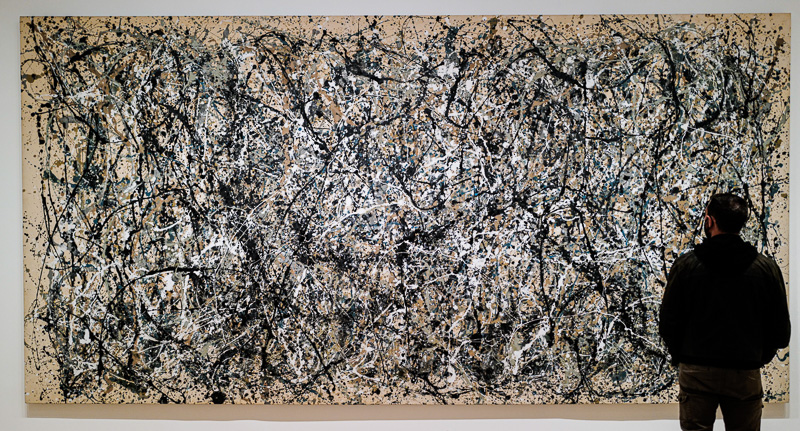

I read the quintet on Kindle, and highlighted passages that I liked, so for today’s post, I’m interleaving the quotes with some photos, mostly froum our recent trip to New York City, mostly taken with my new camera.

I think (but don’t gurantee) that the numbers by the excerpts match the page numbers in the printed book. And as always, the images have no calculated connetions with the texts, but the universal quantum wave function called Surrealism will ensure harmonies.

One more thing, mostly the main character is referred to as “Rabbit,” but often Updike uses his given name “Harry.”

—–Begin excerpts from Rabbit Run by John Updike—–

10. Priest: “God gives to each one of us a special talent.”

Janice and Rabbit become unnaturally still; both are Christians. God’s name makes them feel guilty.

16. At the corner, where Wilbur Street meets Potter Avenue, a mailbox stands leaning in twilight on its concrete post. Tall two-petaled street sign, the cleat-gouged trunk of the telephone pole holding its insulators against the sky, fire hydrant like a golden bush: a grove. He used to love to climb the poles. To shinny up from a friend’s shoulders until the ladder of spikes came to your hands, to get up to where you could hear the wires sing. Their song was a terrifying motionless whisper. It always tempted you to fall. The insulators giant blue eggs in a windy nest.

60. (Meeting is soon-to-be-mistress Ruth.) Rabbit sits down too and feels her rustle beside him, settling in, the way women do, fussily, as if making a nest. … He pulls his head back and slumps slightly, to look down past the table edge, into the submarine twilight where her foreshortened calves hang like tan fish. They dart back under the seat. … He stands up and takes her little soft coat and holds it for her, and like a great green fish, his prize, she heaves across and up out of the booth and coldly lets herself be fitted into it.

76. (Rabbit overhears the punchline to an unknown joke.) “But man, mine was helium!”

93. As if to seek the entrance to another dream he reaches for her naked body across the little distance and wanders up and down broad slopes, warm like freshly baked cake

.

95. (Rabbit presses Ruth.)

“Why don’t you believe anything?”

“You’re kidding.”

“No. Doesn’t it ever, at least for a second, seem obvious to you?”

“God, you mean? No. It seems obvious just the other way. All the time.”

“Well now if God doesn’t exist, why does anything?”

“Why? There’s no why to it. Things just are.”

114. She is tepid and solid in his embrace, not friendly, not not.

133. You know how it is with fathers, you never escape the idea that maybe after all they’re right.

142. (Rabbit takes a job as a gardener.)

Sun and moon, sun and moon, time goes. In Mrs. Smith’s acres, crocuses break the crust. Daffodils and narcissi unpack their trumpets. … He loves folding the hoed ridge of crumbs of soil over the seeds. Sealed, they cease to be his. The simplicity. Getting rid of something by giving it to itself. God Himself folded into the tiny adamant structure, Self-destined to a succession of explosions, the great slow gathering out of water and air and silicon: this is felt without words in the turn of the round hoe-handle in his palms.

149. (Rabbit at the pool with Ruth.)

Her bottom of its own buoyance floated up and broke the surface, a round black island glistening there, a clear image suddenly in the water wavering like a blooey television set: the solid sight swelled his heart with pride, made him harden all over with a chill clench of ownership.

171. She yanks powerfully at the lever of the ice-cube tray and with a brilliant multiple crunch that sends chips sparkling the cubes come loose.

176. He drives past a corner where someone is practicing on a trumpet behind an open upstairs window. Du du do do da da dee. Dee dee da da do do du.

237. The fullness ends when we give Nature her ransom, when we make children for her. Then she is through with us, and we become, first inside, and then outside, junk. Flower stalks.

238. Your wife’s parents can’t get at you the way your own can. They remain on the outside, no matter how hard they knock, and there’s something relaxing and even comic about them.

—–Begin excerpts from Rabbit Redux by John Updike—–

57. A car moves on the curved road outside. Rugs of light are hurled across the ceiling.

75. Sex ages us. Priests are boyish, spinsters stay black-haired until after fifty. We others, the demon rots us out.

[My agent, John Silbersack.]

124. (Radical Black guy Skeeter who will settle in at Rabbit’s house after Janice leaves. From his first, self-introductory rant.)

“All these Charlies is heartbreakers, right? Just cause they don’t know how to shake their butterball asses don’t mean they don’t get Number One in, they gets it in real mean, right? The reason they so mean, they has so much religion, right? That big white God go tells ’em, Screw that Black chick, and they really wangs away ’cause God’s right there slappin’ away at their butterball asses. Cracker spelled backwards is f*cker, right?”

Rabbit wonders if this is how the young man really talks, wonders if there is a real way. He does not move, does not even bring back his hand from the woman’s inspection, her touches chill as teeth. He is among panthers.

131. As Babe plays she takes on swaying and leaning backwards; at her arms’ ends the standards go root back into ragtime. Rabbit sees circus tents and fireworks and farmers’ wagons and an empty sandy river running so slow the sole motion is catfish sleeping beneath the golden skin.

…Rabbit’s inside space expands to include beyond Jimbo’s the whole world with its arrowing wars and polychrome races, its continents shaped like ceiling stains, its strings of gravitational attraction attaching it to every star, its glory in space as of a blue marble swirled with clouds; everything is warm, wet, still coming to birth but himself and his home, which remains a strange dry place, dry and cold and emptily spinning in the void of Penn Villas like a cast-off space capsule.

171. “The mountain was really quite deserted.”

“Except for hawks, Dad. They sit on all these pine trees waiting for the guys to put out whole carcasses of cows and things. It’s really grungy.”

178. “Anyway, Dad, in a society where power was all to the people money wouldn’t exist anyway, you’d just be given what you need.”

“Well hell, that’s the way your life is now.”

“Yeah, but I have to beg for everything, don’t I? And I never did get a mini-bike.”

210. “Harry, it just came over the radio, engraving had it on. Kennedy’s been shot. They think in the head.” Both charmers [JFK and (remembered) FDR] dead of violent headaches. Their smiles fade in the field of stars. We grope on, under bullies and accountants.

218. “I love you,” he says, and the fact that he doesn’t makes it true.

244. It frightens him, as museums used to frighten him, when it was part of school to take trips there and to see the mummy rotting in his casket of gold,

335. She is gumdrops everywhere, yet stately as a statue, planetary in her breadth, a contour map of some snowy land where he has never been;

339. The universe is unsleeping, neither ants nor stars sleep, to die will be to be forever wide awake.

376. (Rabbit’s sister Mim’s) marvellously masked eyes force upon her pale mouth all expressiveness; each fractional smile, sardonic crimping, attentive pout, and abrupt broad laugh follows its predecessor so swiftly Harry imagines a coded tape is being fed into her head and producing, rapid as electronic images, this alphabet of expressions.

379. (Looking at his childhood home with Mim.)

Rabbit can’t remember it, he just remembers them being here together, in this house season after season, for grade after grade of school, setting off down Jackson Road in the aura of one holiday after another, Hallowe’en, Thanksgiving, Christmas, Valentine’s Day, Easter, in the odors and feel of one sports season succeeding another, football, basketball, track; and then him being out and Mim shrunk to a word in his mother’s letters; and then him coming back from the Army and finding her grown up, standing in front of the mirror, ready for boys, maybe having had a few, tinting her hair and wearing hoop earrings; and then Janice took him off; and then both of them were off and the house empty of young life; and now both of them are here again.

387. [Rabbit’s aging mother’s] laughter reminds Rabbit of the laughter of a child who laughs not with the joke but to join the laughter of others, to catch up and be human among others.

400. Time is our element, not a mistaken invader. How stupid, it has taken him thirty-six years to begin to believe that.

430.(Reunited with Janice, Rabbit and her check into a motel. The clerk calls him young.)

“I’m not so young.”

“You’re yungg,” the man absentmindedly insists, and this is so nice of him, this and handing over the key, people are so nice generally, that Janice asks Harry as he gets back into the car what he’s grinning about.

—–Begin excerpts from Rabbit is Rich by John Updike—–,

71. “(Phillies baseball player) Bowa’s being out has hurt them quite a lot,” Webb says judiciously, and pokes another cigarette into his creased face, lifting his rubbery upper lip automatically like a camel.

77. Cindy’s towel hangs on her empty chair. To be Cindy’s towel and to be sat upon by her: the thought dries Rabbit’s mouth.

84. Faces and bodies rise from the aluminum and nylon furniture (by the country club swimming pool) like the cloud of an explosion with the sound turned down on TV. More and more in middle age the world comes upon him like images on a set with one thing wrong with it, like those images the mind entertains before we go to sleep, that make sense until we look at them closely, which wakes us up with a shock.

100. The world keeps ending but new people too dumb to know it keep showing up as if the fun’s just started.

142. “I would have taken a bath,” Janice says, but she smells great, deep jungle smell, of precious rotting mulch going down and down beneath the ferns.

142. Lying spent and adrift he listens again to the rain’s sound, which now and then quickens to a metallic rhythm on the window glass, quicker than the throbbing in the iron gutter, where ropes of water twist. … Murmurously beyond their windows, yet so close they might be in the cloud of it, the beech accepts, leaf upon leaf, shelves and stairs of continuous dripping, the rain. … Rain, the last proof left to him that God exists.

203. The earth is hollow, the dead roam through caverns beneath its thin green skin.

[With my Swarthmore College friends Don Marritz and Roger Shatzkin at our hotel.]

230. Before reaching into the breast pocket of the seersucker coat, (Reverend) Campbell taps out the bowl of his pipe with a finicky calm that conveys to Harry the advantages of being queer: the world is just a gag to this guy. He walks on water; the mud of women and making babies never dirties his shoes. You got to take off your hat: nothing touches him.

263. Harry has always been curious about what it would feel like to be the Dalai Lama. A ball at the top of its arc, a leaf on the skin of a pond. A water strider in a way is what the mind is like, those dimples at the end of their legs where they don’t break the skin of the water quite.

285. (Rabbit talking to the mother of Pru, who’s about to marry his son Nelson.)

“Well, your daughter does you proud,” he tells her. “We love her already.” He sounds to himself, saying this, like an impersonator; life, just as we first thought, is playing grownup.

313. The thing about those Rotarians, if you knew them as kids you can’t stop seeing the kid in them, dressed up in fat and baldness and money like a cardboard tuxedo in a play for high-school assembly. How can you respect the world when you see it’s being run by a bunch of kids turned old? That’s the joke Rabbit always enjoys at Rotary.

327. It’s fascinating to Rabbit how long those strands of hair are [that childhood enemy Ronnie Harrison] is combing over his bald spot these days, if you pulled one the other way it would go below his ear. In this day and age why fight it? There’s a bald look, go for it. Blank and pink and curved, like an ass.

366. In these neighborhoods health-food stores have sprung up, … and little shops heavy on macramé and batik and Mexican wedding shirts and Indian silk and those drifter hats that make everybody look like the part of his head with the brain in it has been cut off.

399. At the church the people in holiday clothes are still filing in, beneath the canopy of bells calling with their iron tongues, beneath the wind-torn gray clouds of this November sky with its scattered silver.

444. Where the sea impinges on the white sand a frill of surf slowly waves, a lacy snake pinned in place. Then this flight heads over the Atlantic at an altitude from which no whitecaps can be detected in the bluish hemisphere below, and immensity becomes nothingness.

… The plane, its earnest droning without and its party mutter and tinkle within, becomes all of the world there is. … God, having shrunk in Harry’s middle years to the size of a raisin lost under the car seat, is suddenly great again, everywhere like a radiant wind. Free: the dead and the living alike have been left five miles below in the haze that has annulled the earth like breath on a mirror.

447. For years nothing happens; then everything happens. Water boils, the cactus blooms, cancer declares itself.

471. (Rabbit starting an affair with Ronnie Harrison’s wife Thelma.)

Her whole body, into her forties, has kept that trim neutral serviceability nurses and grade-school teachers surprise you with, beneath their straight faces. She laughs, and holds out her arms like a fan dancer.

“Here I am. You look shocked. You’re such a sweet prude, Harry—that’s one of the things I adore.

485. Harry suddenly hates people who seem to know; they would keep us blind to the fact that there is nothing to know. We are each of us filled with a perfect blackness.

525. Uncurtained winter light bouncing off the bare floors and blank walls turns her underwear to silver and gives her shoulders and arms a quick life as of darting fish before they disappear into an old shirt of his and a moth-eaten sweater.

533. (Rabbit’s daughter-in-law Pru) comes softly down the one step into his den and deposits into his lap what he has been waiting for. Oblong cocooned little visitor, the baby shows her profile blindly in the shuddering flashes of color jerking from the Sony, the tiny stitchless seam of the closed eyelid aslant, lips bubbled forward beneath the whorled nose as if in delicate disdain, she knows she’s good. You can feel in the curve of the cranium she’s feminine, that shows from the first day. Through all this she has pushed to be here, in his lap, his hands, a real presence hardly weighing anything but alive. Fortune’s hostage, heart’s desire, a granddaughter. His. Another nail in his coffin. His.

—–Begin excerpts from Rabbit at Restby John Updike,

100. Janice sleeps on her stomach turned away from him, and if the night is cool pulls the covers off him onto herself, and if hot dumps them on top of him, all this supposedly in her sleep.

116. There is something hot and disastrous about Nelson and Pru that scares the rest of them. Young couples give off this heat; they’re still at the heart of the world’s business, making babies. Old couples like him and Janice give off the musty smell of dead flower stalks, rotting in the vase.

128. Your children’s losing battle with time seems even sadder than your own.

133. Rabbit feels as if the human race is a vast colorful jostling bristling parade in which he is limping and falling behind.

162. (Rabbit is felled by a heart attack in the presence of his daughter-in-law Pru.)

He lies down on the sand at Pru’s feet, her long bare feet with chipped scarlet nails and their pink toe-joints like his mother’s knuckles from doing the dishes too many times. He lies face up, looking up at her white spandex crotch.

196. Maybe Nelson is right, Toyota is a dull company. Its commercials show people jumping into the air because they’re saving a nickel.

209. The magnolias and quince are in bloom, and the forsythia is out, its glad cool yellow calling from every yard like a sudden declaration of the secret sap that runs through everybody’s lives.

210. Every other house in this homely borough holds the ghost of someone he once knew who now is gone. Empty to him as seashells in a collector’s cabinet,

260. Rabbit: “Thelma? We never see her anymore, we ought to have the Harrisons over sometime.”

Janice: “Pfaa!” She spits this refusal, he has to admire her fury, the animal way it fluffs out her hair. “Over my dead body.”

Rabbit: “Just a thought.” This is not a good topic.

268. Rabbit has never gotten over the idea that the [daily] news is going to mean something to him.

304. He leans down and kisses [his nine-year-old granddaughter’s] warm dry forehead. “Don’t you worry about anything, Judy. Grandma and I will take good care of your daddy and all of you.”

“I know,” she says after a pause, letting go.

We are each of us like our little blue planet, hung in black space, upheld by nothing but our mutual reassurances, our loving lies.

310. Harry has trouble believing how his life is tied to all this mechanics—that the me that talks inside him all the time scuttles like a water-striding bug above this pond of body fluids and their slippery conduits. How could the flame of him ever have ignited out of such wet straw?

324. “Mim.” Just the syllable makes him smile. His sister. The one other survivor of that house on Jackson Road, where Mom and Pop set up their friction, their heat, their comedy, their parade of days.

350. “Harry, you’re not going to pop off,” she tells him urgently, afraid for him. That strange way women have, of really caring about somebody beyond themselves.

379. It is not night, it is late afternoon. The children, home from school, have been instructed to be quiet because Grandpa is sleeping; but they are unable to resist the spurts of squalling and of glee that come over them. Life is noise.

381. His eyelids feel heavy again; a fog within is rising up to swallow his brain. When you are sleepy an inner world smaller than a seed in sunlight expands and becomes irresistible, breaking the shell of consciousness. It is so strange; there must be some other way of being alive than all this eating and sleeping, this burning and freezing, this sun and moon. Day and night blend into each other but still are nothing the same.

398. (Rabbit unexpectedly sleeps with another woman.) Her tall pale wide-hipped nakedness in the dimmed room is lovely much as those pear trees in blossom along that block in Brewer last month were lovely, all his it had seemed, a piece of Paradise blundered upon, incredible.

436. (At the funeral of Ronnie’s wife Thelma, with whom Rabbit had that years-long affair, and Ronnie berates Rabbit.)

“I don’t give a f*ck you banged her, what kills me is you did it without giving a sh*t. She was crazy for you and you just lapped it up. You narcissistic c*cksucker. She wasted herself on you. She went against everything she wanted to believe in and you didn’t even appreciate it, you didn’t love her and she knew it, she told me herself. She told me in the hospital asking my forgiveness.” Ronnie takes breath to go on, but tears block his throat.

Rabbit’s own throat aches, thinking of Thelma and Ronnie at the last, her betraying her lover when her body had no more love left in it. “Ronnie,” he whispers. “I did appreciate her. I did. She was a fantastic lay.”

“You c*cksucker” is all Ronnie can get out, repetitively, and then they both turn to face the mourners waiting to pay their respects

457. [Rabbit], having to arise at least once and sometimes, if there’s been more than one beer with television, twice, has learned to touch his way across the bedroom in the pitch dark, touching the glass top of the bedside table and then with an outreached arm after a few blind steps the slick varnished edge of the high bureau and from there to the knob of the bathroom door. Each touch, it occurs to him every night, leaves a little deposit of sweat and oil from the skin of his fingertips; eventually it will darken the varnished bureau edge as the hems of his golf-pants pockets have been rendered grimy by his reaching in and out for tees and ball markers, round after round, over the years; and that accumulated deposit of his groping touch, he sometimes thinks when the safety of the bathroom and its luminescent light switch has been attained, will still be there, a shadow on the varnish, a microscopic cloud of his body oils, when he is gone.

467. (Nelson was hooked on coke, and he bankrupted the family car dealership. And now he’s sober.)

Nelson tells [Rabbit], in that aggravating tranquillized nothing-can-touch-me tone, “You get too excited, Dad, about what really isn’t, in this day and age, an awful lot of money. You have this Depression thing about the dollar. There’s nothing holy about the dollar, it’s just a unit of measurement.”

“Oh. Thanks for explaining that. What a relief.”

472. Expansively [Rabbit] says to Ronnie as they ride the cart to the eighteenth tee, “How about that Voyager Two? To my mind that’s more of an achievement than putting a man on the moon. In the Standard yesterday I was reading where some scientist says it’s like sinking a putt from New York to Los Angeles.” Ronnie grunts, sunk in a losing golfer’s self-loathing. “Clouds on Neptune,” Rabbit says, “and volcanos on Triton. What do you think it means?”

One of his Jewish partners down in Florida might have come up with some angle on the facts, but up here in Dutch country Ronnie gives him a dull suspicious look.

“Why would it mean anything? Your honor.”

Rabbit feels rubbed the wrong way. You try to be nice to this guy and he snubs you. He is an ugly prick and always was. You offer him the outer solar system to think about and he brushes it aside. He crushes it in his coarse brain.

519. They did do some fun things, [Rabbit] and Jan. The thing about a wife, though, and he supposes a husband for that matter, is that almost anybody would do, inside broad limits. Yet you’re supposed to adore them till death do you part. Till the end of time.

531. So when the system just upped one summer and decided to close Kroll’s down, just because shoppers had stopped coming in because the downtown had become frightening to white people, Rabbit realized the world was not solid and benign, it was a shabby set of temporary arrangements rigged up for the time being, all for the sake of the money.

590. [Rabbit’s dying words.] “Well, Nelson,” he says, “all I can tell you is, it isn’t so bad.” Rabbit thinks he should maybe say more, the kid looks wildly expectant, but enough. Maybe. Enough.

—–Begin excerpts from “Rabbit Remembered” by John Updike—–

199. A slender dark-browed girl of startling beauty waits on Janice, such beauty among the middle-aged and pudgy pimpled teen-age other waitresses that Janice’s eyes sting [with a vision of the girl’s] sad future: the marriage, the pregnancies, the heavy meals, the lost looks. The blazing beauty dwindled to a shrill spark, a needle of angry discontent lost in these streets lined with row houses and aluminum awnings and little front porches where the patient inhabitants sit and soak in the evening heat and wonder where it all went.

232. When Nelson tries to picture what a schizophrenic sees he remembers [doctor] Howie Wu telling him, Their sense of distance has broken down. Things up close look far away, is how Nelson has framed this—there is no clear depth in which to locate yourself. The gears that notch us one into another fail to mesh, maddeningly, meltingly. Trying to think his way into [patient] Michael’s head plants a sliding knife inside Nelson, a flat cold queasy sensation below his ribs.

266. [Nelson] is afraid getting back into circulation might get him back into coke, or Ecstasy if that’s the thing, or the ever-cheaper heroin; it’s so easy to slip back when you don’t feel you have much to lose. Talking to the substance abusers at Fresh Start, he can’t much argue when they argue for it. Happiness is feeling happy. Maybe it shortens your life but when you’re dead what’s the diff? Living to the next hit, the next scrounged blow-out, gives their lives a point. Being clean exposes you to life’s having no point.

[With my publicist Patty Garcia, who told me about meeting Updike.]

274. Mim: “Vegas is dead, the way it was—a sporting town. The people used to come here had a little class—the gangsters, the starlets. A little whiff of danger, glamour, you name it. Class. The guys used to pay cash for everything, off a big roll of fifties. Now it’s herds. Herds and herds of Joe Nobodies. Bozos. The hoi polloi, running up credit-card debt. Gambling is legal in half the states so they’ve built these huge moron-catchers along the Strip, all the way to the airport. A Pyramid, the Eiffel Tower, Venice—it’s all here, Nelson, all for the morons. It’s depressing as hell.”

306. She [Janice] and Ronnie left alone tended to each other’s needs, one of which, never stated, was getting ready for death, which could start any time now. A pain in the night, a sour number on the doctor’s lab tests,

311. (Pru telling her estranged husband Nelson about their geeky son Roy)

“He’s is scary, of course, spending so much time at the computer, but a lot of his friends are like that too. Where you and I see a screen full of more or less the same old crap, they see a magic space, full of tunnels and passageways and pots of gold. He’s grown up with it.”

Nelson is being invited, he realizes, to talk as a parent, a collaborator in this immense accidental enterprise of bringing another human being into the world. “Yeah, well, there’s always something. TV, cars, movies, baseball. Lore. People have to have lore. Anyway, Roy has always been kind of a space man.”

323. Seeing [childhood friend Billy Fasnacht], Nelson cannot but warm: here is a partner in his childish dreams, the conspiracy of imagined speed and triumphant violence that boys erect around themselves like a tent in the back yard under the scary stars.

325. Billy: I’m going to die, I can’t get it out of my head.

Nelson: By our age, Billy, we should have come to terms with this stuff.”

Billy: “Have you?”

Nelson: “I think so. It’s like a nap, only you don’t wake up and have to find your shoes.”

November 4th, 2021 at 11:04 pm

“How can you respect the world when you see it’s being run by a bunch of kids turned old?”

I grew up and moved away and never went back, and it’s difficult to imagine what it must be like “back home”, the kids getting old. Those same people all still existing, not needing me to observe them. It’s hard not to feel that maybe they were just a book I read long ago.