I wrote this post on Feb 7, 2017, and then I rewrote it, making it about twice as long, on Feb 11, 2017. It got longer because I learned more about Raymond Chandler.

I’ve been reading a lot of Raymond Chandler over the last few weeks. He wrote seven novels: (1) The Big Sleep, (2) Farewell My Lovely, (3) The High Window, (4) The Lady in the Lake, (5) The Little Sister, (6) The Long Goodbye, (7) Playback. I’ve read them all now, totally binged on them, couldn’t stop, kept going back to Amazon for another one-click Kindle purchase.

For what it’s worth, I think Farewell My Lovely is the best, and I’d put The Little Sister in second place, even though when it came out, it was poorly reviewed. Often the first four are viewed as the core of his work, they appeared in a short period of time,

I also read most of Tom Hiney’s Raymond Chandler biography (Atlantic Press, 1997). Chandler was born in Chicago in 1888, but spent most of his childhood in England and Europe. He moved to the US when he was about 25, and ended up on LA. He married Cissy, a woman 18 years older than him, when he was 36. From 1922 to 1932 he worked at the Dabney Oil Company. We was writing some poems for fun, but no fiction.

His alcoholism took over in this forties, and he was fired from his job when he was 44, that is, in 1932. At this point he seems to have totally given up drinking for a number of years, maybe as for as long as ten years. He spent the next six years learning how to write—by writing tales for such pulp detective magazines as Black Mask. He wrote and sold his first novel, The Big Sleep, when he was fifty.

(1) The Big Sleep (1939) has some of the jazz and glamour of being his first, and some great lines. The plot is insanely tangled. It’s sort of two plots, one after another. When they were filming the classic Bogart / Bacall version of the movie, supposedly one of the screenwriters telegraphed Chandler to ask him who actually killed the chauffer who dies right near the start..or was it a suicide. Supposedly our man’s answer was NO IDEA.

There’s this great sexy-woman description of a tough cookie named Agnes. She’s at the reception desk of a fake antiquarian bookstore which is actually a porn library. Marlowe pretends to be a nerd looking for a rare book.

She got up slowly and swayed towards me in a tight black dress that didn’t reflect any light. She had long thighs and she walked with a certain something I hadn’t often seen in bookstores. She was an ash blonde with greenish eyes, beaded lashes, hair waved smoothly back from ears in which large jet buttons glittered. Her fingernails were silvered. In spite of her get-up she looked as if she would have a hall bedroom accent.

She approached me with enough sex appeal to stampede a business men’s lunch and tilted her head to finger a stray, but not very stray, tendril of softly glowing hair. Her smile was tentative, but could be persuaded to be nice.

“Was it something?”” she inquired

I had my horn-rimmed sunglasses on. I put my voice high and let a bird twitter in it. “Would you happen to have a Ben Hur 1860?”

I just wonder what a “hall bedroom accent” is.

Later we meet Carmen Sternwood, a very wild girl, maybe a little crazy. She has an unsettling giggle. “The giggles got louder and ran around the corners of the room like rats behind the wainscoting.”

(2) Farewell my Lovely (1940) is dynamite, a masterpiece from beginning to end. A couple of nice quotes.

Like, Marlowe is talking to a big tough guy. The guy introduces himself: “I’m called Moose, on account of I’m large.”

A sharp woman enters Marlowe’s office. Love the fashion description. So late 1930s.

“Her hair by daylight was pure auburn and on it she wore a hat with a crown the size of a whiskey glass and a brim you could have wrapped the week’s laundry in. She wore it at an angle of approximately forty-five degrees, so that the edge of the brim just missed her shoulder. In spite of that it looked smart. Perhaps because of that.”

Marlowe examines a photo of a woman involved in the case.

“It was a blonde. A blonde to make a bishop kick a hole in a stained glass window. She was wearing street clothes that looked black and white, and a hat to match and she was a little haughty, but not too much. Whatever you needed, wherever you happened to be—she had it.”

Here’s Marlowe wandering in a beachside amusement park. So classic.

“Beyond the electroliers, beyond the beat and toot of the small sidewalk cars, beyond the smell of hot fat and popcorn and the shrill children and the barkers in the peep shows, beyond everything but the smell of the ocean and the suddenly clear line of the shore and the creaming fall of the waves into the pebbled spume. I walked almost alone now. The noises died behind me, the hot dishonest light became a fumbling glare. Then the lightless finger of a black pier jutted seaward into the dark. This would be the one. I turned to go out on it.”

As I mentioned, Chandler was a very heavy drinker until the age of 44, and later on, when he began working for Hollywood around age 55, he again began drinking a lot. All along, his characters drink a lot. Up until twenty years ago, I used to drink a lot, and I’m familiar with the transfer mechanism.

You’re writing, and wishing you could have a drink, but maybe putting that off because you want to be sharp for the writing, or maybe you’ve stopped drinking entirely just in order to survive, but you really really want a drink—so you let your character have a few, or more than a few. Even now I kind of miss drinking and getting high, so it’s not that unusual for me to have some of characters catch a buzz. Letting your characters get drunk and stoned is, in a way, not so different from letting them be able to fly, or travel in time, or have sex with lots of people. Wish fulfillment.

(3) The High Window (1942) has a good neurasthenic mousy woman who thinks she murdered a man, but maybe she didn’t. She’s a secretary for a rich lady. Marlowe is grilling her about a showgirl named, wait for it, Lois Magic.

“Okay, what does Miss Lois Magic look like?”

“She’s a tall handsome blond. Very—very appealing. ”

“You mean sexy?”

“Well—” she blushed furiously, “in a nice well-bred sort of way, if you know what I mean.”

“I know what you mean,” I said, “but I never got anywhere with it.”

.

“I can believe that,” she said tartly. .She leaned back in her chair and put her small neat hands on her desk and looked at me levelly. “I wouldn’t carry that tough-guy manner too far, if I were you, Mr. Marlowe. Not with me, at any rate.”“I’m not tough,” I said. “Just virile.”

She picked up a pencil and made a mark on a pad. She smiled faintly up at me, all composure again. “Perhaps I don’t like virile men,” she said.”

(4)The Lady in the Lake 1943. Even though Chandler was still doing his stint as a tee-totaller, you get the feeling he’s sick of it, and alcohol is kind of taking over the plot. I think at this point Chandler is a little fed-up with his thus-far-commercially-unsuccessful novels. Marlowe is depressed. The death of one of the characters is really nauseating—she’s found decomposed under being under a dock in a lake for a month. Oook!

But there’s tons of good stuff too. One of Chandler’s strong points is description—of clothes, faces, houses, and landscape. Very concise and poetic. Like haiku almost. Here’s a lovely description of a lake resort that Marlowe drives up to. Not a single word out of place.

The road skimmed along a high granite outcrop and dropped to meadows of coarse grass in which grew what was left of the wild irises and white and purple lupine and bugle flowers and columbine and penny-royal and desert paint brush. Tall yellow pines probed at the clear blue sky. The road dropped again to lake level and the landscape began to be full of girls in gaudy slacks and snoods and peasant handkerchiefs and rat rolls and fat-soled sandals and fat white thighs. People on bicycles wobbled cautiously over the highway and now and then an anxious-looking bird thumped past on a power-scooter.

A mile from the village the highway was joined by another lesser road … I turned the Chrysler into this and crawled carefully around huge bare granite rocks and past a little waterfall and through a maze of black oak trees and ironwood and manzanita and silence. A bluejay squawked on a branch and a squirrel scolded at me and beat one paw angrily on the pine cone it was holding. A scarlet-topped woodpecker stopped probing in the dark long enough to look at me with one beady eye and then dodge behind the tree trunk to look at me with the other one.

And here’s a very cute little subroutine or mini-story threaded through a couple of chapters of The Lady in the Lake . (I should explain that an old-fashioned PBX is a “private branch exchange” with an operator and a switchboard with plugs in it.)

A neat little blonde sat off in a far corner at a small PBX, behind a railing and well out of harm’s way.

…The little blonde at the PBX cocked a shell-like ear and smiled a small fluffy smile. She looked playful and eager, but not quite sure of herself, like a new kitten in a house where they don’t care much about kittens.

…The Gillerlain Company’s reception room looked even emptier than the day before. The same fluffy little blonde was tucked in behind the PBX in the corner. She gave me a quick smile and I gave her the gunman’s salute, a stiff forefinger pointing at her, the three lower fingers tucked back under it, and the thumb wiggling up and down like a western gun fighter fanning his hammer. She laughed heartily, without making a sound. This was more fun than she had had in a week

…I walked back down the room and out. The little blonde at the PBX looked at me expectantly, her small red lips parted, waiting for more fun.

I didn’t have any more. I went on out.

Shortly after this novel, in 1944, Chandler started getting work as a screenwriter in Hollywood starting with James M. Cain’s Double Indemnity. He made hundreds times as much money off his film work as off his writing. He also started drinking heavily again—there’s a famous story of his drinking writing the script for The Blue Dahlia in 1946. But I’ll post about his screenwriting career another time.

(5) In The Little Sister,(1949) Chandler’s in great form. He’s been in Hollywood for six years since Lady in the Lake. Lots of drinking in the novel , but it’s kind of funny, and it’s maybe a little more playful given that he’s no longer holding back. Great scene with a sodden gin-soaked landlady in a rooming house. And the villain, the little sister of the title, is ter4ifict. There’s some priceless dialog between her and Marlowe. She’s talking to him in his office, She’s come to LA from Manhattan, Kansas, supposedly in search of her brother. It’s clear she’s holding back on the facts.

Marlowe: “I’ll tell you what’s wrong. I’ll skip over your not telling me where you’re staying, because it might be just that you’re afraid I’ll show up with a quart of hooch under my arm and make a pass at you.”

“That’s not a very nice way to talk,” she said.

“Nothing I say is nice. I’m not nice. By your standards nobody with less than three prayer-books could be nice. But I am inquisitive…” [Marlowe then sums up the facts of the case as he sees them.]

She came to her feet with a lunge. “You’re a horrid, disgusting person,” she said angrily. “I think you’re vile. Don’t you dare say mother and I weren’t worried [about my brother.] Just don’t you dare.”

As it turns out the little sister isn’t really worried about her brother, and she’s a completely crooked person, but with a goodie-goodie façade. Like a smarmy evangelical preacher you might say, or like any number of recent cabinet appointees, not that I want to go there. Anyway, I loved this book.

(6) The Long Goodbye (1953) came four years later, shorlty after Chandler dropped his movie career, and it’s almost twice as long as the others, and reads, at times, like a parody of Chandler. Like a Guy Noir episode on Prairie Home Companion, but not in a good way. And it’s weighted down with gloomy pronouncements on what’s wrong with the world at large. Chandler is 65, and feeling a little fried. The book was, for whatever reason, reviewed more favorably than his tight, hard-core hard-boiled novels. It’s like the way critics might like some puffy wheenk-wheenk-wheenk SF novelabout feelings—more than a hardcore nihilistic cyberpunk work.

A larege proportion of The Long Goodbye revolves around alcoholism: blackouts, rehab cures, alcoholic suicides, and drinks, drinks, drinks. One of the characters is even an alcoholic author of best-selling books. Of course Philip Marlowe repeatedly claims he can control his own drinking. He’s not like the others. Naaah. Even if he’d rather drink champagne than make love to the luscious Linda Loring. Kind of sad.

Here’s Linda.

“She shut the door and turned. She had loosened her hair and she had tufted slippers on her bare feet and a silk robe the color of a sunset in a Japanese print. She came towards me slowly with a sort of unexpectedly shy smile. I held a glass out to her. She took it.”

Oh well!

She’s rich and she’s in love with Marlowe, too. But he’s not ready.

(7) Playback (1958) came shortly before Chandler died, a final novel, based on a screenplay he’d never finished. The plot of this one is pretty weak, but he has some good lines…he’s having fun with writing a “Chandler novel,” almost mocking it a times, and sticking in any old thing. The dude is seventy! His biographer Tom Hiney suggests that Chandler might have actually been drunk during the hours he worked on this book. But there’s some good stuff.

She was an outdoorsy type with shiny make-up and a horse tail of medium blond hair sticking out the back of her noodle.

Love him using the word “noodle.”

Here’s an example of Ray kind of laughing at himself, and at his imitators. A tough babe talking to him.

Then she leaned back and gave me the look.

“I’ve got friends who could cut you down so small you’d need a stepladder to put your shoes on.”

“Somebody did a lot of hard work on that one,” I said. “But hard work’s no substitute for talent.”

Suddenly we both burst out laughing.

As synchronicity would have it, just before reading Playback, I took a nice photo of a bird of paradise flower in the rain. I was using my heavy-duty Canon SRT 5D with a really long lens, and I had “film speed” set down to 100, so the lens aperture is very wide, which means I got great “bokeh,” which is the quality of having only the picture plane object be in focus. I love how alert a blossoming bird of paradise blossom looks. Like a donkey looking over a fence.]

And then in Playback I found this passage:

Very small things amuse a man of my age. A hummingbird, the extraordinary way a strellitzia bloom opens. Why at a certain point in its growth does the bud turn at right angles? Why does the bud split so gradually and why do the flowers emerge always in a certain exact order, so that the sharp unopened end of the bud looks like a bird’s beak and the blue and orange petals make a bird of paradise?

And, guess what, at the end of Playback , Phillip Marlowe decides to marry his lost love, Linda Loring of The Long Goodbye!

Here’s to you, Ray!

In 1953, Raymond Chandler wrote a little spoof of SF in a letter that’s quoted in Tom Hiney’s bio of him. Would have been cool if our man Ray had written some SF, but, hey, he was born in 1888. As William Gibson has remarked, Chandler was real influence on us cyberpunks.

And indeed my novel Wetware opens with a Chandler-like scene of my character Sta-Hi or Stahn Mooney working as a private detective out of an office on the Moon. Dealing with the doings of the intelligent robots called boppers. The guy Yukawa who phones Stahn was in fact modeled by me on Gibson himself. That long, thin, flexible head.

It was the day after Christmas, and Stahn was plugged in. With no work in sight, it seemed like the best way to pass the time . . . other than drugs, and Stahn was off drugs for good, or so he said. The twist-box took his sensory input, jazzed it, and passed it on to his cortex. A pure software high, with no somatic aftereffects. Staring out the window was almost interesting. The maggies left jagged trails, and the people looked like actors. Probably at least one of them was a meatie. Those boppers just wouldn’t let up. Time kept passing, slow and fast.

At some point the vizzy was buzzing. Stahn cut off the twist-box and thumbed on the screen. The caller’s head appeared, a skinny yellow head with a down-turned mouth. There was something strangely soft about his features.

“Hello,” said the image. “I’m Max Yukawa. Are you Mr. Mooney?”

Without the twist, Stahn’s office looked unbearably bleak. He hoped Yukawa had big problems.

“Stahn Mooney of Mooney Search. What can I do for you, Mr. Yukawa?”

“It concerns a missing person. Can you come to my office?”

“Clear.”

It’s been raining like a mofo. I’m picking up hyperspace signals in High Martian, trying to firm up the ideas for this story called “Black Bucket” that I’m working on with Bruce Sterling.

What, him again? I never learn. This photo is from about 1995, shot a party on our deck held in the visiting Bruce’s honor. I pretty sure that in this photo I’m drunk. I’m practically choking Bruce, and he’s being patient with me.

“The Elephant Bush” acrylic on canvas, January, 2017, 24” x 20”. Click for a larger version of the painting.

I finished a new painting last week, of a little boy seeing some cute little flying elephants who live in a plant they call an “elephant bush.” Rudy Jr. recently got such a bush at his local Loew’s Lumber. I started thinking about the possibilities, actualized them, and gave the painting to Rudy’s four-year-old son. Hung it right on his wall. I think he likes it

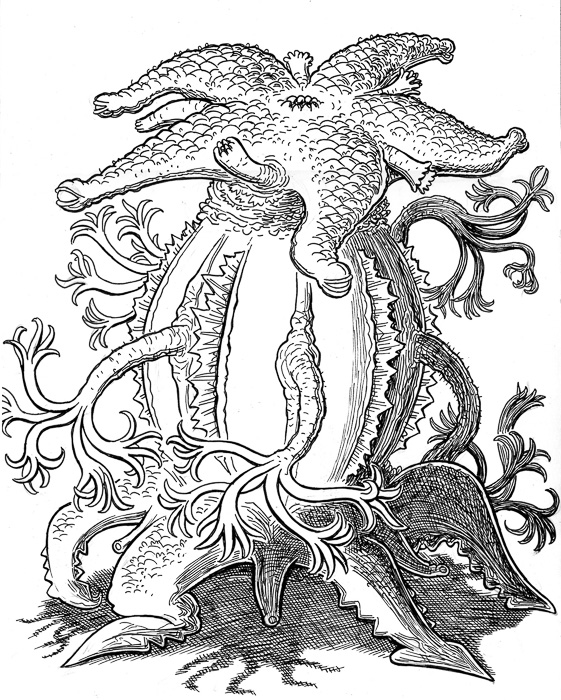

Here’s an illustration of one of the “Elder Ones” or what personally call “sea-cuke men” by Jason Thompson. These critters are in H. P. Lovecraft’s masterpiece, “At the Mountains of Madness,” which I reread in January. I’d like to work some of these creatures, or at least their vibes, into my projected next novel project, Return to the Hollow Earth. Still not quite sure how to set the book up. It could be a second journal by Mason Reynolds, from the 1890s. Or it could be a hoaxing first-person account of my own trip into the Hollow Earth, accomplished quite recently using a stolen replica of James Cameron’s Deepsea Challenger. Stay tuned.

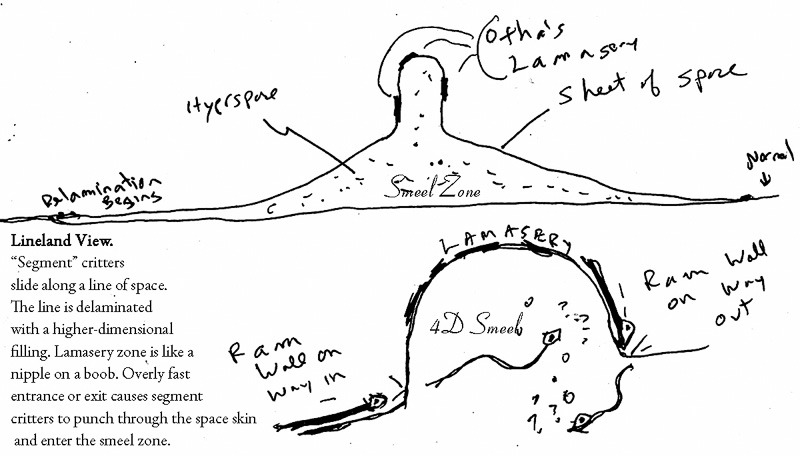

I think I’ll go down the coffee shop and try and convert this diagram I made into the next segment of my story with Bruce. “Black Bucket,” yes. And, yes, I do remember what the drawing means. Come by my Moon office and we can talk about it. Take a dip in that pouch of 4D Smeel maybe…

Still raining, still dreaming.

February 7th, 2017 at 1:28 pm

Hey I don’t see any comments but someone’s gonna remind you about The High Window, which is swell fun and the first novel he wrote from scratch (i.e., without “cannabilizing” his shorter works). Also there’s Playback, a good screenplay turned into a blah Marlowe novel. (Shoulda left the main character as is, mighta been a nice book.)

February 7th, 2017 at 5:08 pm

The screenwriter trying to figure out the convoluted plot of “The Big Sleep” was a fellow named William Faulkner.

February 7th, 2017 at 9:35 pm

I have a notebook from a few years ago, when I read a few Chandler books. Some of the lines I wrote down, although I don’t recall which books they were from:

“I got a hangover like seven Swedes.”

“The roar of his laughter was like a tractor backfiring.”

“The elevator had an elderly perfume in it, like three widows drinking tea.”

“His remarks fell to the ground, eddying like a soiled feather.”

“The dollar went into his pocket with a sound like caterpillars fighting.”

February 16th, 2017 at 4:04 am

Haven’t been here in awhile, thought I’d take a peek at what you’ve been up to…

Found your essay on the formula fiction writer Raymond Chandler interesting in juxtaposition with your visual work. I am continually impressed with the contrast between the stark maturity of your photos and the vibrant playfulness of your illustrations. Like the two halves of your brain in an endless conversation with each other – each one bringing to consciousness what the other one cannot. It’s an interesting pas de deux.

In any case, it looks like Mr Chandler provided you with some useful company, and your art made interesting company with him as well. Another ballet of ideas, it seems.

February 16th, 2017 at 9:35 am

Thanks for the comments!

* Eddie Evers, as you see, I went back and added High Window and Replay.

* Barney, I watched “Big Sleep” on VUDU, and enjoyed it, although as a film it feels more confusing than as a novel. Also of course they had to drop and/or blur some things for the censors. Ineresting that Faulkner wrote the screenplay. As a writer, he respected our man Chandler enough to simply collage in great swathes of the book’s dialog, which is all to the good.

* Gary Singh, I love those Chandler similes too. I recently realized that, when reading a novel on Kindle, I can highlight a passage, choose Highlight on the popup, and then when I’m done, open the Notes (and Highlights) and Export them as an email to the Kindle device owner, that is, me. And then I have a bunch of text that I can paste into something like…a blog post!

* womans_voice, I always appreciate your kind and thoughtful remarks..