Today’s post is about the photographer Garry Winogrand and wide-angle lens street photos. If you don’t know anything about Winogrand, here’s good lengthy link-laden post by the photographer Eric Kim. Or, even simpler, you can do what I’ve been doing lately, just do a Google image search.

There’s a big Winogrand show at the SFMOMA just now, which is what got me focused on him again. With (here’s links to more Google Image searches) Lee Friedlander and Diane Arbus, and Robert Frank, Winogrand was one of the last really renowned black-and-white photographers. In the mid-1970s, William Eggleston flipped the game over to color photography.

Winogrand used a wide-angle lens (I think 28 mm) on a Leica M4 film camera. As it happens, I used Leicas when I shot film in the 1960s – 1990s, and I have a very nice German-built 28 mm Leica lens that, with a slight bit of effort, I can use on my digital Canon full-frame 5D. So for the last week or two, I’ve been shooting “Winogrand” style, using that lens.

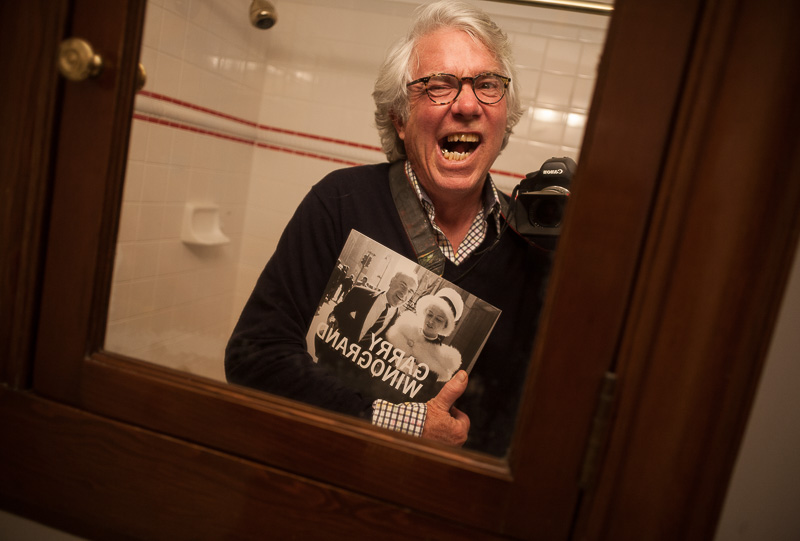

With a wide-angle lens, you can stand really close to someone to get their picture. Winogrand was a fairly pushy guy, I think. So I took an ugly picture of myself clutching my new ten-pound-heavy (?) Winogrand catalog. Recently I’ve been trying to make a brand-new ugly face in the mirror before bedtime every day. I’ve got kind of a Lee Harvey Oswald being shot by Jack Ruby thing happening for me here. With a 28 mm lens it’s pretty easy to shoot in a mirror. Not that I’m going to pursue that in any relentless kind of way.

Your average pocket digicam has a 28 mm lens zoom mode of course. But those cameras don’t really pick up the tonal range that you can get with a heavy duty SLR with some quality glass. I’d toyed with the idea of buying a new Canon 28 mm lens. But those things, they weigh over one pound each. And, like I say, I had this lens right here. My camera body has paint on it because one of the main things I use it for these days is getting shots of my paintings—walking about I’m more likely to have my latest pocket-sized digicam. But now I want to do the lugging routine again for awhile. Like in the old days.

This is our friend Paul and his wife Lydia. They helped organize an Easter picnic that I went to with my son and his family today. Paul’s theatrical, an artist, and he emcees in his pink rabbit suit. So San Francisco.

Most of Winogrand’s pictures are of people—really his primo shooting spots were the crowded cross-walks in Manhattan. So many faces going by. Legally you can shoot a stranger’s picture and sell prints of it and put it in a book, as long as you don’t put defamatory comments about the person. I’ve never had the right personality for getting up close to complete strangers and snapping them.

Another issue about Winogrand—which I won’t delve into at length here—is that he was really into getting photos of passing women whom he considered attractive. And photos of down-and-outers. There can be predatory aspect to street photography, and it can become disturbing. This said, photos of people really are interesting.

Diane Arbus took a different approach than Winogrand did. She’d hang around with her subjects, at least for a few minutes, sometimes for hours, sometimes for days. Really getting to know them. And in her photos you sometimes have the feeling the subjects are looking at Diane and thinking, “This woman is really strange.”

Winogrand was more about the grab shot—although he said he was never surreptitious about it, he’d be looking through his viewfinder. And he’d try to defuse the tension by smiling at the subject.

When you’re comfortable with it, it easy to grab shots of people with the wide-angle lens. The lens has a large depth of field. You only need to set an approximate distance. (The autofocus feature doesn’t work when you marry an old lens to a new camera like I’m doing.)

Another thing about wide-angle lens photography is that the horizon line becomes less important to you. If you’re using a single-lens-reflex, you’re looking through the lens, turning it this way and that, trying to fit more of the world in, composing you scene. Why is the standard horizontal and vertical so sacred? Let it go. Big inspiration from Winogrand.

People would ask him why his photos were tilted and with a straight face (he was stubborn), he’s insist they weren’t tilted. “That’s how the picture is.”

But, like I say, I’m not going out and shooting strangers. I’m happy with something like the sun on these drops of juice.

It’s kind of disappointment to drop back and do a non-tilted shot. Kind of a Joseph Cornell box thing here. That red rubber thing is the mighty flying Troton, an insufficiently recognized and seldom used beach toy.

Landscapes get a looming, creepy look with the wide lens. This is the brain-wave controller device atop Bernal Hill.

It is of course possible to take bad wide-angle lens pictures. You need to have stuff in them. In the last years of his life Winogrand was living in LA, which unlike NYC, is pretty dead on the streets. And he shot, like, a hundred thousand mostly bad pictures of empty streets with like one person half a block away. Reading between the lines, I get the feeling that he was drinking very heavily at this point. His friendlier critics have struggled for some years to find nuggets in the dross of Winogrand’s later work, and there are a handful. But, hey, sometimes when you’re old, you lose it.

Like this guy…