So I’m well now. Thanks, all, for the kind wishes and the birthday greetings.

I’ve been taking a lot of photos lately, so today I’ll just run some photos with some recently arrived links, some remarks about the current state of my free software…plus a discussion of Jonathan Lethem’s Chronic City with a particular focus on the question, “What is a chaldron?”

My artist friend COOP told me about a site with information about Kanegon—if you scroll way down on the page linked to, you can find some video of Kanegon, who’s played by a guy in a rubber monster suit with a kind of garbage-can-top head mask—actually it’s a giant change purse. COOP sent me a great photo he took of his Kanegon models, seductively lit with colored lights. For more along these lines…and along other lines…see COOP’s photostream.

I got a Kanegon model for Xmas a few years back, and I modeled the Unipusker aliens of my novel Frek and the Elixir on them.

[A Buddha in the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco.]

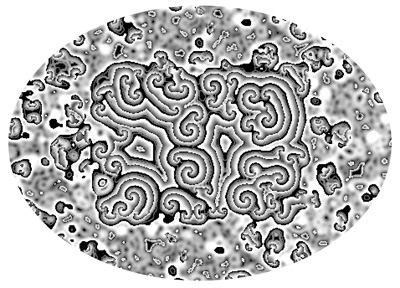

My young friend Eamon Carrig sent me a link to an interesting article about common forms of hallucinations as being somewhat predetermined as emergent chaotic patterns of the brain architecture—a little like how Zhabotinsky scrolls always turn up in cellular automata simulations. Eamon is part of an unclassifiable band called Math Panda, and runs a record company called FARC, for, “F*ck a Record Company,” this being an answer to the perennial question, “What’s your record company?”

I read Jonathan Lethem’s latest novel Chronic City a couple of months ago. I’m always interested to see what Lethem’s up to. Some years ago he might have been regarded as science fiction writer—see, for instance, the wonderful As She Climbed Across the Table. But somehow Jonathan completed the arcane and mysterious metamorphosis into a mainstream literary author.

A spoiler alert—some of the things I’ll say about Chronic City here will give away plot points, so if you haven’t read the novel yet, you might not want to read my comments yet.

I liked Chronic City a great deal, although I have a few minor complaints. Although it was to some extent a novel about potheads, I didn’t get enough of the raucous yellow-jello giggle vibe that one would typically expect from the stoner scenes—although, in all fairness, there were plenty of convoluted and paranoid rants.

The book felt a little overlong to me, with more scenes than necessary about people’s relationships and inner feelings. I tend to prefer seeing interesting things happening. Actually, Phil Dick’s novels also have the characteristic of going on and on about the characters’ worries and feelings. This is a writing quality that I call “wheenk,” because it makes me think of a trapped rabbit going, “Wheenk, wheenk, wheenk,” in terror and despair. But tastes vary, and a large amount of wheenk is probably helpful in making it out of the SF ghetto.

My largest criticism would be that Chronic City seems to drop the ball on one of the key SFictional elements in the book. I’m talking about the gorgeous, pricy, vase-like objects called chaldrons, no two of which are alike. After building up intense interest in the chaldrons, Jonathan rather abruptly dismisses the chaldrons as somehow being both (a) imaginary virtual reality icons like little accessories that you might buy in some online game such as The Sims, and (b) real-world hologram displays being created by individually tweaked software algorithms.

First of all, I’d been hoping that the chaldrons would be something with a little more SFictional punch—like aliens, or concretizations of Blavatsky-ectoplasm, or nanogoo growths.

Be that as it may, the real problem is that Lethem’s two explanations for the chaldrons don’t seem to jibe—how do they connect with each other? And why exactly are chaldrons rare and expensive?

If I were to fix this flaw, I might propose that some behind-the-scenes computer genius is crafting algorithms that create the chaldron shapes—one algorithm per chaldron. And he or she is selling the algorithms in two alternate forms: either (a) as plug-ins that create an image of the chaldron within your game world, or (b) as some chip-embedded (and encrypted) software that can be placed in a tabletop hologram generator that will display a stand-alone image of the chaldron.

Possibly—although Jonathan doesn’t say this, and (frustratingly) we never see anyone successfully buying a chaldron—when you buy a chaldron, you get both the standalone display and the game plug-in.

To make this explanation really percolate, you’d want for the algorithm-discovery-method to plug into a Perkus-Tooth-type paranoid obsession with the patterns of society. So maybe the algorithms aren’t so much based on formulae as on statistical power-spectrum analyses of pop-culture stuff that people are doing. The number of bags of popcorn sold in a certain movie theater. The page hitcounts on our hero’s dying or dead astronaut wife. The number of hairs on a Gnuppet. The shapes of all the burgers sold in a favorite Wild West style café. The chaldrons emerging from the actual life of the virtual Chronic City.

Anyway, the chaldron explanation is a little muddled and incomplete as it stands, and if I were Lethem, I’d consider correcting it in time for the paperback edition of Chronic City, but of course that’s not a realistic suggestion.

Even though I’m acting like I know what I’m talking about, I have a lingering feeling that maybe I’m missing something. One of the pervading images in Chronic City is of Manhattan as a kind of alternate reality—akin to a videogame world. This is a good simile, as it fits the feeling that you get when living in or visiting there. Might Lethem want to be saying that, in fact, the world of his novel is in fact an artificial reality? We’d have to accept that the “gnats in a bottle” characters are in fact entertaining themselves with a yet smaller VR inside theirs. In this case, the two explanations of the chaldrons are even more closely related, by the way.

I’m inclined to think that Jonathan might not want to use by-now-somewhat-tired Matrix-type (or, indeed, Dickian) move of saying “the characters are in a virtual reality and they don’t know it.” But SF is, after all, largely about recycling tropes, so maybe that’s what he’s doing. There are a couple of magical-realism aspects of the “Chronic City” that suggest that some deeper weirdness is in play.

The most conspicuous of these is the tiger that keeps destroying parts of the city. Earlier in the novel, people are saying the tiger is “just” an artificially intelligent digging machine that now and then goes rogue. But near the end, in a haunting scene, our hero sees the tiger go padding by in the falling snow, huge and magical.

And at the very end, the narrator notices that the positioning of the buildings he sees out his window have very slightly changed. Is there a coherent explanation? In some sense this isn’t the most important question. SF is really a kind of surrealism. And the explanations that we tack on are just a genre convention. When I’m writing SF, I very often simply go for the effect that I want to see—and make up the “explanation” later. People unused to SF don’t actually care about the explanations anyway. They just enjoy the wonder of the unsettling events.

What is reality?

Lethem has a beautiful writing style, and the characters are memorable, with great dialog. One of the characters is being interviewed by the New Yorker profile, and the quirky outsider Perkus Tooth asks him, “How does it feel to finally ride the hegemonic bulldozer?” There’s a transreal touch, given that, being a regular contributor to the New Yorker, Jonathan himself is definitely on the bulldozer. And we genricized SF writers are more like Perkus Tooth…

It’s worth mentioning that Lethem has done great service for the SF field in editing three collections of Phil Dick’s novels in classy Library of America editions.

Last fall Lethem wrote a fascinating, dreamy essay about Phil Dick, “Crazy Friend,” which he put online at his website. It’s a searching, thoughtful piece that almost makes me ashamed to be nitpicking against Chronic City. Lethem very clearly knows what he’s doing with his writing, and there’s really no reason it should conform to my personal expectations.

There’s a wonderful show of Wayne Thiebaud’s paintings at the San Jose Art Museum. How did my humble home city of San Ho score such an illustrious show? Well, they’ve had a couple of big Thiebaud shows at the San Francisco museums in the last ten years, so we got to have this one. It’s mostly paintings from the Thiebaud family collection, many of which I’d never seen before.

Thiebaud is just about my favorite contemporary artist. He has an amazing ability to dig the gnarl out of the most ordinary kinds of scenes—he’s done lyrical, cosmic paintings of freeways, for instance. I like how he uses color too, the edges he puts on things. And he’s a master at dancing between abstraction and realism, staying right on that edge.

[Spring at the mall, Santa Clara, California.]

I upgraded to the 64-bit version of the Windows 7 operating system this week, and I’m still tweaking my machine. I made the sad discovery that some of my free software isn’t working on this platform, although it survived the last five or six revisions of Windows. Cellab, Chaos, and Boppers have all fallen beneath the karmic hammer.

John Walker wrote most of the code for Cellab, and he probably could upgrade it to work in the latest Windows—knowing John this would take him about one day. But, no—I asked him about this, and he says he no longer has any Microsoft software on any of his machines. Regarding my description of Windows 7 as an upgrade, he says, “Then it wasn’t an upgrade, was it? Sounds like they blew away 16 bit DOS emulation support.” Continuing in his characteristically passionate-about-programming style, he writes:

I can’t understand any developer who doesn’t make money from it wanting to be jerked around like a monkey on a chain by Microsoft, screeching “OOK” and jumping on the keyboard every time one of their “upgrades” breaks existing software developed with their own tools and compliant with all the standards for the prior release.

When somebody complains that one of my legacy programs doesn’t run on this or that Microsoft piece of pooware, I respond, “That’s Microsoft’s problem, not mine”. I will eventually remove all of the Microsoft-specific stuff from my Web site.

(I did find a kind of VM (virtual machine) fix, at least for CELLAB—it’s described in a comment below.)

Fixing Chaos might be impossible, as it depends on a third-party “terminate-and-stay-resident” DOS-based graphics driver called Metashel. Conceivably Josh Gordon, who did most of the coding on the Chaos project, would have an opinion about the possiblity of a fix, but I don’t think I’ll bug Josh about it…it’s been nearly twenty years now since we wrote the Chaos ware. And I would imagine that Josh, being a hard-core programmer like John Walker, has moved on to Unix as well. Or entirely away from programming. At some point enough’s enough.

But just now I’m again in the mood for a taste of programming. Anything but start another novel!

Instead of rehabbing Chaos, I’m having a look at the Ultrafractal software which a lot of fractal fiends use these days. As a way of postponing getting back to writing, I’m implementing formulas for the extra fractals that I put into Chaos, such as the cubic Mandelbrot and the Rudy set…more on this in a later post.

The C source code for Boppers is online at the program’s home page, and I think that if someone were to recompile it with a modern compiler the executable probably would be okay in Windows 7. But, with Walker’s words in my head, I can’t really see rebuilding Boppers with the latest Microsoft compilers. In some sense it’s futile to keep upgrading my wares, as the operating systems are always moving on.

The good news on the bit-rot front is that my more recent program, Capow, still works in Windows 7. And the Pop game framework is fine, too.

One interesting side-effect of moving to 64 bit Windows 7. Apple iTunes performs so horribly and slowly on this platform that I finally cast off the irksome yoke by installing a patch called dopisp and removing iTunes from my machine. Dopisp acts as a plug-in for the (believe it or not) much faster and smoother (on my machine) Windows Media Player, and dopisp makes it possible to Synch the songs on my iPod… assuming you’ve converted your songs into the non-proprietary MP3 format (which can be done with iTunes or WMP). Free at last!

And I do want to keep the iPod…

March 28th, 2010 at 8:08 am

I’m glad that the surgery went well.

I love Thiebaud – The master of impasto, love that surface like frosting on a cake (which he is famous for painting, of course.) I’ve never understood why he isn’t held in even higher regard. Probably just the usual anti-California bias from the “real” art world in NYC.

I’m glad that the japanese toys are such an inspiration. I love looking at them while I work. The crazy color combinations, the shiny/opalescent/metallic surfaces, the weird sculpts – it’s a constant source of inspiration. Love to see Thiebaud paint some japanese toys, now that I think about it…

March 29th, 2010 at 3:55 am

I ran Cellab on Mac OS X 10.5 a year or so ago and it worked fine. (Using Wine)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wine_(software)

March 30th, 2010 at 7:12 am

I love the photos. Nice eye.

March 30th, 2010 at 7:55 am

“And I do want to keep the iPod…”

Try a player with GOOD sound quality and you will give up this final sad clinging to the Apple consumer cult…. 😉

March 30th, 2010 at 8:35 am

You’re hot.

March 30th, 2010 at 9:10 am

Awesome post. If you’re looking for a standalone object along with a web plug-in, have you considered Webkinz? They are the latest craze for any female child between the ages of 2 – 11.

I really kept looking for a description of what a chaldron actually is or looked like, but I think the point might be that we’re supposed to decide what it looks like.

March 30th, 2010 at 12:13 pm

Ed, what’s your idea of a good pocket MP3 player? I do like the iPod interface.

Thanks, Beth and AXH.

Sylvia, a chaldron looks kind of like a fancy blown-glass vase.

Re. getting my old program Boppers to run in Windows 7 without having to recompile it, I tried the Microsoft troubleshooter for older Windows programs that don’t run in Windows 7, and it’s no help.

Following along the lines Alex suggests, I learned that Windows 7 can in fact run a virtual machine in Windows XP mode, if you download and install some free Microsoft virtual PC software. I tried this just now, and it works pretty well. You get a little window on your screen which is an XP desktop.

CELLAB runs fine in the XP window—to make it easy to find your files, you drag the CELLAB folder from your normal C: drive (if that’s where it lives) onto the desktop of the XP Virtual machine window.

And inside there I can get Boppers to run—but with frequent crashes. And CHAOS doesn’t work in there at all.

(This is all in some way connected to Lethem’s playing with virtual worlds. Virtualization as a way of life. I’ll post more on this theme soon.)

But what about CHAOS? Today, I found I could implement my favortie two fractals in Ultrafractal, these being the Generalized Cubic Mandelbrot set and the Rudy Set. And Ultrafractal kicks butt in terms of speed. I’ll be talking about this more in a later post, sometime this week or next.

March 30th, 2010 at 10:37 pm

Hi Rudy, Nice blog you’ve got here. It’s been a long while since I’ve seen you, I will keep my eye on your blog. best, cindy lee b

March 31st, 2010 at 6:30 am

Rudy, have you seen XKCD today? A. Square is today’s guest . . .

The strip is inspired by a new 4D platform game called Miegakure!

August 1st, 2010 at 7:17 am

The chaldrons are a little more consistent if the displays people use for VR are holographic. Then the free-standing chaldrons are just the same chaldron .gifs (or copy-protected .gifs) or whatever running on separate displays. Like, you know, I’ve got a huge display on each surface of the VR room, and a separate display with just a chaldron, out in the hall.

Or to make it more boringly realistic, everybody’s got VR/ER eye implants, and the difference between a VR chaldron and a hallway chaldron is just whether you’re in total virtual vs. partial enhanced reality at the moment. I like the idea that something that confuses, intrigues, and troubles us as 2010 readers is just too boringly technical to explain in the book.

Or maybe the letdown was the point. I mean, I haven’t read the book but maybe he set you up with the expectation that they’re cool, but then he’s letting you know they weren’t really all that cool to start with, or the fascination wears off or the fad has passed. Maybe you’re supposed to wonder why you bought into the hype.

Oh yeah, your story of running Virtual PC (which is running the DOS emulator) inside Windows 7 reminds me of that Larry Niven story of the planet in a dual black-hole system that keeps getting wrapped in invisible layers of reality displacement or something. If you don’t get off before the next layer comes around, you get trapped. But you can visit your trapped friends with a sort of diving costume…just don’t stay too long…

August 23rd, 2010 at 5:34 pm

I assumed with all of wordplay in Lethem’s novel (Obstinate Dust/Infinite Jest being my fave) that a Chaldron was simply a cross between a chalice and a cauldron. The chalice being Apollonian, of light, Jesus, the grail, the cauldron the female darkness witchy and deep. The perfect most sought after blend of male and female, union, alchemy.

I’m a native New Yorker so elsewhere seems two dimensional to me.

November 10th, 2010 at 7:11 pm

The chaldron symbolism seemed to fit perfectly to me. I liked the book, thought it was a little strained at a couple of points, but the chaldron thing wasn’t one of them. Solid symbol on many levels (pun not intended but adopted after due consideration), well integrated with the player’s stories.

I absolutely disagree with your “two explanations” analysis. One or the other, or both? What are you talking about? They are expensive because people desire them. Virtual chaldrons to possess in the game are expensive because people desire them. 3d hologram chaldrons are commissioned because people desire them, and want to bring a piece of their fantasy world to their everyday surroundings. Wow, talk about being hit over the head with a symbolic hammer.

I don’t get the grail reference from Emily. Too superficialy deep.

January 27th, 2011 at 1:41 am

Rudy:

Just finished “Chronic City,” and am dealing with a faint discomfort at the thought of missing something integral to the story. I thought that the chaldrons were a good way for Lethem to bring up the VR phenomenon of people paying real money for intangible objects in a sim-world, (like people sometimes do for WOW characters, etc,) but beyond that I couldn’t see why the author made them so significant. So what if they’re symbolic? A symbol is only relevant to the extent that I, the reader, can grasp it, and this just felt like a weird shroom trip, non-essential to the plot. I also felt weighed down by the over-sharing and self-reflection. I’ve been unable to make it through one or two P. Dick stories for the same reason.

I get the feeling that the main character is in a constant state of “waking” from the illusion of the city. His role as a “Gnuppet” for this virtual world gets confused because of his association with “non-dupes” like Perkus and Oona. The closer he gets to the truth, the more distorted his reality becomes. There’s a lot of guilt in this character, which I think points towards his reluctant acceptance of the fake world. It seems like the stability of the real world is only gained by complying to the unspoken rules of the fake one (the mayor’s ending comment about the view from his apartment seems like a veiled threat once Insteadsman discovers it, the view, has shrunk)…but again, I do feel like I’m missing something. A very enjoyable book, even though it left me scratching my head.