[Back to memoir excerpts. Somehow the Sixties feel very close today!]

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, I was at Rutgers Univeristy learning math. For the first time in my life, I was taking courses that I found difficult in an interesting way: abstract algebra, real analysis, topology, and mathematical logic. And, for the first time since high school, I was attending all the class lectures and doing the homework.

[Boyhood suitcase of magic tricks.]

My wife, Sylvia, was finishing her Master’s degree in French literature. I liked hearing about the wild books she had to read, like medieval plays featuring Eve and Satan, or the poems of Apollinaire. In the evenings, she and I would do homework together in our little living room. It was cozy.

The Rutgers math department was giving me some financial support as a teaching assistant, and I met twice a week with a section of calculus students to show them how to do their homework problems—they got their lectures from a professor in a big hall. Working through the problems on the board, I finally began to understand calculus myself. It made a lot more sense than I’d realized before.

I was undergoing a constant cascade of mathematical revelation, even coming to understand such simple things as why we need zeroes, or why “borrowing” works when you’re doing subtraction. I was learning a new language, and everything was coming into focus.

The mathematical logic course was a particular revelation for me. I liked the notion of mathematics being a formal system of axioms that we made deductions from. And I reveled in the hieroglyphic conciseness of symbolic logic. From the academic point of view, I was beginning to see everything as a mathematical pattern. But in my personal life, everything was love.

Sylvia and I were enjoying the Sixties—we went to the big march on the Pentagon, we had psychedelic posters on our walls, we wore buffalo hide sandals, and we read Zap Comix. I smoked pot rolled in paper flavored like strawberries or wheat straw or bananas. Sylvia bought herself a sewing-machine and started making herself cool dresses.

At the same time, the war in Vietnam was casting a bitter pall. Those who didn’t live through those times tend not to understand how strongly the males of my generation were radicalized against the United States government. Our rulers wanted to send us off to die, and they called us cowards if we wouldn’t go. It broke my heart to see less-fortunate guys my age being slaughtered. My hair was shoulder-length by now, and occasionally strangers would scream at me from cars.

We were friends with a wild math grad student named Jim Carrig, from an Irish family in the Bronx. Jim and his wife, Fran, were huge Rolling Stones fans—they were always talking about the Stones and playing their records. They’d sign up early to get a shot at the tickets to the touring Stones shows. Thanks to them we saw the Stones play a wonderful afternoon show at Madison Square Garden.

“Did y’all get off school today?” asked Mick, strutting back and forth. “We did too.” And then they played “Midnight Rambler” and he whipped the stage with his belt—a trick we took to emulating at parties.

The Carrigs threw great Halloween parties. They lived an apartment on the second floor of a house, and Jim would stand at the head of the stairs like a bouncer, checking up on his guests’ attire. “Get the f*ck outta here!” he’d yell if anyone showed up without a costume. “Go on, we don’t wanna see you!”

I came to one party as a Non-Fascist Pig. That is, I bought some actual pig ears at the supermarket, punched holes in them, threaded a piece of string through them, and tied them onto my head. I lettered, “F*ck Nixon,” onto my T-shirt. I pinned on a five-pointed Lunchmeat Award of Excellence star that I’d cut from a slice of Lebanon bologna. And I carried a pig-trotter in my pocket to hold out if anyone wanted to shake hands with me.

When Sylvia and I went to see the left-wing movie Joe, the movie theater played the Star Spangled Banner before the film, and there was nearly a fight when a guy two rows ahead of us wouldn’t stand up. Turned out the guy was a Viet vet himself. “That’s why I went to fight,” the vet told the older man harassing him. “To keep this a free country. I don’t have to stand up for no goddamn song.”

I was very nearly drafted, undergoing a physical that classified me 1A. I’d thought that my missing spleen would earn me a medical exemption, but no dice. I still remember the medical officer who told me the bad news. Sidney W… oh, never mind his full name. He seemed to have a chip on his shoulder. Maybe he’d been drafted himself.

I bought some time by faking an asthma attack—and then they switched to a lottery number system for the draft, and I happened to get a comfortably low number. I wasn’t going to Vietnam after all. I was going to keep on learning math, being a newlywed, and having fun.

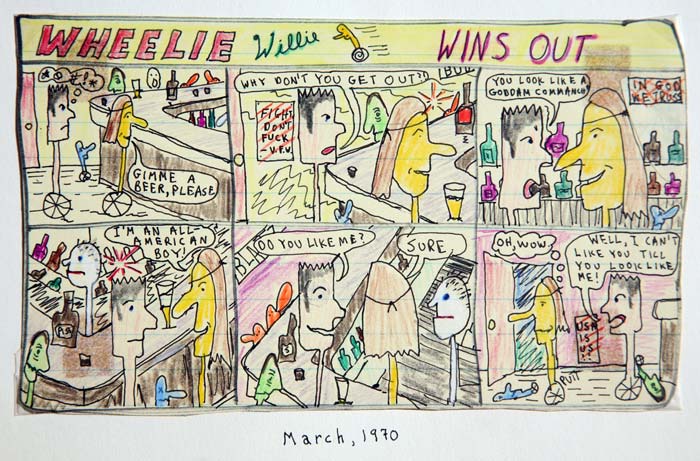

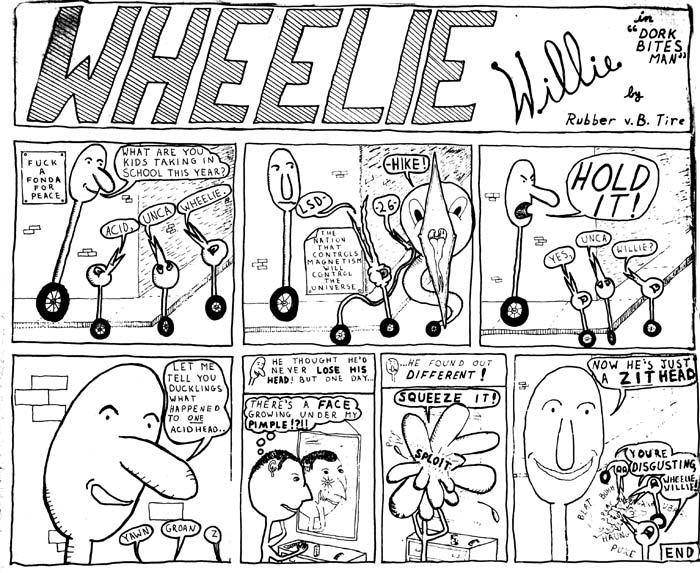

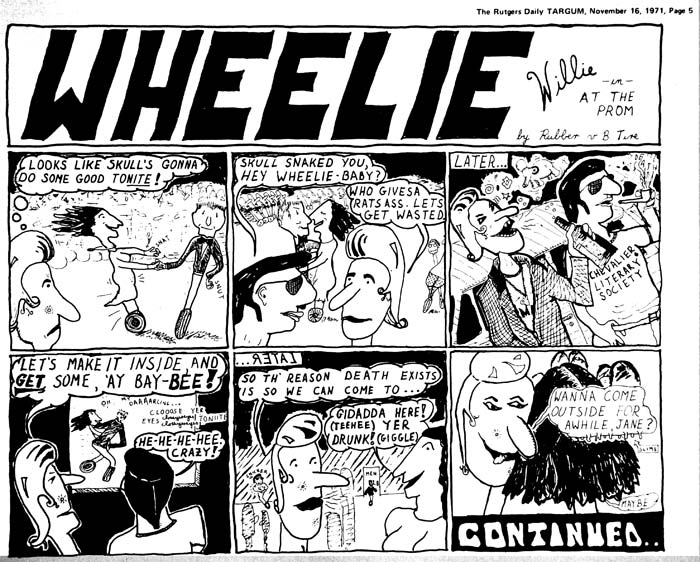

The tidal wave of underground comix inspired me to get some Rapidograph pens and to start drawing comics on my own. I developed a wacky, left-wing strip called Wheelie Willie that occasionally appeared in the Rutgers campus newspaper, the Targum.

I felt uneasy about my ability to draw arms and legs, so my character Wheelie Willie had a snake-like body that ended in a bicycle wheel. Some of the students must have liked the strip, as a fraternity once went so far as to have a Wheelie Willie party, not that I attended it.

Another close friend was my fellow math grad student Dave H. He was a skinny guy with an odd way of talking—he almost seemed like an old man. He always said “Rug-ters” instead of “Rutgers,” and “pregg-a-nit” instead of “pregnant.”

When Dave arrived for our grad student orientation session, he told me that he’d demonstrated against all three of the current presidential candidates: Humphrey, Nixon, and Wallace. And he’d been arrested in the Chicago convention riots. He was always going off to marches and demonstrations. Once he even roped Sylvia and me into making a trip to give support to the AWOL soldiers in the brig at Fort Dix. The soldiers gave us the finger.

November 7th, 2008 at 2:23 pm

Good stuff! Real homage to Carl Barks in the second one.

Yep, those were the days. Remember the ‘Draft Dodger Rag?’ “Sarge, I’m only eighteen, I got a ruptured spleen, and I always carry a purse; I got eyes like a bat, my feet are flat, my asthma’s getting worse. Think of my career, my sweetheart dear, my poor old invalid aunt; besides I ain’t no fool, I’m a-going to school and I’m workin’ in a de-fense plant.”

January 3rd, 2010 at 7:52 pm

Hi, Rudy, been reading your books & even playing with your fractal pgm over the years…here’s what i’m writing about…

I’m promoting my just published book “THE UNTOLD SIXTIES: When Hope Was Born,: subtitled “An Insider’s Sixties on an International Scale.” It provides an entirely new and authoritative view of this era. See:

http://language.home.sprynet.com/otherdex/sixties.htm