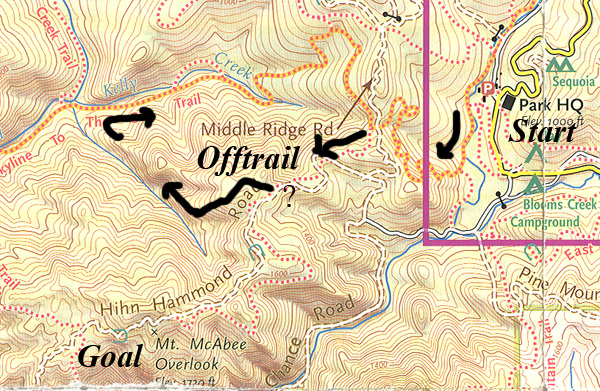

On Tuesday, Jan 23, 2007, I went for a big hike in the woods at Big Basin State Park, which is an hour-and-a-quarter’s drive from my house. I’d planned to walk up the so-called King Trail to the Mt. McAbee overlook, but I missed a turn or something and stemmed off into a smaller trail that dead-ended on an old logging road with trees across it blocking the way. I picked my way around the trees and kept going. At first I thought I was still on the right trail and that it was just poorly maintained. And then I realized I wasn’t on a trail at all, but I figured that as long as I headed uphill, I’d reach the top of Mt. McAbee all the same.

I was enjoying being in the wilderness, thinking about all the silp minds in the trees and leaves and air, and especially the genii loci or spirits of place that inhabit certain spots.

I’d been thinking of spirits of place from reading up on Papua New Guinea spirit boards, in which the natives hope to house some local spirits of place. Kind of like bird houses. As chance would have it, the other day I saw a documentary TV show about a tribe in a jungle, and it was raining too much, and an elder man said the rain was because the spirit of the sacred bend in the river was angry because people were disturbing him, and then we see the kids playing there and they say, “We like playing in the sacred bend of the river!” It was refreshing to see how children are just as ready to ignore elders’ injunctions when the tribe shares an animistic religion as when they’re kids in a Christian society. Somehow when we read about other society’s religions, we imagine every single one of “them” takes their religion very seriously and robotically—but in any society there are jokey, agnostic, practical-minded people who view religion as just another input in the mix.

Anyway, I’m walking along, and suddenly the spirits start harshing on me. I encounter a stand of tough-to-get-through manzanita, with branches like stern claws. I fight my way through, expecting to find a saddle ridge leading up to my targeted peak, but damn, there’s this really deep gorge here with a kind of scary slope to it.

Studying my map—finally really seeing it—I come to understand that the correct trail is way over on my left, passing along the high ground at the head of the canyon. I’m on a wrong (lower) peak, and the gorge is between me and my goal. The good news is that the gorge contains a blue line, which must be stream leading down to the Skyline to the Sea trail which itself wends along the bottom of Big Basin itself. I decide to blow off Mount McAbee and clamber down the slope into the gorge, follow the stream to the Skyline to the Sea trail and take that back up the basin to the park headquarters where I parked my car.

Heading downwards, more and more mental danger signals go off. The thick humus of leaves and sticks slips beneath my feet. Most of the branches I might grab onto are dead and brittle. Up ahead are some giant boulders with fairly sheer drops on their downhill sides. I focus, planning my route, which is something I’ve always enjoyed about tramping the woods and mountains—looking ahead and picking out the safest and easiest route. I’d be doing that a lot on this outing—to the point of getting sick of doing it.

The best route seems to lead over a boulder, and as I work my way down a spirit—that is a branch—plucks off my beloved, expensive, perfected-via-many-readjustment-trips-to-the-optician bifocals and sends them skittering down the slope, who knows how far. I can’t see! I do dig out my prescription shades form my knapsack, but it’s shady and dim in the gorge, so it’s hard to see through them. I search a half hour for my lost glasses with no success.

And now I’m at the woodsy bottom of the canyon. In retrospect—and I did a lot of retrospection in the next three hours—it would have been easier to go up the canyon and find the so-called King trail that I’d lost. But, seriously underestimating the distance to the Skyline to the Sea trail, I headed downstream.

On a good day, with my glasses and with the sun shining and with a walking stick (which I’d neglected to bring) and without time pressure (I’d gotten a rather late start, so I had nightfall to worry about), I would have found this little scramble to be exhilarating. As it was, the passage was a strenuous ordeal. And the walk back up the Skyline to Sea trail was hella long. It was quite dark when I finally made it back to my car—wet, bruised, exhausted, half-blind. I wore my shades to drive home, switching on the brights whenever the other lane was clear.

But it was a useful day. Even if it wasn’t exactly fun, I got some insights. For one thing, it’s always salutary for me to be reminded that I’m not in control. And for another, while I was struggling those miles along the steep, slippery banks of that rock-and-log-choked stream, I came to revise some of my notions about silps, spirits of place, and genii loci. Previously I’d been laboring under a lazy default happy-hippie conviction that Gaia is our friend, that nature is a nurturing mother. But in the wilderness I was reminded that, in truth, nature is utterly indifferent to us. Each object is placidly doing it’s own thing. They have no feelings towards me whatsoever. And the stark disinterest can feel like hostility.

I now see that if, for the purposes of my novel, I do want to ascribe minds and personal feelings to the spirits of place, then these elemental minds are just as likely to be hostile (stealing my glasses, making me slip), as opposed to being helpful (extending a solid branch for me to grab).

So rather than having the silps smiling and dancing around and helping Jayjay and Thuy build their house in the woods—I’d been thinking of an Amish barn-raising kind of vibe—maybe it’s more that the silps will be tripping them up, breaking their fingernails and being sure that nothing fits. Maybe the silps will like hostile xenophobic neighbors jeering at immigrants who are trying to fashion an ethnic little dwelling for themselves. A brick flies through the window, wrapped with a paper saying, “No Humans Here!” In other words, I’m seeing a scene where things go wrong for Thuy and Jayjay in the woods. And that’s fine, it’s more interesting that way for the story. One of the basic tricks for story-telling is to have the characters’ plans go awry.

Maybe tomorrow I’ll go back there early in the morning wearing my backup glasses and find those glasses that got away. Running as fast as their little legs would carry them…

January 26th, 2007 at 7:32 am

Some tree with a gnarly face in its bark is wearing those glasses right now. Too bad they weren’t teep-tagged . . .

January 26th, 2007 at 8:45 am

Wonderful post. It reminded me of Stephen King’s “The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon” – a very similar transformation of the nature of nature and what it means to be alone in an area that you’re also a part of – we’re natural, but something sets us apart from nature. I don’t know if it’s a blessing or a curse, assuming it has to be one or the other.

Good luck with finding the glasses. It’d be an excellent postscript if they turn up.

January 26th, 2007 at 11:40 am

Been there and done that. Scary.

Actually I got lost without a map. But I had my dog. So when I began to get worried I put the dog on the leash, and then I led her and me around in more circles. I should have said, “Find the car, baby”. But she relied on me and never questioned my circles.

When I finally did get to the car with darkness near – I was joyfull. I think the dog thought it had been fun though.

I suppose in a way it is good to get lost. New thoughts break through.

January 27th, 2007 at 11:38 pm

on a considerably lighter note…. in perhaps the same way a weiner dog (dachsund dog) is naturally attracted to old world klezmer music rather than BlackSabbath or disco, an amazing and far-fetched enlightenment suggests that the squirrels at Glacier National Park prefer the french debonaire Maurice Chevallier….