I had a dream where I went to the future and met a guy who wants to be an SF writer. He describes a story idea: a guy writes an SF story that turns out to be about an actual person in the future. And in the dream, I’m kind of dizzy, sorting that out. Am I the guy in his story? Or is he the guy in my story?

Tourists waiting to see Old Faithful go off. We ate hamburgers in Great Falls, Montana. I hadn’t had a burger in maybe seven years. I felt like I was taking some unknown drug. Fearful of the coming effects.

Mostly Yellowstone was crowded, but the first night we were there at 8 PM and had the geysers to ourselves. Fellini-esque, another world.

Scenes like you see in the old school landscape paintings. Lower Yosemite Falls.

Sweet abandoned Montana farms.

The pulsing bifurcating waterfall above Avalanche Lake resembles the graph of the logistic map. If a cascade was intelligent, would it move the rocks around more?

Note that with lazy eight, as planned for Postsingular all these objects and processes can “see.” If water was intelligent, would floods be worse? Would leaves wave more extravagantly? Smart fires might be harder to control, more prone to leaping across a gap to the next dry branch. But fire lacks effectors, no? A tree has slow effectors in its growth. And possibly it can vasodilate to affect the flexibility of its branches. But fire I think is passive.

The parks and the West in general are full of motorcyclists.

At Yellowstone outside a park grocery I overhear a careworn, weathered biker talking to a woman just off her shift. Such a hard life this man must have had, he looks almost like a bum. She’s Roxanne, he’s Wild Bill, “though you might better call me Mild Bill.” He pulls a two inch cigar stub out of his layers of clothes and chews it ready to light up. “Didn’t mean to scare you off. Just kidding.” He gets on his bike and circles around the parking lot before leaving, wobbly and alone.

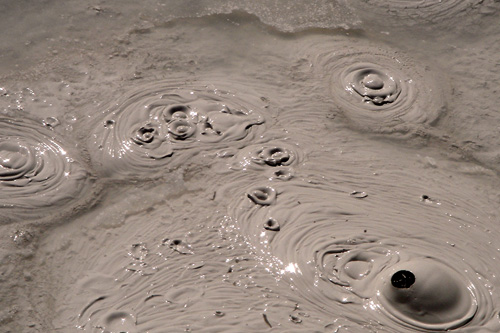

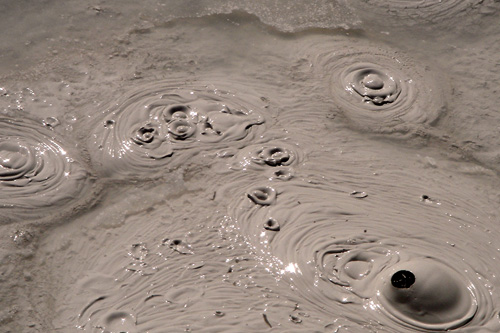

We visit some boiling mud pots at Yellowstone. Plorp. The bubbles throw of small gobbets of hot mud, the gobbet occasionally forming a tiny bubble of its own. The gobbet could be our universe. Yes, this is how the world arose.

We listened to the Allman Brothers song “Ramblin’ Man” a lot. I love the part at the end when the one guitarist repeats the same little ostinato figure ten twenty thirty times — he can’t stop — and the other guitarist plays a single long note soaring out of that, rising up, dying down.

I’ve never used the name “Robert” in a book. The micro-orgainisms in geyser run-off distribute themselves by temperature. The high-hot-loving guys plate up iron on themselves and get red. The medium-hot-loving guys have chlorplasts and are green.

Driving down a 13 mile dirt road to a campground in Lewis and Clark forest. Car covered with dust. Two hand prints emerged on the side. “The Miracle of the Hands.” An angel pushed on the car to keep us from going over the edge.

Hiking from Logan Pass toward Mount Reynolds in Glacier National Park. I was walking the spine of the Continental Divide. I look over at Mount Reynolds, this huge single rock. Such a mass of rock and quanta.

What is reality? I have a rush of ontological wonder sickness. Why does anything exist?

At a rare check-in at an open computer, I got a nice email from Seth Lloyd regarding my review of his book Programming the Universe. He said, “I understand that you're not fond of quantum mechanics; but hey, that's the way the world works!” Maybe he’s right. But now, staring at the mountain, overwhelmed by its brute physicality, I can’t quite remember the details of what Seth said in his book. This is the outcome of, huh, a random algorithm, huh? Hit don’t feel that way.

The ubiquity of the same forms: trees, dendrites, clouds, mountains, animals, my thoughts. All standard patterns that nature loves to grow.

I threw a raisin to a pika (a rodent like a marmot or ground-hog or squirrel) and it got the raisin and wanted to eat it, but was uneasy at still being fairly close to me, but wanted to bite into the delicious raisin right away, so, torn by the opposing drives, the pika let out this gorgeous shrill liquid squeek. I could listen to that sound all day.

We visited Hemingway’s grave in Ketchum, Idaho. It was in a small, ordinary graveyard by a busy road into town. Looking for it was a replay of looking for my father’s grave in Herndon, Virginia, in July. In both cases I asked a Mexican guy who was mowing the lawn, and he didn’t speak English. My father had a white beard and he liked it when people said he looked like Hemingway. I found Hemingway’s slab, seven feet long, flat on the ground between two pines. For some reason people leave coins on the slab. Idiots. I cleaned off the letters of his name, blowing away the pine needles, shoving aside the coins. I saw his ghost. He said a lot of people came there looking for him, too many, but he was gonna say hi to me since I’m a writer.

Hem was about the first writer I really “got” and admired, back in high school. I liked his conciseness, his haiku-like clarity. All the stuff about moral codes and being a man, that’s all pretty much rotted away, though. F*ck the code. You have adventures, is all. Life is a wonderful adventure. I do have a code, I guess. But it seems so teenage to formulate it.

On the other hand, Hemingway was in the war, he saw people getting killed, so give him some slack on that.

In Missoula, Montana, I read a review of Scanner Darkly in a local free paper, The Independent. Written by, like, a college kid. And he’s chiding the director Linklater for making a “Just say ‘No’” movie. He doesn’t realize that was Phil’s rap in the book as well. That drugs are bad for you. I remember people having that reaction when the book came out. Like, Phil is being a kill joy. But he earned his right to be anti-drug. He went all the way in, deeper than a partying college kid can imagine. And — Phil was so cool — he saw the experience as darkly comic the whole way. Like Hemingway and war. Drugs our version of war.

What would my own code be?

See the gnarl, know the divine, love those around you.

I rent a mountain bike to ride down Mount Baldy. Drop 4,000 feet in 10 miles of single-track trail. It’s harder than I expected, I can’t look away from the path for even a second, or I’m likely to run off the edge. It uses every iota of mountain-biking skill that I’ve gained in the last twenty years of riding my bicycle. The boy who rented me the bike said the ride would be “easy.” I wanted it to feel like skiing, the way biking sometimes does, and now and then it did, but the required focus of attention was much more than I’d expected.

Hemingway liked to ski. He didn’t know about mountain biking like this. Or about parasailing. Imagine coming back in fifty more years, all the further new sports that’ll have emerged.

To be continued…