In Mathematicians in Love I’m working on a scene were my characters surf through a tunnel to a parallel sheet of space.

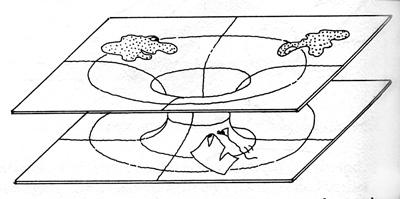

I first thought about how to do this in Chapter Eight of my 1984 book, The Fourth Dimension. The traditional way for connecting two parallel sheets of space is to imagine a hump that bulges out from one space and merges into the other space as shown in the figure below, which was drawn from one of my sketches by David Povilaitis. This kind of connection is traditionally known as an Einstein-Rosen bridge or a wormhole.

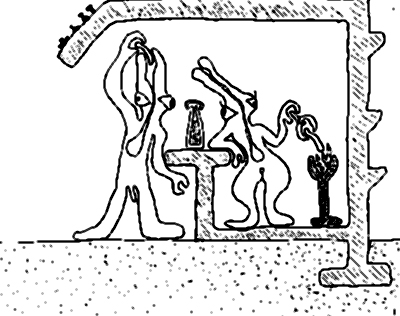

In this scene, by the way, we see the traditional Edwin Abbott Flatland hero A Square about to sneak off into the parallel world of Globland with a married Flatlander woman Una, whom he hopes to seduce. Note that “A” is not an abbreviation, it’s his full first name. (The science writer Ian Stewart recently published an interesting Annotated Flatland as well.)

Although we often think of Flatland as being a two-dimensional world like a table-top, we can also imagine, with Charles Howard Hinton and Kee Dewdney, a 2D world that’s turned upon its edge — like a cross-sectional slice of our planet.

By the way, I once edited a collection of Hinton’s writings called Speculations on the Fourth Dimension which is now out of print, but available used, or (in part) online.

In the Hinton/Dewdney-style 2D world we have a notion of up/down matching the familiar one. In my 2002 novel Spaceland I used this kind of image.

In this picture we see a couple of Flatlanders at a hot-dog stand. They’re drawn with some internal detail instead of just as, like, lines and squares with eyes. Those bumps on the roof are Flatland writing.

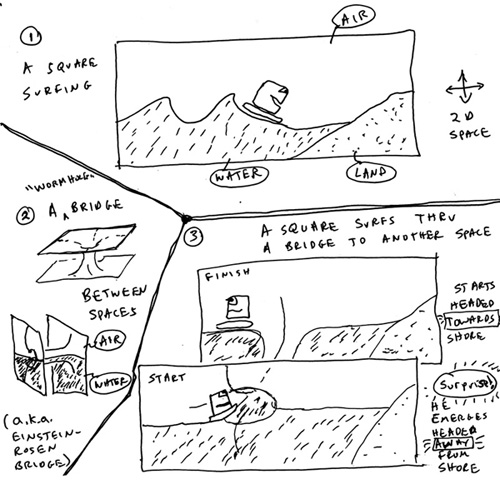

Now we get to the new image for today.

This is a three-in-one picture:

(1) A Square on a surfboard in a 2D world, riding a wave towards the shore.

(2) A couple of sketches of an Einstein-Rosen bridge between two parallel universes, and in one of them I’ve drawn in water and air for the two worlds. The water sloshes right through the tunnel.

(3) A Square surfs into one end of an Einstein-Rosen bridge and comes out the other end — now facing away from the shore.

Before drawing this picture I hadn’t realized that the passage through the hypertunnel would turn my surfers away from the shore. That’s why I love math and logic. You set up the system, turn the crank, and, if you’re lucky, you learn something new. It’s like logic is a complicated feeler that we use to reach out and touch invisible part of the mental world. As Kurt G�del once told me, “The a priori is very powerful.”